Torture report: war is no place for the law

No one benefits from the invasion of lawyers into the sphere of war.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Early nineteenth-century military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously described war as ‘the continuation of politics by other means’ (my emphasis). It’s an aphorism that aptly summarises the essence of war as being a conflict that is waged for political ends, but which uses non-political means. Indeed, wars use barbaric means that would be outlawed and criminalised if it were not for these political ends. This doesn’t imply that the ends always justify the means, but it does imply that the means may be justified in the name of a greater political goal, such as a defence of territory, sovereignty or self-determination. Ultimately, Clausewitz recognised that wars need to be justified, or criticised, on a political basis.

Today’s military discourse rewrites Clausewitz’s aphorism: ‘War is the continuation of politics by legal means.’ It’s an aphorism that aptly summarises the essence of modern-day Western warfare, which is governed not by politics but by legalism, complete with a multitude of lawyers keeping a constant watch on the means deployed. According to this approach, the ends of war are irrelevant. Certain means will be outlawed and criminalised regardless of political goals. Ultimately, this new military discourse does not justify wars on a political basis; its yardstick is legality.

By replacing the word ‘other’ with the word ‘legal’ in Clausewitz’s aphorism, the West’s new military discourse is not only seriously undermining its ability to mount a political justification for war; it also means its opponents are losing the ability to criticise wars on anything other than a legal basis.

The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were waged by Western leaders who lacked a popular political basis for intervention. US president George W Bush and UK prime minister Tony Blair sought to compensate for this lack of popular support by claiming a legal right to invasion. With Afghanistan, the West relied on a United Nations resolution passed three days after 9/11 that called on ‘all states to work together urgently to bring to justice the perpetrators, organisers and sponsors of these terrorist attacks’. With Iraq, the West relied on a UN resolution of November 2002, which offered Saddam Hussein’s Iraq ‘a final opportunity to comply with [the UN’s] disarmament obligations’. But by basing their arguments for intervention on legal interpretations of UN resolutions, Western powers on both sides of the Atlantic simultaneously laid the ground for a succession of campaigners to oppose these wars with legal arguments.

Politicians of an earlier era sought to justify wars by claiming a political need to defend the realm or some other political principle. Indeed, the very notion of an unlawful war is a recent invention (and fiction) in the absence of: any laws passed from which illegality can be judged; any court that can determine an illegality; and any organisation that can enforce legality. These absences remain and explain the interminable arguments conducted by lawyers (invariably expressing a subliminal political perspective) on whether a particular intervention was legal.

The Bush and Blair approach to war in the early part of the twenty-first century ushered in the discourse that war is the continuation of politics by legal means. And with the invaders having set out their legal case, it was perhaps inevitable that the opponents of war would respond with countervailing legal arguments. Hence, since 2001, the rights and wrongs of wars have come to be decided, not by politicians, but by lawyers ignoring political principles in favour of the UN Charter, UN resolutions, legal precedents and countless articles written by learned law professors.

This is problematic for three reasons. First, and most importantly, legal frameworks are shaped by legal principles and legal precedents that constrain judges to decide cases in particular ways. Legal principles and precedents are suitable for deciding politically neutral issues, such as whether a contract has been breached, but they are unlikely to be suitable for deciding politically charged issues such as whether a state has a right to wage war.

Secondly, when law meets war, there can be only one outcome: the state’s ability to wage war, and hence to defend an important political principle, will atrophy. Lawyers will scrutinise the case for war and find it wanting. They will suggest alternatives which are more proportionate and less warlike. When war commences, they will find breaches of umpteen charters and will find victims of human-rights abuses with a legal right to the truth and to compensation. And, just for good measure, the lawyers’ learned considerations and judgements will cost a fortune and will take an age to be delivered.

Thirdly, the legal consideration of any issue is the preserve of lawyers. The legality or illegality of an issue is a technical one that engages laws, their legal interpretation and their application. This legal framework is determined in a court of law by a judge who lays down the law after hearing legal submissions from lawyers. The court of public opinion is a mere bystander to this process. Turning political issues into legal ones is a sure way of disenfranchising and disengaging the public. A state that turns an issue as important as warfare into a legal one would be better described as a juristocracy than a democracy.

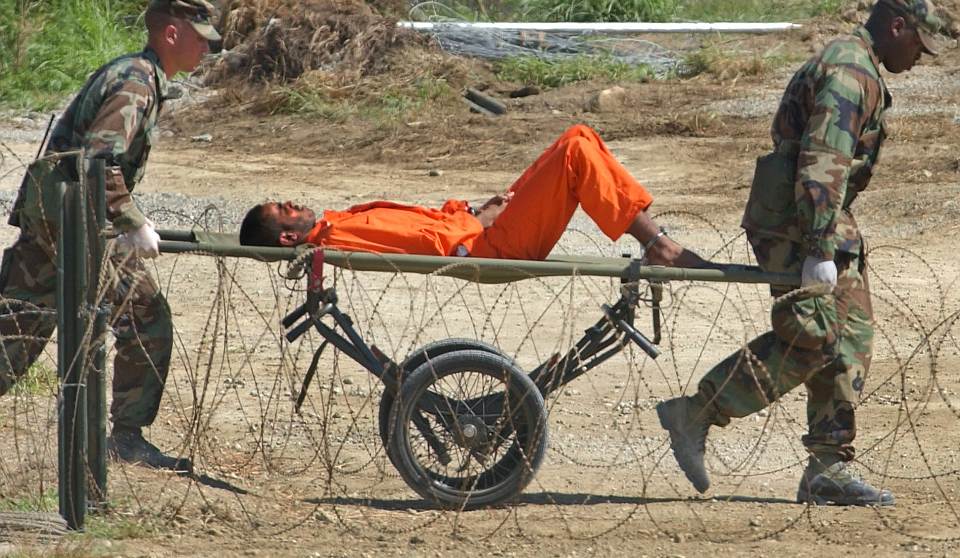

That America and Britain are on the road to juristocracy has been highlighted by two reports released on both sides of the Atlantic this month. In America, the US Senate released a 500-page report on the use of torture by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the years after 9/11 as part of America’s ‘war on terror’.

