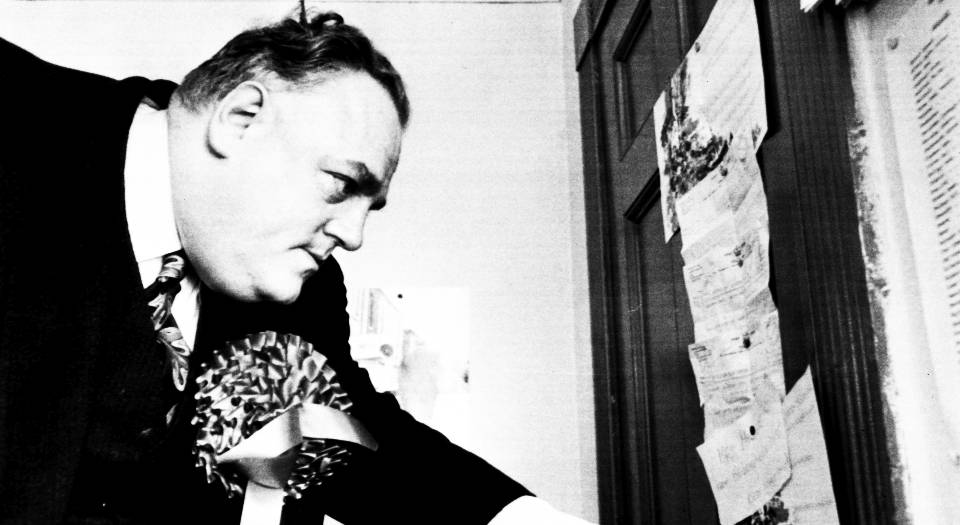

Cyril Smith: no justice for dead men

The moral crusade against child abuse invents its own truth.

It may not be possible to libel the dead, but, as the Labour MP Simon Danczuk has been busily demonstrating, you can find them guilty of child abuse.

Up until now, Danczuk, the MP for Rochdale, was most famous for complaining to the police about the justice-perverting actions of Chris Huhne, the former Lib Dem energy minister. But since the autumn of 2012, when the Jimmy Savile scandal broke across British society like a wave of excrement, Danczuk has been pursuing an even bigger Lib Dem beast, namely Cyril Smith, the one-time Lib Dem MP for Danczuk’s constituency, who died in 2010 aged 82.

‘Young boys were humiliated, terrified and reduced to quivering wrecks by a 29-stone bully imposing himself on them’, Danczuk said of Smith to a hushed House of Commons in November 2012. Danczuk’s allegations, based on the statements of some of Smith’s putative victims, quickly became treated as fact. First, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) said that had the allegations been made today, Smith would have stood trial. Then Greater Manchester Police trumped the CPS by releasing a statement to ‘publicly acknowledge that young boys were victims of physical and sexual abuse committed by Smith’.

So that was that. Just two years after his death, but many years after the allegations were first made, Smith was effectively found guilty of child abuse. Any notions of justice, of due process, were seemingly of no import. After all, Smith was dead. That this ought to have made the authorities, and the press who reported the Smith allegations as matters of fact, a little reticent didn’t seem to occur to anyone. Instead, Smith’s absence, and the impossibility of scrutinising the claims, of interrogating the evidence, was seen as an opportunity, not an impediment – an opportunity to expedite a guilty verdict.

And now Danczuk has followed up the original allegations with a book detailing Smith’s alleged crimes, Smile for the Camera: The Double Life of Cyril Smith, which, for fans of the sordid and tawdry, was serialised in the Daily Mail last week. There was no question of doubt, reasonable or not. And the protestations of Smith’s family, who pointed out that the police had dropped the case back in the 1970s because of a lack of evidence, have been dismissed. As the Telegraph was content to describe it: ‘Danczuk was confronted with irrefutable evidence that Smith was a predatory paedophile who had used his power and influence to prey on hundreds of boys, some as young as eight, for over four decades.’ There you have it: ‘irrefutable evidence’. Case closed.

Except it’s not really. There’s been no scrutiny of the allegations, and not even a sceptical glance cast Danczuk’s way. Instead, there has just been amassed credulity from pundits and politicians, including from the Lib Dems themselves, with their leader Nick Clegg falling over backwards last week to express his disgust towards someone he had eulogised as ‘one of the great MPs of his day’ in 2010. Why has there been so little questioning? Why have allegations simply been taken as fact? Why have so many not just gone along with the claims against Smith, but eagerly imagined that there are deeper and darker secrets still to emerge?

