Long-read

Dada and the making of modernity

Jed Rasula talks to Tim Black about the revolutionary artistic movement.

‘Zurich in February is deep into winter. The street has a dusting of fresh snow on accumulated layers that crunch underfoot; cheeks and noses of pedestrians glow in the mountain cold. In the old bohemian district, a block from the river that feeds into the lake from the north, the door opens at number one Spiegelgasse (Mirror Street: what a name), emitting a dense cloud of tobacco smoke. The year is 1916, and the place is Cabaret Voltaire.’

So begins Jed Rasula’s Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century, at Cabaret Voltaire, the site of Dada’s birth, on 5 February 1916. Or at least that ought to be the story. But, as Rasula explains in this stimulating, profound exploration of that most elusive of avant-gardes, Dada’s story is not linear. It’s a zig-zagging tale of cultural cross-pollination, a network of mutual inspiration, and often, antagonism. So even while Dada seems to begin in Zurich a century ago, with an anarchic cabaret, flush with poem readings, sometimes in three different languages simultaneously, masked plays, and modern-before-it-was-modern dance, in New York, two French emigres, Francis Picabia and Marcel Duchamp, have already been making proto-Dadaist waves since 1915, especially Duchamp (without his knowledge, as it turns out) with his Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2 (1912).

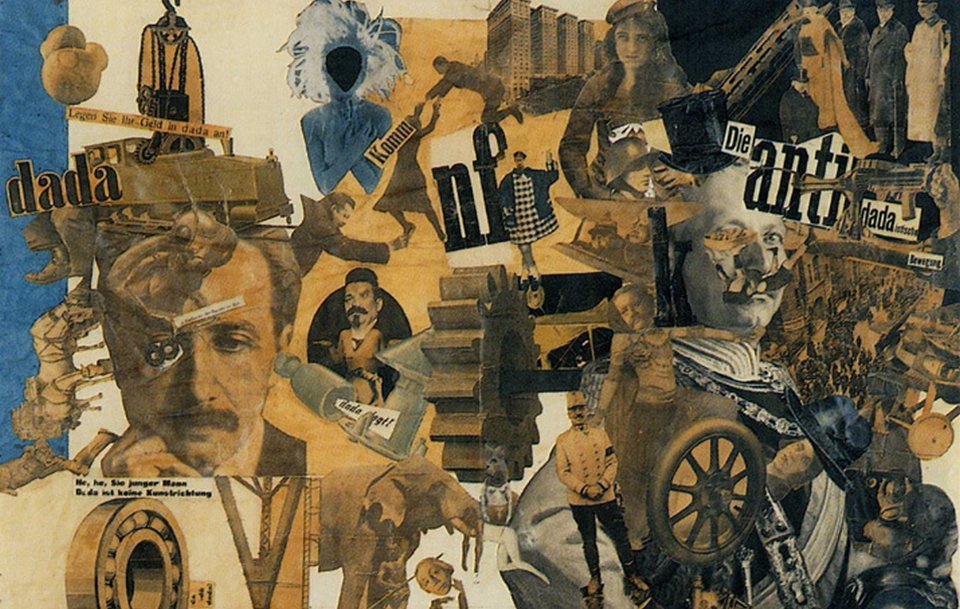

Dada’s geographical reach is astonishing. Thanks to one of the Cabaret Voltaire Dadaists, Richard Huelsenbeck, who moved back to his hometown of Berlin in 1917, a Berlin version of Dada soon explodes into absurd, venomous life, with the scathing photomontages of John Heartfield, and the equally scabrous, graffiti-inspired paintings of George Grosz its most prominent manifestations. If, as Grosz wrote, quoting Zola, ‘Hatred is holy’, then the Berlin Dadaists are its high priests. Even their Anglicised names are a kick to the ribs of German nationalism.

