Democracy: in defence of the herd

The masses, even the unintelligent ones, are perfectly capable of doing democracy.

When New York Times columnist David Brooks recently wondered if Islamist-leaning Egyptians have the necessary ‘mental equipment’ to do democracy properly, there was a chorus of teeth-gnashing in the progressive media and the Twittersphere. Brooks was branded a bigot and ‘giant dick’ for saying the Egyptian masses ‘lack the basic mental ingredients’ for democracy.

Yet just a few days later, British liberals, the same folk who gave Brooks a Twitter roasting, were wondering if the British masses possibly lack the basic mental ingredients to do democracy. Of course, these non-American observers are way too savvy to use Brooks-like words such as ‘mental’ and ‘equipment’ to express their concern about the little people’s knowledge deficit. Instead, they fretted over Brits’ ‘skewiff’ understanding of basic social facts. Yet the content of their argument was the same as Brooks’s: namely that some people, Them, are not capable of serious democratic engagement.

The trigger for this outpouring of elitist angst about the British mob’s ill-preparedness for democracy was an Ipsos Mori poll which found, according to a headline in the Independent, that ‘the British public [is] wrong about nearly everything’. Having carried out a phone survey of 1,015 people aged between 16 and 75, Ipsos Mori found that public opinion is ‘repeatedly off the mark’ on numerous social issues.

For example, on average those polled thought £24 of every £100 of welfare benefits is fraudulently claimed, when actually it’s only around 70 pence of every £100. Respondents thought that about 31 per cent of the British population is made up of recent immigrants, when in fact it’s 13 per cent. They overestimated the number of under-16s who get pregnant each year by 25 times, thinking 15 per cent of girls get knocked up, when it’s closer to 0.6 per cent. And so on. As the undertone of all the rather gleeful media coverage of the poll would put it, if it had the nerve to state itself nakedly, ‘British people are really fucking stupid’.

The poll generated much head-shaking among clever people. The executive director of the Royal Statistical Society wondered how democracy can function when the demos is so dim-witted: ‘How can you develop good policy when public perceptions can be so out of kilter with the evidence?’ Commentators said the poll is proof that ‘the gulf between perceptions and reality is quite staggeringly wide’. Under the heading ‘The problem with democracy’, one observer declared: ‘The public is ignorant about politics and lacks even the basic facts that it would need to make sound judgements about political issues.’

The message of the poll, and of the media’s told-you-so whooping cleverly disguised as social concern, is that where we are capable of partaking fully in democratic governance, they – the tabloid-addled oiks who falsely believe every teen is pregnant and every benefits claimant is on the make – are not. Commentators implicitly made a distinction between a caste of experts well prepped for policymaking and a horde of ignoramuses whose daftness on basic social matters makes their input to policymaking a potentially dangerous thing. As some observers said, it’s possible politicians will play to the ignorance of the public gallery on issues like benefits and crime, thereby further denigrating democracy. Wouldn’t democracy be a far better thing without the grubby demos?

There are two things to say about the increasingly popular idea that ill-informed everyday people are not the ideal folk to have deciding who rules and what these rulers should do. The first is that ‘ordinary people’, as the media calls them, don’t have a monopoly on prejudice. Yes, it’s true, there are people out there who are wrong about the welfare system or about immigration. I often bump into them. I argue with them. But fact-lite prejudicial thinking is just as rife, if not more so, among the cultural elites.

What is striking about the Ipsos Mori poll is the issues it focused on: immigration, teen pregnancy, benefits cheats. These are quite obviously tabloid flashpoint issues, on which it is known that people of a working-class persuasion in particular have strong, often OTT views. But imagine if you polled members of the cultural and political elites about the true statistical nature of, say, obesity, or the impact of junk food, or the dangers of second-hand smoke, or something else that taps into their prejudices concerning the slovenly, destructive behaviour of the mob. How wrong would they be about those issues? Massively, I’d say.

In fact, if there is a difference between so-called expert cliques and the man in the street, it’s that the former have become dab hands at disguising their prejudices as research-based viewpoints. So on an issue like obesity, they move the goalposts, redefine what obesity means, in order to make their prejudice about ordinary Brits being corpulent and lazy into a ‘true fact’. On something like second-hand smoke, they’ll elevate research which claims it is dangerous, and downplay research which says it isn’t, in order to make their moralistic disdain for smokers and their authoritarian ban on public smoking seem like the actions of research-respecting minds, rather than of a mean, petty, prejudicial outlook. The cultural elite’s much-loved phrase ‘the research shows’ is often a cover for a plain old moral crusade against what they judge to be deviant lifestyles. The elites, too, have a ‘skewiff’ understanding of basic social facts and alleged social problems, but they have the resources to doll up those skewiff views as knowledge-based judgements.

