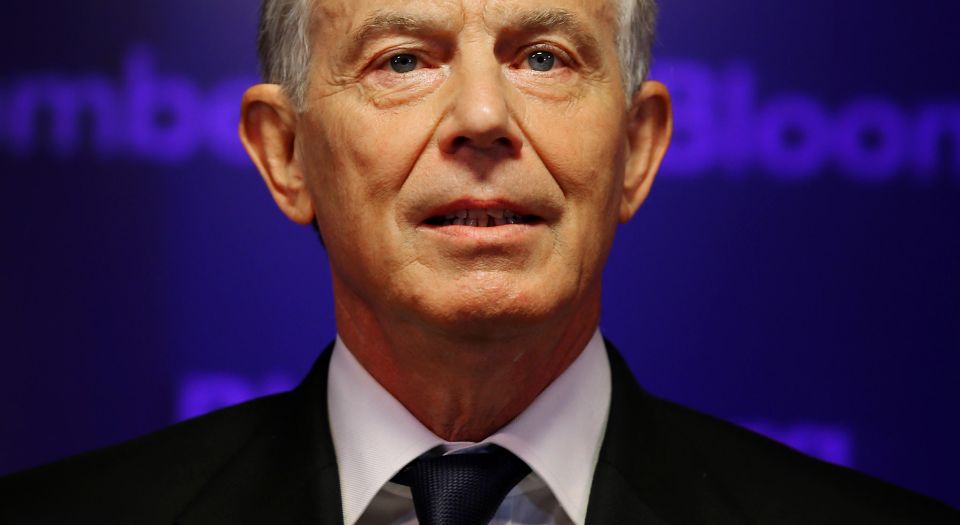

Blair: the whipping boy of ideas-lite Labourites

Bereft of vision, Miliband now cynically sells himself as Not Blair.

Tony Blair, the permatanned ghost of Labour victories past, continues to haunt British politics. Which is odd when you think about it. He resigned as prime minister and Labour leader nearly eight years ago and, since then, Britain has enjoyed two different prime ministers, and Labour two different leaders. But from news of his imminent removal from the UN-backed position of Middle East envoy to tales of his Lynx-like effect on Rupert Murdoch’s wife Wendi Deng, there Blair is, still making the headlines, still generating the column inches, and still fuelling shockingly unrevelatory books. (The latest is called Blair Inc: The Man Behind the Mask, which reveals that the man behind the Tony Blair mask is a really rich Tony Blair.)

But it is among the Labourite that the obsession with Blair is at its most potent. He is the fart in leader Ed Miliband’s party-political elevator, the whiff of the recent past that Labour and its media champions seem constantly to be trying to waft down the corridor. Take the story of Blair’s pre-General Election donation of £1,000 to each of Labour’s 106 target-seat candidates. Months before Blair’s hand even ventured towards his pockets, the rumours that he was donating had already prompted much handwringing on the Labour-supporting left. And when Blair did dig deep earlier this month, several candidates announced they would be refusing Blair’s money. In other words, the most electorally successful Labour leader in history, the man who led the party for over 10 years, has been dismissed as a dodgy donor – by his own party.

What is it about Blair that seems to prompt such a reaction from Labour and its supporters? Some argue that it’s because of what he has done since he left parliament in 2007. He’s fraternised with, and provided ‘consultancy’ services for, dubious world leaders, such as Kazakhstan president Nursultan Nazarbayev, and he’s grown even more filthy rich in the process. He’s a corrupted figure, they say. But even that doesn’t quite make sense. Yes, Blair has made millions, but he has also given millions away as part of his philanthropic work. And, besides, other recent prime ministers, such as Ted Heath, Margaret Thatcher, John Major and even that penny-pinching Presbyterian Gordon Brown, all enjoyed, or are enjoying, similarly lucrative post-political careers, but with none of the opprobrium.

