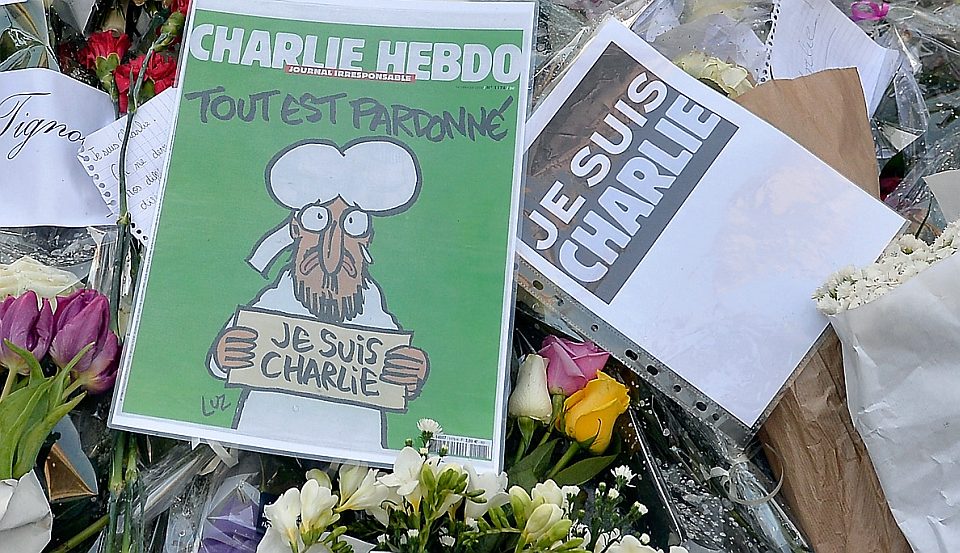

Je suis Charlie? I’m sorry, but that’s no longer enough

‘Je suis Charlie’ has become a dogma, harming the fight for free speech.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

This week, nearly four months after the massacre at Charlie Hebdo, it’s become clear that there are two profoundly problematic responses to that French mag and its bloody travails.

The first is the cowardice of the Western writers and cartoonists who cannot bring themselves to say ‘Je suis Charlie’, at least not without adding a massive ‘But’ at the end: ‘But it was a racist magazine’, ‘But it upset Muslims’. And the second unhelpful response comes from those who can only say ‘Je suis Charlie’. Those who have turned ‘being Charlie’ into the litmus test of liberalism, the passport into polite society, the measure of every man and woman’s moral decency. The reason this second response, the ‘Charlie’ camp itself, is becoming a problem is because it is obscuring the bigger, historic, Europe-wide crisis of freedom of speech, which goes far beyond two psychotic gunmen acting on behalf of Allah. In fact, it has become a means of avoiding talking about that crisis. ‘Je suis Charlie’ is increasingly a distraction, and a dangerous one.

One thing that most people who are in possession of a moral compass will agree on is that writers like Peter Carey are moral invertebrates. This week, Carey and other prominent authors — Michael Ondaatje, Teju Cole, Rachel Kushner, Francine Prose — said they were pulling out of a PEN gala dinner in New York following PEN’s decision to give its Freedom of Expression Courage Award to Charlie Hebdo. They feel that giving this award to a rabble-rousing mag like Charlie is ‘inappropriate’ – that dead bureaucratic phrase used by 21st-century cowards and censors who can’t bring themselves to say ‘heretical’, which is what they really mean.

Kushner said she didn’t want to celebrate a magazine that promotes ‘cultural intolerance’. Carey says: ‘A hideous crime was committed, but was it a freedom-of-speech issue for PEN America…?’ When you’re adding a ‘but’ right after talking about the cold-blooded execution of 12 people for the crime of having made fun of a religion, you know you have problems. Carey went on to slam the ‘cultural arrogance of the French nation’, which ‘does not recognise its moral obligation to a large and disempowered segment of their population’. The fantastic irony here is that Carey is himself being culturally arrogant, depicting an entire nation as a gaggle of racially unaware ignoramuses: national chauvinism disguised as concern for Muslims. But the most telling thing is his idea that Charlie Hebdo should have wound its neck in rather than offend a ‘segment of the population’.