And the second thing to say about the idea that the public’s dumbness makes democracy difficult is that it is hilariously unoriginal. For as long as democracy has existed, even before it existed, in fact, elitists have bemoaned the herd’s lack of mental equipment for serious political engagement.

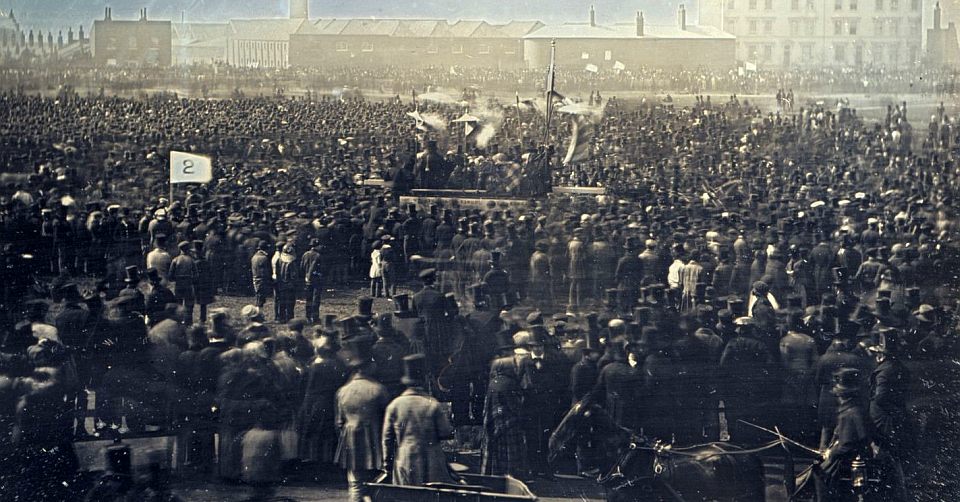

In the 1800s, in the discussion about introducing universal male suffrage in Britain, one observer said ‘universal suffrage could never be of great practical utility, unless bestowed upon a well-informed, intelligent public’ (1). In later debates in America and Britain about extending the franchise to blacks and women, the idea that these people were not intelligent enough to understand basic social facts was continually raised as a problem. As was said of women in early twentieth-century Britain, they ‘lack the expertise in naval, military, commercial, diplomatic and legal matters which is necessary for informed political activity’ (2). In early twentieth-century America, in his influential book Public Opinion, the elitist thinker Walter Lippmann bemoaned the ‘ignorance and stupidity [of]… the masses’, whom he described as a ‘bewildered herd’ whose investment with democratic authority over important political matters was bizarre. Today’s observers who are so achingly disappointed with democracy, or rather with the demos, have toned down the lingo; they’d never use a phrase like ‘bewildered herd’; but their handwringing over the British public being ‘wrong about nearly everything’ amounts to the same thing.

Ours is an era in which democracy is frequently and casually sneered at. Books like Bryan Caplan’s The Myth of the Rational Voter, whose front cover depicts the public as sheep, say ‘voters are worse than ignorant – they are irrational’. The New York Times, praising Caplan’s book, says it’s time we got over the myth about ‘the wisdom of crowds’, because in truth ‘[crowds are] often lousy at recognising their own self-interest’. One of the most striking things today is how much even the left-leaning sections of the cultural elites have accepted the idea that the irrationality of the vote-wielding mob makes democracy a difficult, if not forlorn task. It was liberal commentators who leapt upon the Ipsos Mori poll as hard evidence of public idiocy. Noam Chomsky’s famous phrase ‘manufacturing consent’ – the patronising idea that the media plant messages in the little people’s minds – comes directly from the work of Walter Lippmann. Today, we often see the dolling up in modern radical garb of yesteryear’s elitist sneering at the democracy-unready ‘bewildered herd’.

What is happening here is that a crisis of politics, a crisis of ideas, is being turned into a crisis of public intelligence. The failure of political parties and thinkers to come up with inspiring, future-orientated programmes for society is being projected back on to the herd, which is said to have ruined democracy with its skewiff views. In truth, the problem with democracy right now is not its participants, but its content – or rather its lack of content, its dearth of big, epoch-shaking thought experiments that might point society in a new direction and fire up a new era of political engagement. Unwilling to search their own souls and minds for new, enlivening democratic ideas, both the left-leaning and right-leaning elites turn viciously on the herd instead, laying the blame for the crisis of politics at the feet of a mob whom we should apparently never have invited into the democratic sphere in the first place.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

(1) The Crisis, 1832, edited by Robert Owen and Robert Dale Owen

(2) As summarised in Separate Spheres: The Opposition to Women’s Suffrage in Britain, Brian Harrison, Routledge, 2008

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.