With Blair, it’s different. It’s not what he has done since 2007 that explains the antagonistic focus on him. In a sense, it’s not what he did before 2007 that explains it, either. Rather, the problem with Blair lies with what he represents. He is a symbol of New Labour. He is the rictus-grinning, sound-bited and booted apotheosis of everything that is wrong with modern party politics, ‘a toxic influence on the body politic’, as one Guardian columnist called him. And, most important of all, he is therefore everything that the current rendition of Labour according to Ed Miliband is striving to negate. Where Blair was polished, Miliband is still trying to eat a bacon sandwich; where Blair was at ease with credit-fuelled capitalism, Miliband is full of deathly platitudes about inequality and the cost-of-living crisis; and where Blair just loved a good old liberal-interventionist tear-up in places like, well, Iraq, Miliband is a little more reluctant, as he showed to much Labourite fanfare when opposing intervention in Syria in 2013 (but failed to show when happily approving intervention in Libya in 2011).

Of course, the differences in substance between New Labour and New New Labour are hard to discern. But that’s where Blair, as the wild-eyed embodiment of New Labour, actually comes in useful. Transformed into everything that was wrong, and went wrong, during the 2000s, from Iraq to the existence of super-rich people, Blair provides Miliband’s Labour with a means to affirm itself, a means to define itself, a means to give itself some semblance of purpose. And this is why Blair hangs around Labour like a bad smell; Miliband and Co need him. That’s right: Blair is absolutely essential to the Labour Party today, not as a sugar daddy, or an inspiration to the party faithful to be wheeled on to stage during conference season, but as the best way for Labour to say what it stands for – albeit by saying what it does not stand for. ‘We are not New Labour.’

Miliband made this clear in his first interview after becoming Labour leader in 2010: ‘The era of New Labour has passed. A new generation has taken over.’ And it is this constant process of negating New Labour that has allowed New New Labour to imagine that it stands for something. Disavowing Tony is now one of Labour-supporting commentators’ favourite pastimes. As one put it: ‘[Blair’s] influence is certainly “very firmly felt” among his adoring Tory fans, as they build on the foundations he laid. But Labour’s leaders would be best advised to leave the swooning to Cameron’s acolytes.’ Blair is now the necessary evil to be forever exorcised in Labour’s midst, the scapegoat to be repeatedly sacrificed in order that Labour might ‘go again’.

Labour is not alone in this curious determination to wage an existential war on party-political traditions past. Ever since the then Tory chairman, Theresa May, told Tory supporters, ‘You know what some people call us: the nasty party’, ridding the Conservative Party of its ‘nasty’ image, cleansing it of ideological toxins, disavowing its socially conservative past, has become the closest thing Cameron et al have ever had to a mission. In the absence of something positive to stand for, some vision of how things ought to be, modernisation, the process of constantly bringing the party up to date through the jettisoning of what it once was, has become an objective. Gay-marriage supporting, feminist-loving and a sucker for female bishops – this is the Tory Party of today. No wonder ex-Tory prime minister John Major said that traditional Conservatives like himself felt ‘bewildered’ and ‘unsettled’ by contemporary Conservative policies.

But here’s the twist to this tale of party-political creative destruction. This constant disavowal of the past, this aggressive war on a party’s own history, pursued so relentlessly by New New Labour and the Tories, is actually the essence of New Labour itself. This really was the great talent of Blair and the fellow architects of New Labour. They seized upon the depoliticisation of party politics, the Labour Party’s decomposition, its hollowing out, and accelerated it, excising Clause 4 along the way – and, by doing so, they were better able to present Labour to the electorate as a marketer might present a product to consumers. As something new, modern, bang-up-to-date.

UKIP leader Nigel Farage loves to call Labour and the Tories ‘legacy’ parties. It’s a funny line, but it misses what is vital about these two deracinated political bodies: they are the anti-legacy parties. They are defined by a ceaseless anti-traditionalism, a restless hankering after the new through the rejection of the old. And right now, for Labour, Blair is very, very old.

Tim Black is deputy editor of spiked.

Picture by: Peter Macdiarmid/Getty

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.