We are all Ayatollahs now

25 years on from that fatwa, everyone now demands the destruction of things that offend them.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

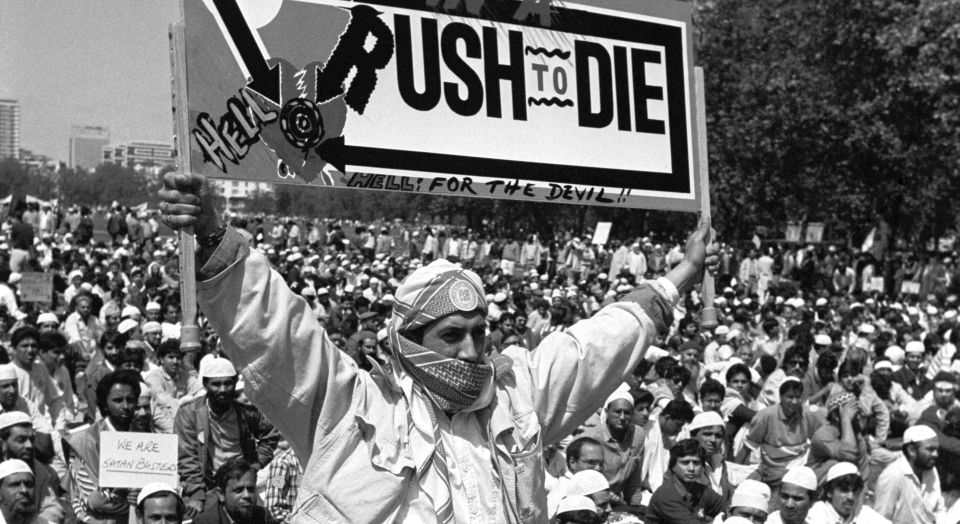

Today is the twenty-fifth anniversary of Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa against Salman Rushdie for writing The Satanic Verses. ‘I am informing all brave Muslims of the world that the author of The Satanic Verses… along with all the editors and publishers aware of its content are condemned to death’, said Khomeini on 14 February 1989. The fatwa had many tragic consequences, the most dire being the murder in 1991 of the Japanese translator of the novel and the violent attacks on others involved in publishing it. But perhaps its most insidious impact has been its contribution to the idea that censorship is a foreign thing, that extreme sensitivity to slight and arrogant demands for the squishing of ‘offensive’ material are alien emotions, imposed on or imported to our otherwise tolerant society by faraway men in beards and cloaks. This narrative misunderstands both the origins of the fatwa itself and the nature of today’s highly censorious cult of offence-taking.

Ever since Khomeini said in a radio broadcast that Rushdie should be put to death for writing a novel that was ‘against Islam, the Prophet of Islam and the Koran’, many Western thinkers and observers have been promoting the idea that our longstanding culture of tolerance, including of offensive material, is being threatened by foreign groups or peoples who are fundamentally intolerant. The fatwa is seen as opening up a gaping faultline between the core Western belief that no one ‘should be killed, or face a serious threat of being killed, for what they say or write’ and Muslims’ conviction that no one should be free to ‘insult or malign Muslims [by disparaging] the honour of the Prophet’. This idea that the fatwa pointed to a new global divide between those who feel a strong attachment to freedom of speech and those who harbour a religious-inspired hostility towards it was summed up in a piece by Peregrine Worsthorne in the Sunday Telegraph five days after Khomeini issued his fatwa. ‘Islamic fundamentalism is rapidly growing into a [great] threat of violence and intolerance’, he said. In the years since 1989, the book-burning Muslim, the bearded yeller for the beheading of those who insult Islam, has been many Westerners’ go-to image of intolerance.

The notion that today’s ostentatious offence-taking and growing intolerance of blasphemous, scurrilous or ‘hurtful’ content is an alien phenomenon is wrong in two important ways. Firstly it is wrong because it skews the timeline of the fatwa. In many people’s minds, it was the fatwa, issued from that hotbed of Islamist thinking, Iran, which unleashed the fury against The Satanic Verses. In fact, the fatwa came six months after the publication of the novel, and in those six months there was wild, furious protesting against the novel – a great deal of it in the West.

The novel was published in September 1988. The first call for it to be banned came from Khushwant Singh, a King’s College-educated secularist Indian writing in the respectable news journal, Illustrated Weekly. Singh was concerned about the reaction the novel would provoke among Muslims. There followed an intense letter-writing campaign in the US, with both Muslim groups and their supporters bombarding Viking Press with angry condemnations for publishing Rushdie’s novel, and occasionally with death threats. Twice in December 1988, two months before Khomeini issued his fatwa, Viking staff had to evacuate their offices after receiving bomb threats. Some Viking executives took to wearing bulletproof vests. In Britain, there were book-burnings of The Satanic Verses in Bolton in December 1988 and in Bradford in January 1989. The latter was attended not only by angry Muslims but also by local politicians and the Bishop of Bradford. That is, a British man of the cloth stood by as The Satanic Verses was stuck on the end of a stick and held above a fire a full month before an Iranian man of the cloth issued his death sentence against Rushdie.