Torture is illegal. But only recently has it become a way of defining and evaluating a nation’s wars. In an earlier era, warring states practised torture yet were able to prevent these illegal activities from undermining their war efforts. The UK, for example, used the now infamous five techniques of interrogation (prolonged wall-standing, hooding, subjection to noise, deprivation of sleep, and deprivation of food and drink) at an early stage of its war with Irish nationalists in the early 1970s. When it became public knowledge, prime minister Edward Heath stated that the practice was illegal and would not be used again. The issue did not undermine the government’s stance, and legal issues surrounding torture never became a central part of any campaign for or against British involvement in Northern Ireland. (Although, as befits the central role that law now plays in war, it is interesting that the Irish government is now taking the infamous ‘torture’ case back to the European Court of Human Rights in an attempt to persuade it to revise its 1978 judgement that Irish prisoners had been subjected to ill-treatment but not torture.)

The Senate’s report on the CIA’s use of torture after 9/11 seems likely to define the character of Bush’s ‘war on terror’. Opponents of this war, and many of its proponents, are putting the illegality of torture centre stage. Ben Emmerson, the British barrister and UN rapporteur for human rights, captured the legal critique of the ‘war on terror’ when responding to the report: ‘The individuals responsible for the criminal conspiracy must be brought to justice, and must face criminal penalties commensurate with the gravity of their crimes.’ And with a nod to capturing high-level politicians in a legal net, he noted ‘the fact that the policies revealed in this report were prioritised at a high level within the US government provides no excuse whatsoever. Indeed, it reinforces the need for criminal accountability.’ Political arguments either for or against the ‘war on terror’ have been all but silenced.

No sooner had the report been published than the hunt started in Britain to determine what the Guardian described as ‘the key question’; namely ‘whether Britain was complicit in any operations that involved torture and, if so, in what exact ways?’. The Guardian claimed that ‘British democracy still urgently needs to get to the truth’, and to do so, if necessary, by pursuing cases ‘in the courts’.

‘Criminal accountability’, to use Emmerson’s phrase, rather than any form of political accountability, is what opponents of Bush’s ‘war on terror’ seek. This problem is just as prevalent in the UK as it is in the US. The Blair government’s involvement in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq was constantly dogged by questions about its legality. Opponents of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq brought so many legal challenges that there have been no less than four inquiries into the alleged abuse of foreign nationals: Baha Moussa, reported in 2011; Al-Sweady, reported last week; an ongoing investigation by the Iraq Historic Allegations Team into over 1,000 allegations of unlawful killing and mistreatment; and the Gibson Inquiry into mistreatment of detainees, wound up in 2013. Furthermore, there have been more than 200 judicial-review applications, and more than 300 personal-injury claims from Iraqi and Afghan nationals. The UK defence secretary Michael Fallon recently said that legal claims from the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have been lodged against Britain on a ‘virtually industrial scale’.

The fact that the Al-Sweady inquiry, the second striking report published this month, found all the serious Iraqi complaints against British servicemen to be baseless has prompted many commentators to question the wisdom of this legal approach to war. Writing in the Daily Mail, Richard Littlejohn posed this scenario from April 1945: ‘Allied forces crossed the Rhine and are advancing towards Berlin, closely followed by a team of lawyers hoping to drum up allegations of war crimes against British soldiers. Solicitors from Birmingham-based Shyster & Shyster Ltd scour the battlefield, encouraging the Germans to sue the army for human-rights abuses. You could be entitled to compensation, they tell their potential “clients”.’

It’s a scenario intended to draw a parallel with the numerous legal claims made by a British lawyer, Phil Shiner, on behalf of Iraqis who are seeking compensation for ill-treatment during Britain’s involvement in the Iraq War. So, after noting that Field Marshall Montgomery in 1945 would ‘have rounded up these spivs and put them in front of a firing squad for treason’, Littlejohn asks this interesting question: ‘Can anybody please explain the difference between that scenario and the odious Phil Shiner pursuing an opportunist, politically motivated vendetta against our troops in Iraq?’

Littlejohn can’t see a difference between the two scenarios, so he concludes by noting how ‘those soldiers falsely accused by Shiner’s clients would be happy to form a firing squad’.

Littlejohn’s outrage is misplaced insofar as he’s seeking to put a single person in the crosshairs: Shiner. But Shiner is bringing legal claims, many of which are successful, because the British establishment now seeks to clothe its wars in the respectability of law. It was the UK government, not Shiner, that set up the four inquiries into alleged abuses of detainees, and it is the UK Supreme Court that recently sanctioned the bringing of human-rights claims in respect of injuries suffered on the battlefield.

But war is the continuation of politics by other means. In treating war as the continuation of politics by legal means, the British establishment has far more in common with its critics than either side would care to admit. Legalism dominates mainstream political opinion in the Western world today. It is legalism as a political concept, and particularly its application to war, that needs to be put in the crosshairs. And it’s time to form a firing squad to purge this concept from the battlefield.

Jon Holbrook is a barrister based in London. He was shortlisted for the Legal Journalism prize at the Halsbury Legal Awards 2014. Follow him on Twitter: @JonHolb.

Picture by: PA images.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.