Waiting for Chilcot

Why politicians and pundits are so desperate to see the Iraq War report.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

So, six years after Sir John Chilcot and his team began an independent inquiry into ‘the run-up to the Iraq War and its aftermath’ – ‘to establish, as accurately as possible, what happened and to identify the lessons that can be learned’ – the publication of their report is to be delayed. Again.

It could be the play for our politically clueless times: ‘Waiting for Chilcot.’ Nothing happens, no report arrives, no report goes, it’s awful. And yet, our political and media classes continue to wait. And wait they do in ever-increasing desperation and hope that perhaps, just perhaps, Chilcot and his report turns up — to provide meaning, to provide a reason for all of, well, this, for everything.

If that sounds like hyperbole, just listen to the way in which politicians and pundits are now talking about the Chilcot report. ‘[It is] so important to the country’s future’, said deputy prime minister Nick Clegg. ‘It’s time for the truth: it’s time to publish the Chilcot Inquiry’, said a Lib Dem councillor. ‘Immensely frustrated’, said prime minister David Cameron of the delay in the publication of the report. Its permanently postponed publication is like ‘a mirage for people seeking water in a desert’, remarked a commentator.

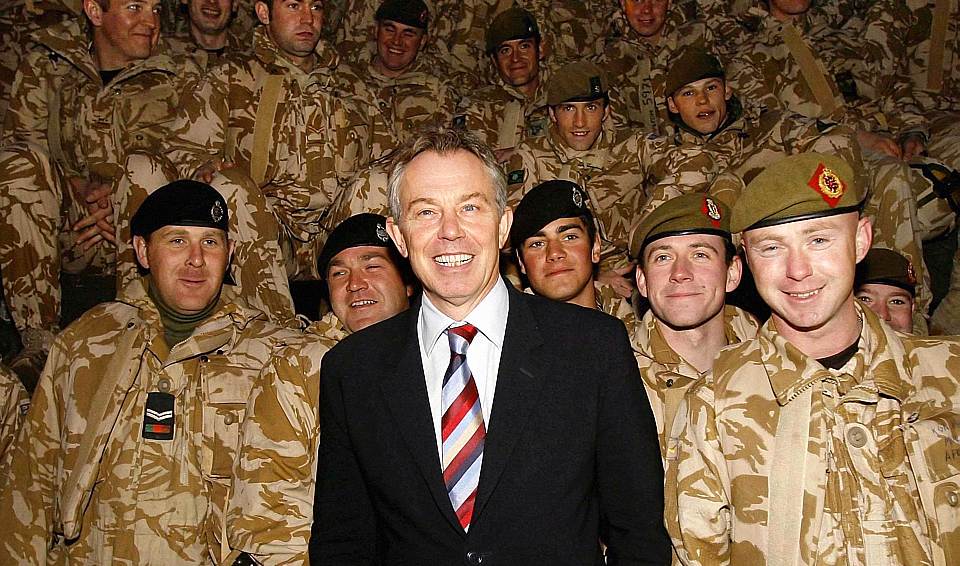

No doubt there’s cynicism nestling amid the Lib Dems’ and the Tories’ oh-so-worthy pleas for Chilcot to get a move on. In an election year, they would probably have liked Newish Labour to be forced to confront the sins of its fathers; to be forced, once more, to talk in agonising detail about one time leader and full-time bad guy Tony Blair, dodgy dossiers and those darned WMDs. But there’s more to the yearning for Chilcot’s arrival than political point-scoring. After all, it’s not just Tories and Cleggers clamouring for Chilcot to turn up — it’s the left-leaning, too, from Labourites to liberal interventionists. ‘Do we not deserve the truth?’, asks the Labour-supporting Mirror. The Independent’s Andreas Whittam Smith opted for the unctuous: ‘Healing cannot begin until Sir John reports. That is the urgency.’