While Dada is burning ferociously in Germany’s imperial heart, the ground is simultaneously being laid for its explosion in Paris, with one of Cabaret Voltaire’s most animated of spirits, Tristan Tzara, a Romanian poet, evangelising the Dadaist anti-message, and winning the friendship and admiration of André Breton, who would later transform his Dadaist rite-of-passage into Surrealism. In 1920, ever the skilled publicist, Tzara promotes the founding Paris Dadaist event claiming that Charlie Chaplin is to be in attendance. As Rasula puts it: ‘On the day of the event a throng surrounded the Grand Palais, expecting to see “Charlot” himself, transfigured from movie star to Dadaist overnight. Once the crowd squeezed inside the venue, there was no mention of Chaplin; instead, the Dadaists read manifestos laced with the refrains familiar only to those informed of what had preceded this event in Zurich: “No more painters, no more writers, no more musicians… nothing, nothing, nothing.”’

Karawane (1916),

Karawane (1916),by Hugo Ball

That’s not a bad description of what Dada is and was. A huge, fat negation, with a smidgen of affirmation; or, as Grosz put it, a small Yes and a big No. Its practitioners weren’t Romantic-style artists, set apart from the throng by their creative genius; they were monteurs (mechanics) unravelling the comforting myths of Kultur. They turned against extant traditions and styles, scandalising the fine-arts establishment, and the hated bourgeoisie in general, with works made of everyday materials, not oil paint; pictures composed of cut-up newspaper clippings, not smooth lines and beguiling colours; inspiration drawn from the gutter, not the stars. It was radical, and destructive. It was Duchamp’s Fountain (the ‘readymade’ urinal which he signed with his pseudonym R Mutt). It was Max Ernst’s cork work. It was Hugo Ball’s nonsense-word poems. It was, as Tzara himself put it, ‘A virgin microbe that penetrates with the insistence of air into all the spaces that reason has not been able to fill with words or conventions’. And it was much more, too.

It’s never quite possible to pin Dada down and say ‘this is Dada’. Even the word, which means ‘hobby horse’ in French, and ‘yes, yes’ in Romanian, muddies rather than clarifies.

‘It’s because this question can’t be answered that Dada was so effective’, Rasula tells me. ‘Its participants could masquerade as almost anything. In Berlin it was momentarily taken to be a revolutionary upsurge with its own military force, thanks to the meltdown of imperial Germany at the end of the war and the ensuing political volatility. In Berlin it was presented more like a franchise, specifically as Club Dada, an advertising agency also offering counseling services on sex, among other things. By contrast, it was a relatively casual appendage for Max Ernst in Cologne and Kurt Schwitters in Hanover.

‘Tzara’s passage on the virgin microbe almost provides a definition, while remaining characteristically just out of the reach. It was Tzara above all who wanted to make a movement of it, and he even had stationery to make it official, carrying on a vast international correspondence that convinced people he was its leader. When he brought the microbe to Breton’s circle in Paris, he was received as the licensed operator of Dada. Paris was a world besotted with -isms and always ready for another, so it was only in that milieu that Dada’s profile as a movement took on a certain momentum and, by the same token, acquired an expiration date.’

That expiration date was 1923, when Tzara’s French acolytes grew tired of the man they were being urged to follow. Surrealism, and other stabs at novelty, soon followed, as one-time Dadaists struck out on their own. Still, in Destruction Was My Beatrice, Rasula calls Dada the ‘most revolutionary artistic movement of the 20th century’. But what makes it so special? Could the same not be said of Futurism or Cubism, which preceded Dada, or Surrealism, which comes after?