This cuts to the heart of the supineness of those who balk at any honouring of Charlie Hebdo, which includes not only those gala-flouncing writers but also Garry Trudeau, creator of the Doonesbury cartoon. The motor of their moral cowardice is the idea that we should avoid giving offence, that to offend is tantamount to abuse. Their elitist allergy to saying ‘Je suis Charlie’ reveals the extent to which the ideology of multiculturalism, with its relativistic notion that all cultures are equally valid and its instinct to shush criticism of any particular culture, has much of the literary set in its grip. Their description of ridicule and blasphemy — which is what Charlie did — as ‘cultural intolerance’ confirms the creeping criminalisation of certain forms of speech, the transformation of heatedness, controversy itself, into a social problem, possibly even a form of violence. They’re expressing one of the worst ideas of our time: that respect for an individual’s or a group’s sensitivities should trump the right of others to say what they want; that feelings are more important than freedom. Their ‘erms’ and ‘ahhs’ and ‘buts’ in relation to Charlie Hebdo add up to an alarming failure to stand up for freedom of speech; worse, they contribute to an increasingly chilling climate of word-watching and self-censorship for fear of giving offence.

It’s terrible stuff, yes. But is the response to such Charlie-dodging writers any better? Not really. There’s something wrong in the other camp, too, among those who say ‘Je suis Charlie’ all the time, and in fact have made ‘Je suis Charlie’ into a cultural signifier, a kind of password that grants you access to the Real Liberal Set. These true liberals, as they imagine themselves, have fetishised Charlie, turning what ought to be a liberal cry — ‘I support the right of everyone, including Charlie Hebdo, to say whatever they want’ — into a kind of dogma: ‘Je suis Charlie, and woe betide anyone who isn’t.’ The reason they have done this is as obvious as it is depressing: it’s because ‘being Charlie’, being opposed to the killing of journalists, is easy, far easier than digging down and trying to understand, not to mention oppose, the everyday, continent-wide undermining of freedom of speech and the way it is truncating what may be thought and said in almost every area of life today.

There is a certain kind of commentator – the self-styled true liberal – who only becomes animated about free speech when Charlie is involved. So they went into overdrive when Trudeau made his Charlie criticisms. They kicked up a fuss when Queen’s University in Belfast, citing ‘security concerns’, cancelled a conference on Charlie Hebdo. They went into meltdown this week over Carey, Kushner and the other backbone-free writers. But where were they when Dieudonne, the racist French comedian, was arrested for anti-Semitic speech? Or when a 24-year-old football fan in Scotland was jailed for singing an offensive song? Or when three homophobes in France were arrested for tweeting? Or during any of the other too-numerous-to-mention assaults on freedom of speech that have occurred in Europe in the nearly four months since the Charlie massacre? To be Charlie without also being Dieudonne, Rangers fans, homophobes, racists, mad tweeters and all the rest is not to be in favour of free speech at all — it is just to be Charlie, nothing more.

It’s not hard to see why these ‘true liberals’ are so drawn to the Charlie cause. First there’s the easiness of it (‘I am for the dead’, says one writer, which brought to mind that old campaign group Mothers Against Murder and Aggression — who, precisely, is for those things?). And secondly, the Charlie killings allow them to dramatise the crisis of free speech, to treat the assault on this freedom as an urgent, explosive, external threat, emanating from strange people polluted with non-European ideas and ugly intolerance. It is far harder to look at the true threat to free speech today, which comes right from the heart of our own societies, which is a product of the modern West’s own slow-motion abandonment of Enlightenment values and its everyday, drip-drip, not-especially-dramatic burying of the ideals upon which it was founded. How much more straightforward, and fun, to say ‘I oppose those two lunatics with guns’ than to look into the soul of your own society and see what a parlous state it is in — a result, not of one-off massacres or foreign influence, but of Western institutions’ own loss of faith in themselves.

For these ‘true liberals’ to turn ‘Je suis Charlie’ into a dogma is pretty disgraceful, because the key creator of our stifling, choking new era of offence-taking and controversy-policing has been liberal complacency, the silence over the past 30 years of precisely the kind of people now turning ‘Je suis Charlie’ into a measuring stick of morality. It was their failure to stand up convincingly to the introduction of hate-speech laws, and to criticise the censorious aspects of multiculturalism, and to challenge the reduction of the great ideal of tolerance to non-judgemental relativism, and to oppose all the formal and informal demands for censure we have seen in recent years, against everyone from racist bigots to Armenian genocide deniers to Dapper goddamn Laughs, which allowed the emergence of a climate in which more and more people, including the Charlie killers, believe they have a right not to be offended.

‘Je suis Charlie’ is too little, and it’s lethally too late. For the climate of punishing offensiveness has already been created, and it will continue to thrive so long as those who fancy themselves as true liberals draw everyone’s attention towards Charlie and Charlie alone, and away from the mundane suicide of Western values, expressed everywhere from new laws to Twittermobs to the death of free thought on campus. You’re opposed to the massacre of journalists at their desks? Congratulations, you aren’t a psychopath. What else you got?

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.