But what can the Chilcot report really do? What can it tell us that we don’t already know? Yes, perhaps we don’t know exactly what then US President George W Bush said to ‘Yo’ Blair in one of their 150-or-so private messages. Perhaps we don’t know exactly how the case for the Iraq War was developed in the myriad meetings between key actors. But what does that really matter? We surely know enough. There have been countless books with titles like Lies, Damned Lies and Iraq. There have been several prior inquiries and reports: Lord Hutton’s into the circumstances surrounding the death of David Kelly, a British weapons inspector; Lord Butler’s into pre-war ‘intelligence failures’; and the US Senate intelligence committee’s phase II report, which featured the damning quote: ‘The [Bush] administration made significant claims that were not supported by the intelligence.’ And, most striking of all, there is the mess of Iraq itself, torn asunder by invasion, and now torn apart by Islamist insurgency. There can be no sentient being outside the Euston Manifesto Group who still thinks the Iraq War was a good idea.

Yet not only do we surely know enough now about the Iraq War to condemn it, to criticise the vainglory of its undertaking, and the barbarism of its consequences; as spiked’s opposition to the invasion showed, we knew enough then to condemn it, to criticise the vainglory of its undertaking, and the barbarism of its consequences. We knew enough then to say that intervention, as an idea, was wrong because it would trample on the potential of the Iraqi people to determine their own future. We knew enough then to say that you can’t shock and awe a country to democracy. The question of WMDs was tangential, UN legitimacy irrelevant. What ought to have mattered then, as it ought to matter now, was that, politically and morally, it was possible to know that the Iraq War was wrong. You didn’t need a State Department report on intelligence failures, or a judge-led inquiry into ‘what happened’ to tell you this; you just needed moral and political backbone.

And that is what those British politicians and commentators now craving Chilcot’s elixir of truth singularly lacked. Some sought refuge in legalism, demanding that UN Security Council Resolution 687 be satisfied (that is, prove Saddam had WMDs) before invasion commenced; some went with the government line that Saddam was just really good at hiding his armoury; and some just thought that getting rid of a tyrant was the Right Thing To Do. Little wonder, given the nature of the debate at the time, that in March 2003, 412 MPs voted to invade Iraq, while only 149 said no.

This is why the Chilcot report has taken on this hazy redemptive quality: it promises to make a simple sense of what happened, to exonerate those who argued so ineffectively against the war, those whose moral and political conviction was found wanting. And it promises to salve their conscience. ‘I am guilty along with 416 MPs in 2003 who voted to topple Saddam’, wrote then Labour MP Dennis McShane this week. ‘I believed… that Saddam had played fast and loose with UN inspections and therefore probably did have WMDs.’ For the likes of McShane, Chilcot promises absolution. He is the priest come to assuage the guilt of the congregation of Westminster.

And how might a mere report achieve this? By revealing that Blair and Bush, and no doubt an assortment of shadowy neocons, cooked the whole thing up among themselves. That is the promised land of the Chilcot report, the longed-for redemptive moment — because that is the point when all the blame can be heaped on to Blair and Bush. And when that point comes, those who approved of intervention can say they were tricked, that the Iraq War was a product of the no-doubt oil-grabbing deceptions of Bush and Blair.

That point won’t ever come, of course. The search for the smoking gun, the hunt for the message that reveals Blair’s subterfuge, is as futile as UN weapons inspector Hans Blix’s search for Saddam’s WMDs. Blair’s problem was never mendacity; it was self-righteous, God-consulting sincerity. Not that that matters for those determined to believe that it was Blair’s fault. If Chilcot can’t deliver ‘the truth’, then someone else will have to come along. In this infernal attempt to pass the buck for the Iraq War, the definitive report — the ‘truth’ — never arrives.

There is a blood-soaked irony to this obsession with the Chilcot report. It promises to provide ‘lessons from the Iraq War’. But, as shown by the ruinous interference in Libya, and the bungled showboating over Syria, the principal lesson of the Iraq War is one Britain’s ruling elites steadfastly refuse to learn: that do-gooding, feelgood Western interventions always make things worse.

Tim Black is deputy editor of spiked.

Picture by: PA images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.