‘What made Dada outstrip the other movements was its functional anarchism’, Rasula explains. ‘Futurism and Surrealism made pledges, insisted on foundations, however loony they could be in their manifestos and activities. With Dada there was no central organiser (in contrast to the roles played by Marinetti for Futurism and Breton for Surrealism). Periodically there were lists published of all the Dada presidents, consisting not only of Dada participants but anybody who’d ever been in touch with a Dadaist or even attended a Dada event. This polyvalent aspect meant that Dada could arise anywhere and just as easily dissolve. It was present, forceful and volatile, but always on the verge of disappearing. It could even be retroactive, as in the case of New York Dada, much of which is dated to 1915, the year before Cabaret Voltaire was founded in Zurich – and the cabaret itself was underway for several months before the word “Dada” was discovered in a French dictionary. If revolutions are associated with organised force, Dada doesn’t qualify. But if force is understood as applying to that which is seditiously at hand, coming seemingly out of nowhere when the moment is ripe, then Dada was the most revolutionary of them all.’

A modernist modernity

Rasula is right to say that Dada did seem to ‘come out of nowhere’. But there was indeed plenty of cultural and emotional material ‘seditiously’ at hand. Dada, so creatively destructive, can almost be seen, then, as the eruption of impulses long latent in the socio-cultural subsoil of Europe – a sense of the world’s irrational rationality, its ‘disenchantment’ as a melancholy Max Weber put it. Existing artistic forms and tradition appeared to many late-19th-century and early-20th-century artists as inadequate, dead, ossified. Think of the God-forsaken abyss of Nietzsche, of Baudelaire and the French symbolists – all of whom informed Dadaist sensibilities – and think, too, of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s 1902 work of desolation, the Letter of Lord Chandos, in which a fictional poet explains why he can no longer write poetry. One of the ironies of all this is that the First World War, which many see as the prompt for modernist ruptures, breaks and cultural disillusion, was welcomed by many as the solution, a potential re-enchantment of the world, a chance to live (and die) for something.

‘What you’ve just said pretty much sums it up’, says Rasula. ‘An undercurrent of desperation dates back before the turn of the century, manifested in so many varieties of dissidence and repudiation. Disenchantment didn’t necessarily mean ennui. Sometimes it took the form of anarchism, a more principled disruption of social and political institutions. And in behaviour if not strictly by pledge, the Dadaists were anarchists.

‘But the Dadaists were individuals above all, and despite their riotous pledges of collectivity, they tended to go their separate ways. The agitation characteristic of the Berlin scene, Grosz recalled, was attributable as much to internal dissension as to any principled defiance of external affairs. The lifelong acrimony between Tzara and Huelsenbeck about the origin of the word Dada is symptomatic of the way personal ambitions could trump the collective.

‘Part of the ingenuity of Dada – making it seem more cohesive as a movement than it was – is its spirited indifference to normative codes of conduct. “They have given up the pretence of impartiality”, Ezra Pound shrewdly observed. But that didn’t mean their partiality came to the foreground: that would have simply been politics as usual. Rather, they practiced a spirited indirection, like planting false news reports, promising more than they could deliver, and leaving everyone unclear about what Dada was. Unlike so many other vanguard movements, it was a movement without a centre, and even today it’s hard for us to recognise activity that doesn’t emanate from a centre, a prime mover, a programme.’

Hugo Ball performing

Hugo Ball performingat Cabaret Voltaire, 1916

So how does Dada fit into the story of modernism in general? One of the most compelling, albeit broad-sweep, ways of looking at modernism is to grasp it as a response to the promise of modernity – the liberation of man from external sources of authority (church, king, tradition) and the concomitant development of individual autonomy – and the problems that promise throws up: the ‘God is dead’ groundlessness of subjectivity, of meaning in a world in which meaning/purpose is no longer given (by an authoritative tradition), a nagging sense of the illegitimacy of the modern self, of ‘angst’, and so on. Modernism, in this sense, could almost be seen as a polyvalent attempt to wrestle with the problems of modernity, to work through problems that the idea of autonomy throws up, to search for meaning in a ‘world abandoned by God’, as the young Georg Lukács described the modern novel’s raison d’être at about the same time as the Cabaret Voltaire was opening its doors.

The modernist answers to these questions are legion, of course. So Baudelaire throws himself into the maelstrom of the modern in Paris; TS Eliot self-consciously reaches out to a half-forgotten sense of tradition; Joyce, in Ulysses at least, reaches out to myth; others, from Impressionism to Expressionism, seek to excavate the interior, to turn self-consciousness and perception, subjectivity even, into the object to be represented.

