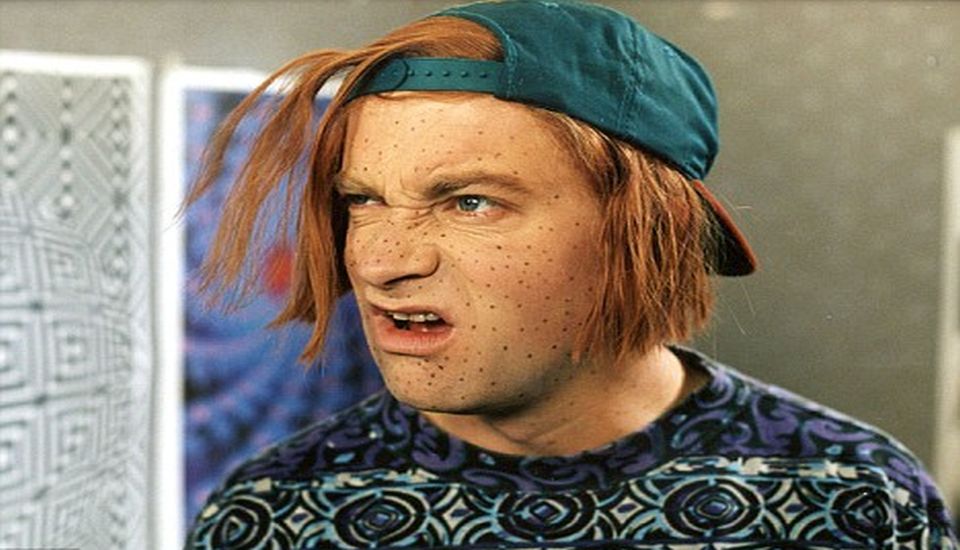

Who are you calling an adolescent?

Tom Slater, 22, slams the extension of adolescence to 25.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

When you’re a kid, adulthood is something not only aspirational but intoxicating. Every year that you edge closer towards 18 brings with it new freedoms and experiences. At first, it’s the chance to stay out later, drink, cavort and have sex that is perhaps the biggest attraction. But as you grow older and wrest yourself completely free of the parental yoke, the feeling of being 100 per cent responsible for your own money and your own choices, and, not to get too grandiose about it, a master of your own destiny, is a powerful one.

Now that I’m 22, a graduate, working full-time and moved out of my leafy suburban hometown, leaving my Pokémon cards and my childhood behind, I genuinely feel that I’ve ‘arrived’. But this week, the medical profession gave me and my fellow Generation Y-ers a collective pat on the head when new psychological guidelines were published extending the endpoint of adolescence from 18 to 25. Now, even patients over the age of 18 will be treated as being in ‘late adolescence’.

It was justified as a purely clinical step, reflecting new discoveries in the field of neuroscience that show our brains continue to develop into our early thirties. ‘This is particularly important in terms of social reasoning, planning, problem-solving and understanding’, said clinical psychologist Sarah Helps on the BBC News website. ‘The brain is reorganising itself, which then means that different thinking strategies are used as your brain becomes more like an adult brain.’ So apparently even men and women in their 20s are still ‘developing’.

If I may for a moment express myself in a way befitting my recently restored immaturity, this is a load of bollocks. Aside from the obvious physical aspects of coming into bloom (development of new hair, odour, fluids, etc), the boundary between childhood and adulthood has always been socially defined. Indeed, in generations past, when people were ushered into the workplace and the marital bed before many kids nowadays are even out of school, the concept of adolescence, as a kind of grace period between the one stage and the next, didn’t even exist.

As has often been the case throughout its history, psychology tends to consolidate and reaffirm cultural values. The recent extension of adolescence is no different. We live in a time when being a grown-up has become something fraught and problematic, a world of professional drudgery, traumatic relationships and burdensome responsibility. Adult life isn’t something to be lived, apparently, but to be helped through by all manner of therapeutic ‘support’. The alleged ‘stress epidemic’ of the past decade, was a prime example of this – a completely invented problem that effectively painted the inevitable strains of adulthood as a veritable health crisis.

During the New Labour years, state hectoring about health, as well as increasing intervention into personal and family life, served to undermine people’s autonomy and self-sufficiency. The new psychological guidelines on adolescence are merely a clinical expression of this infantilising cultural shift.

For those who grew up in this tentacled state-led embrace, the effect on independence has been particularly devastating. Today, the school system micromanages every playground spat, while even at university student unions hamper young people with touchy-feeling concerns about ‘wellbeing’, and an increasingly perverse obsession with their sexual etiquette. Brought up in an atmosphere where you’re increasingly encouraged to abdicate responsibility for your affairs, it’s little wonder that, as some studies suggest, as much as 32 per cent of 25- to 39-year-olds choose to live at home with their parents and be done with the trials of independence altogether.

Yet while the roots of this so-called ‘Peter Pan generation’ are pretty clear, there really is no excuse to have your mum wash your socks into her dotage. Reacting to the new guidelines, one Guardian writer insisted that, with rent prices skyrocketing, the job market in the toilet and the economic situation looking bleak, leaving home is simply not an option for most young adults. Nevertheless, she suggested we should still respect them as autonomous adults, even if they’re not yet paying their way: ‘Even if they’re still living in the family home, they will have experienced independence in other places, whether that’s at school, university or among colleagues.’ While it may be true that some of today’s young won’t enjoy the same prosperity as their parents, it’s deeply patronising to suggest that even the ‘experienced’ and clearly employed young professional described by this Guardian writer wouldn’t have the nous and the determination to move out, whatever it takes.

So, to my ‘late adolescent’ brethren I say: ignore the patronising quacks and the cloying stay-at-home apologists. Strike out on your own and display the independence, the gumption and the determination that are the definition of adulthood.

Tom Slater is assistant editor at spiked.

Picture: PA Images

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.