The extreme sensitivity to The Satanic Verses was expressed in Western communities months before Khomeini broadcast his fatwa in a pretty transparent attempt to milk the already existing international controversy for his own political benefit. The angst over Rushdie’s novel was as much a product of the very Western ideology of multiculturalism as it was of an Iranian mullah’s authoritarian urge to protect his faith from any slight. The pre-fatwa letter-writing campaigns, bomb threats and book-burnings in the West did not speak to an invasion of intolerant Muslims into our societies; after all, Muslims had been moving to and living in Western countries for many decades prior to 1988/89. No, it spoke to the growing influence of the multicultural idea that every religious community and identity group should be accorded respect, none should be viewed as better than any other, and all should be protected from the gruff language and ridicule of observers or outsiders. It was those new and divisive ideas, the jettisoning of the old universal values of tolerance and citizenship in favour of cultivating communal identities and obedient respect for all cultures, which were fundamentally the spark for the widespread pre-fatwa anger about The Satanic Verses in the US and the UK.

The Western nature of much of the upset over Rushdie’s novel was further captured in the equivocation and even outright cowardice of many leading Western politicians and thinkers in response to calls for the novel to be banned. So no less a figure than a former president of the United States – Jimmy Carter – condemned Rushdie for failing to be ‘sensitive to the concern and anger’ of Muslims, and for making ‘a direct insult to those millions of Muslims whose sacred beliefs have been violated’. One of the West’s most instantly recognisable literary names, John le Carre, said writers should not be free to be ‘impertinent to great religions with impunity’. Some Western bookstores refused to stock Rushdie’s novel or cancelled launch events for it. The protesting of Western citizens and politicians over Rushdie’s failure to be sensitive, much of which occurred pre-fatwa, should shoot down the myth that it was Islamic fundamentalism that corrupted our traditions of tolerance and freedom of speech.

The second thing today’s fatwa narrative gets wrong is that it has a tendency to depict Muslim groups, or sometimes religious groups more broadly, as the sole or at least key source of censorship today. The only time modern-day defenders of freedom of speech seem to get really excited is when a mob of angry Muslims demands the banning of a play or the pulping of a book, because taking a stand against such demands allows them to dramatise and even internationalise their war in defence of freedom. It allows them to depict the threat to freedom of speech as a clash-of-cultures problem, pitting respectable Western authors and artists against intolerant Bible-bashers or Koran-carriers. This overlooks the true motor of the culture of offence-taking and censorship today, which is moral cowardice among the cultural elites of the West, not moral fury on the part of Muslim groups.

When Western publishing houses and theatres do hold back from publishing or displaying material critical of Muslims, often it isn’t because massive mobs have been hammering on their doors but rather because they themselves feel uncomfortable with expressing strong, possibly offensive opinions. So in 2008, Random House decided not to publish Sherry Jones’ novel The Jewel of Medina, which tells the story of the Prophet Muhammad’s relationship with his 14-year-old wife Aisha, after one academic reader said it ‘might be offensive to some in the Muslim community’. Both the London Barbican and Royal Court Theatre have in recent years cut or cancelled plays critical of Islam on the entirely pre-emptive basis that they might stir up Muslim anger. In each case, it wasn’t threats from agitated Muslims that caused the censorship – rather, elite fear of the spectre of agitated Muslims generated self-censorship. Today’s concern about what ‘might be offensive’ to Muslims is best understood as an externalisation of the cultural elite’s own internal doubts about art, politics and debate, a projection of their own uncertainty about what is sayable and unsayable on to an imagined mass of seething Muslims.

In essence, what the fatwa has provided over the past 25 years is a justification for the cowardice of the West’s own gatekeepers of knowledge and publishers of literature, who, feeling increasingly unsure about what can be said and depicted in this era of multiculturalism, cultural sensitivity and professional offence-taking, often display an instinctive urge to hold back, to pulp, to unpublish. Unwilling, understandably, to say, ‘We’re just not confident that we have the right or the authority to publish this controversial content’, they instead say, ‘Muslims might be offended… and remember that fatwa?’. The fatwa has become an all-purpose foreign spectre hidden behind by many within Western elites who simply lack the cojones to publish and be damned or to uphold the right to be offensive and to express oneself freely, openly and, yes, provocatively.

And of course, this in turn inflames some Muslim groups’ belief that they have the right to surround themselves with a forcefield against offence. When Muslims, usually in small numbers, do gather in a British or American city to demand the squishing of a book or cartoon, we can’t really be surprised. Our uber-sensitive society, our top-down culture of respect for identity and institutionalised inoffensiveness, has given them a licence to take offence. Our moral cowardice inflames their narcissistic demands for censure. It’s a vicious circle.

Finally, let us not forget that it isn’t only Muslims who call for the obliteration of offensive material in the twenty-first century. In Britain over the past couple of years, mobs of transsexuals have successfully had a newspaper article banned, gay-rights activists got an advert removed from the side of a bus, online ‘trolls’ have been chased by Twittermobs, arrested by the police and imprisoned for being ‘grossly offensive’ to women and minorities. The methods are different to those used by Khomeini, but the instinct is precisely the same – to punish those who dare to mock or offend us. We are all Ayatollahs now.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

Picture: PA/PA Archive/Press Association Images

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.