Is it fair to say, then, that Dada is one of the most explosive of all these modernist moments? Rasula mention Dadaists’ ‘individualism’, and their ‘spirited indifference to normative modes of conduct’; so, I ask him, did they, in a sense, push through the promise of modernity, to the point of, well, absurdity?

‘I think each of the Dadaists would have a different perspective, though generally speaking they were enthusiasts of modernity. “Dada is the scream of brakes and the bellowing of the brokers at the Chicago Stock Exchange”, wrote Huelsenbeck, declaring Dada “the international expression of our times”. Grosz, Raoul Hausmann and Huelsenbeck embraced it in the form of America, home of the ultra-modern at the time; Picabia and Duchamp celebrated machine culture as a model for aesthetics, having discovered it in New York; Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber worked with Theo van Doesburg on the Aubette nightclub in Strasbourg, a thoroughly modernist design too advanced for the locals; André Breton tried in vain to convene a congress on modernism as a way of verifying the most advanced tendencies in the avant-garde.

‘Of all the Dadaists, Hugo Ball was the most wary of modernity, but in his diary he gave it the most sustained attention. Flight Out of Time is a mesmerising record of his struggle to confront modernity and figure out what was valuable in it without embracing it tout court. He was embarked on this before Cabaret Voltaire, so when Dada emerged he tended to regard it as one more ingredient in the configuration of modernism. He (like most of the other Dadaists) was captivated by the figure of the dandy as a quintessentially modern type of the “heroic aesthetes”. And he wondered whether Dada was “a synthesis of the romantic, dandyistic and demonic theories of the 19th century”.

‘Ball, like so many of his generation’, Rasula continues, ‘felt that the world of 1913 was totally suffocating, and at least initially welcomed the war as clearing the air. Robert Musil’s magisterial The Man Without Qualities revisits that prewar quagmire with exquisite deliberation. “No one knew what exactly was in the making”, Musil writes, “nobody could have said whether it was to be a new art, a new humanity, a new morality, or perhaps a reshuffling of society. So everyone said what he pleased about it.” I used this as the epigraph to an article called “Make It New” published in the journal Modernism/Modernity a few years ago. It captures that sense that the promise of modernity was inseparable from something like a gas leak, so there was always a danger of combustion, inciting the apocalyptic fantasies of Ludwig Meidner’s paintings, whose images routinely serve as book covers for titles on the Great War, though they all preceded it. What Ball discerned in modernity was prompted by Italian Futurist parole in libertà [words in freedom], actually: because “there is no language any more”, he surmised, “it has to be invented all over again. Disintegration right in the innermost process of creation.” Hence the birth of “wordless verse” at Cabaret Voltaire, the delivery of which triggered his final turn away from modernity altogether as he returned to the Catholic faith and retired to Alpine heights.’

Creative destruction

Many of the Dadaists may have been enthusiastic about modernity, especially its sky-scraping metropolitan form writ large in New York, but their attitude to modern ‘bourgeois’ culture and society was unremittingly negative. As Destruction Was My Beatrice records, Ball called Dada ‘a farce of nothingness in which all higher questions are involved; a gladiator’s gesture, a play with shabby leftovers, the death warrant of posturing morality’; and Grosz said ‘Dadaism was no ideological movement but an organic product that came into existence as a reaction against the cloud-cuckoo-land tendencies of so-called sacred art.’ During one Berlin Dada event, Grosz even mimicked pissing on to a painting by the then-esteemed Expressionist, Lovis Corinth. Dada always seemed to have a powerful destructive impulse, reacting against the warmongering hypocrisy of ‘bourgeois civilisation’ and, with it, the conventions of traditional art. But, I ask Rasula, was it different in Berlin? Is it true to say that in the work of Grosz or Heartfield, Dada developed a political, even utopian, dimension?

