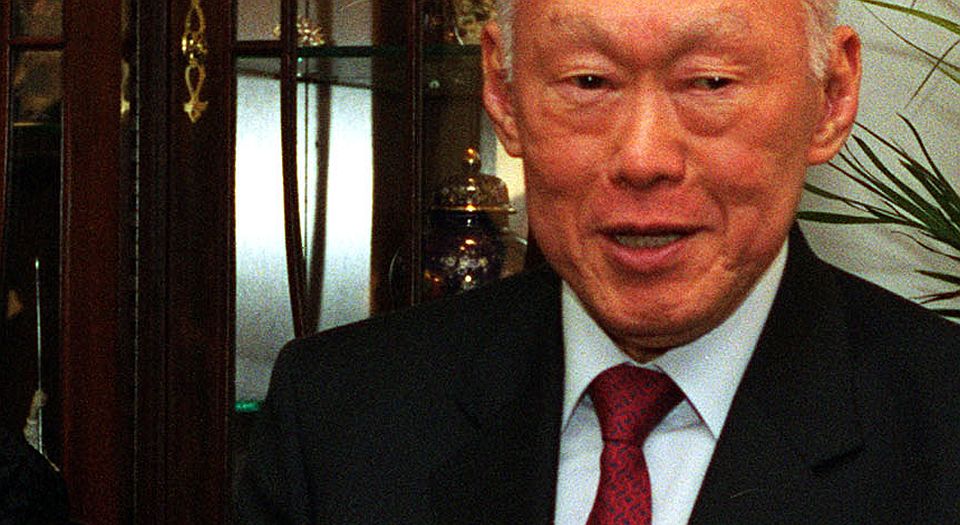

The Communist who made Singapore a capitalist success

Lee Kuan Yew transformed a small trading post – but at a cost.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

When my father-in-law was sent on his national service to fight the Communist insurgency in Malaya, he was given photos of the men he had to look out for. In the pack was Chin Peng, the leader of the Communist Party of Malaya – though before he rose against the British he had marched in the Victory Parade in London and been cheered for fighting the Japanese. The other dangerous insurgent was Lee Kuan Yew, a Communist and labour agitator in Singapore. Lee died this week, at the age of 91. He is not remembered as a Communist, but as the man who made Singapore a capitalist success story.

The main island of Singapore is just 26 miles wide and sits between the Malay Peninsula to the north and Indonesia to the south. It has a population of five-and-a-half million, and a Gross Domestic Product of $298 billion – thirty-sixth in the world, above Ireland and Portugal – and a GDP per head that is higher than the US.

From the nineteenth century, ethnic Chinese who struggled to prosper under the Empress Dowager’s regime had spread across East Asia, often as traders to more settled populations. City-states like Hong Kong, Macao and Singapore prospered as trading posts, with the expatriate Chinese playing a major role. Politically they were ruled by Europeans: offshore colonies that controlled trade among the relatively underdeveloped mainland Empires in China, Java and Malaya.

The rise of nationalism, first and foremost Chinese and Japanese nationalism, transformed East Asia. The Japanese overthrew the British colonies, and also fought with Chinese Kuomintang and Communist forces. The ruling elites that would come to power in Indonesia and Malaya were mostly graduates of the Japanese imperial schools for local officials.

The great Chinese diaspora in East Asia, of which both Lee Kuan Yew and Chin Peng were a part, were politically on the left, radical anti-imperialists inspired by Mao Tse Tung’s victories. In their own positions, though, they were mostly small traders, serving larger farming populations. In Singapore, the radicals were organised as the People’s Action Party, of which Lee Kuan Yew was a leader. Chin Peng’s Communist Party of Malaya was fighting Britain just to the north. And to the south, Sukarno and Mohammed Hatta were leading the fight for Indonesia’s independence from Holland.

These movements combined nationalist and socialist ideologies in a struggle against imperialism. They won through, forging independent nations that would shape East Asia and the world. But in all three countries, the nationalist leaders won the acceptance of the new power in the world, the US, by turning on the Communists.

The greatest slaughters were in Indonesia, where the Communist Party was more than a million strong. The conservative leaders in Malaya isolated Chin Peng’s Communists, who, though mostly urban Chinese, withdrew into the forests to fight a tenacious but doomed guerrilla war. Lee Kuan Yew turned on the Communists in Singapore, first forcing them out of the People’s Action Party, and then, in government, repressing them.

It is true that the Communists were set on seizing power, and just how progressive their rule might have been can be guessed at from the example of the People’s Republic of China. Nonetheless, the anti-Communist repression in East Asia was the rationale for a fierce assault on radicalism and an entrenchment of elite rule. As Lee wrote: ‘Could we have defeated them if we had allowed them habeas corpus and abjured the powers of detention without trial? I doubt it.’ (1)

Consolidating an independent capitalist state in the South China Sea had other problems. Despite the challenge the People’s Action Party posed to British rule, Lee was critical of the British policy of withdrawing from East of Suez. His island state was faced by much greater powers from the north and south. The initial solidarity of the struggle against imperialism collapsed. A proposed Malaysia federation of Malaya and Singapore failed because of Malay distrust of ethnic Chinese seizing power from the majority Malay population. Indonesia’s harsher climate, too, led to anti-Chinese feeling, and a trade war against Singapore.

Up to that point, Singapore’s success had come as a trading post for goods farmed and made on the larger mainlands of Indonesia and Malaya, but these two states turned instead to economic nationalism and protection, to cut out the Singaporean middle man. Lee’s substantial struggle from 1965 onwards was to rebuild Singapore as an industrial and financial base, not just a trading post.

There is no doubt that Singapore’s success is backed up by some vicious – and some just comical – measures of repression. Political opposition was barely tolerated for much of the Cold War period. There is also no doubt that the clampdown was demanded by Lee’s supporters in the developed West. Dr Albert Winsemius of the United Nations Technical Assistance Board advised that to get the investment needed, Singapore had to ‘get rid of the Communists’. ‘How you get rid of them does not interest me as an economist’, he said, ‘but get them out of the government, get them out of the unions, get them off the streets’ (2).

Still, the economic success story was remarkable and has led to the highest standard of living in the region, among the highest in the world. In his book From Third World to First, Lee gave a good account of how Singapore welcomed foreign capital to boost its economy, and adopted a pointedly pro-Western approach. He must be the only head of state ever to take a sabbatical to study at the Harvard Business School. The postwar expansion of the East Asian market due to the reconstruction of Japan, and the rapid industrialisation of South Korea, largely under the pressure of US military demand, meant that there was an expanding market for Singapore-based production. Lee offered Singapore as ‘a base camp for entrepreneurs, engineers, managers and other professionals who want to do business in the region’ (3).

Lee took advantage of the growing importance of China to further leverage Singapore, and establish independence from the US. Chinese leaders Zhao Ziyang and Deng Xiaoping both sought advice on the liberalisation policies in the region. His grip on power lasted longer than was wise, serving as prime minister from 1959 to 1990, and then in the advisory roles invented for him — ‘senior minister’ (1990-2004) and ‘minister mentor’ (2004-2011) — before retiring.

James Heartfield is a writer and researcher. His latest book, The European Union and the End of Politics, published by ZER0 Books.

Picture: Wikimedia Commons

(1) From Third World to First, by Lee Kuan Yew, Harper Collins, 2000, p 112; see also Muck Silk and Socialism, by John Platts-Mills, London, 2002, p387

(2) Singapore: Struggle for Success, by John Drysdale, Times Books, 1996, p252

(3) From From Third World to First, by Lee Kuan Yew, Harper Collins, 2000, p58

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.