These questions ought not to suggest that Smith was sin-free, just that there has been nothing proved. But then this focus on Smith, this demonisation of a figure who, like Jimmy Savile, was already conveniently out-of-time by the time of his death, and deemed something of a weird grotesque, has very little to do with justice. Rather, what’s driving the current excavation of the past of distinctly unfashionable figures such as Smith is a moral crusade, in which combating child abuse has become the one unquestionable moral cause of our time.

As Frank Furedi has explained elsewhere, a moral panic is circumscribed in space and time, and is motivated by the need to affirm an existing moral consensus. But a moral crusade is different. Far from being circumscribed, it is infinitely extendable and seemingly interminable, always sighting and fighting an evil in our midst. And, unlike a moral panic, it exists in the absence of a moral consensus. Indeed, the object of a moral crusade is to create a notion of the good in the process of hunting down an evil. Indeed, for the crusaders, be they campaign groups, politicians or commentators, they are engaged in a moral project, a project of moral construction, alerting the rest of society to the bad things which – out-of-sight, hidden and behind closed doors – are being carried out by bad men.

Here’s Danczuk on Smith: ‘He was on every chat-show host’s sofa, frequently on television and even appeared on Top of the Pops dancing with the biggest girl band in the world at the time, Bananarama. But his celebrity status allowed him to keep a very dark secret well hidden. Cyril Smith was a predatory paedophile… Pillars of the establishment certainly need shaking. And big questions remain. Why was a paedophile politician investigated by police for the best part of 40 years never prosecuted? I’ve seen the horrific consequences of child abuse and how it ruins lives. And that’s why I’m taking a strong stand. There’s no place for paedophiles in public life – and they cannot and should not be protected by the establishment.’

The signs of the crusade are all there: Danczuk’s possession of the knowledge of the ‘very dark secret’; the willingness to ‘shake the pillars of the establishment’ in the pursuit of this truth; the moral self-aggrandisement of ‘taking a strong stand’; and the suggestion that even if Smith’s gone, the crusade must continue – ‘There’s no place for paedophiles in public life’. Little wonder the usual processes of criminal justice seem to be of no concern to Danczuk. He already assumes what he needs to prove – the existence of paedophiles in public life. The important thing now, in Danczuk’s mind, is the process of crusading, the process of raising awareness of the problem in our midst.

Given the crusaders’ unshakeable conviction that child abuse is lurking behind every closed door, from Westminster to the BBC, it is not a surprise that their hunt frequently sounds like unabashed conspiracy theory. Smith or Savile are not isolated exceptions; no, according to crusading cliché, they’re tips of a submerged iceberg of abuse, indicators of a far greater evil at work. As one commentator in the Guardian admits: ‘Political friends of mine, more savvy than me but no more inclined to conspiracy theory, say they suspect that even the intelligence services contained powerful figures protecting fellow paedophiles in those days. There is more to tumble from the closet.’ Danczuk, like his fellow Labour MP Tom Watson, is likewise convinced that there is/was a paedophile ring operating among Britain’s political elite. ‘I’m certain there were other politicians involved as well as Cyril as part of a paedophile network. Whether the full truth of this eventually emerges will ultimately depend on the courage of the political classes and the authorities. Let’s hope some good men and women are prepared to do something about it.’ ‘Truth’ here is something that is simultaneously known to the likes of Danczuk – there is a political paedophile network – while also to be discovered, providing men and women are moral enough, ‘good’ enough, ‘to do something’.

To cast doubt, to raise questions of the crusade, is to mark yourself out as someone who is not ‘good’, who is not ‘prepared to do something’. Which is one of the reasons why there are so few willing to resist the crusading logic. Clegg, by refusing to launch an investigation into how Smith ‘got away with it’ without anyone in the Lib Dems doing something about it, is finding this out to his cost. Anyone unwilling to find and then parade a skeleton from their closet is deemed suspect.

One thing’s for sure: the Cyril Smith child-abuse scandal will not be the last to ‘shake the pillars of the establishment’. This is not because there really was, or is, a paedophile network operating within Britain’s corridors of power waiting to be unearthed. Rather, it’s because, by its very nature, the crusade needs to assume the continued existence of an evil to be righted, and it will continue to do that by pointing towards that which is hidden. While such a crusade might make its advocates feel tremendously righteous, the damage it will do to public life, casting all institutions and individuals in a suspect light, will be profound.

Tim Black is deputy editor of spiked.

Picture: PA/PA Archive/Press Association Images

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.