Toads of property (1921),

Toads of property (1921),by George Grosz

‘Apart from the innate darkness possessed by Picabia, it was in Berlin that the most violent appetites were unleashed. Much of it was just the temperamental aggressiveness of its participants, compounded by the political mayhem. Pent-up German orderliness, unleashed, fertilised Dada and revealed its teeth – or should I say fangs and claws? By comparison, those in the Zurich scene were Old School Romantic artists. The Berliners thought so, too.

‘As for Grosz and Heartfield, it’s hard for me to think of their work as utopian. They had such big targets on which to unleash their venom, from the collapse of Wilhelmine Germany and the rupture of the public sphere with contending parties ranging from the Freikorps to the conciliatory politicians who crafted the Weimar Republic, along with the tandem rise of Hitler. Grosz openly admitted his work was an expression of sheer hatred and revulsion. Heartfield was more politically oriented – and became a lifelong Marxist, even living in East Germany after the Second World War – so I suppose one might conceive of that as utopian, though he never produced anything like the agit-prop of the Soviet Union, or any positive images of utopian possibility. It was all witty denunciation in his photomontages.’

Should Dada be considered principally as a negative/negational force, then, subverting traditions, even attacking, as critic Peter Bürger put it in The Theory of the Avant-Garde (1974), the institution of art as it had hitherto been understood? A “big No”, as Grosz put it?

Ubu Imperator (1923),

Ubu Imperator (1923),by Max Ernst

‘Italian Futurism pioneered a “big No” before Dada, so if that’s the criterion for its success then it’s already second in line. I think the Dada dynamic is more accurately found in the Yes-No dialectic, a point emphasised by Marcel Janco later in his life. As I took care to indicate in my book, certain Dadaists emanated a darkly charismatic aura – Picabia and Tzara in particular – and this has skewed the overall reception. The Berliners were somewhat under the sway of Mynona’s concept of “creative indifference”, which is closer to Buddhism than to nihilism, and they found that an energising prospect: that is, creative adventure can embark on the slightest of provocations and with the most precarious of materials. So Kurt Schwitters’ rubbish collecting on city streets is a paradigmatic Dada act; and Hans Arp was more pantheistic than anything else. Arp and Schwitters were two of several Dadaists who got involved with Constructivism, which is antithetical to the subversive prospect you evoke. But, admittedly, Constructivism, in its initial Soviet form, pledged the dissolution of art as “a beautiful patch on the squalid life of the rich” as Rodchenko put it.

‘Bürger was adamant about the historicity of the avant-garde, and it’s important to remember how thoroughly all the scenarios in which Dada developed were laden with circumstance, with the Great War providing the initial event horizon, followed by the expansion of the vanguard into a momentarily fertilising postwar with utopian aspirations, before all too abruptly being thwarted by deteriorating global politics. So I’d quote Bürger here as offering a cautionary warning about the potential as well as the limits of negation: “Since now the protest of the historical avant-garde against art as institution is accepted as art”, he suggests, “the gesture of protest of the neo-avant-garde becomes inauthentic”. That’s harsh, but it’s a way of saying that the historical avant-garde confronted circumstances not readily analogised by or transposed to the present – or even the recent past.

‘There always seems to be nostalgia for certain glamorous phenomena, like the Lost Generation and the Beats, but nobody ever imagines these were sustainable or repeatable. That’s part of their allure. By contrast, Dada seems to insinuate continuation, a prospect I won’t deny, though I do think it can be too casually assumed or understood to repeat the original provocations. Hans Richter insisted it was “pointless to apply a shock effect that no longer shocks”, but it may be more accurate to suggest that Dada was closer to a joke, or a witty remark in a context in which it’s said you had to be there to get it.

‘The deadpan confrontation of the general public with patent absurdity, so characteristic of Dada, is not exclusively Dadaist. It was a characteristic of the Chat Noir in Belle Epoque Paris and typical as well of American humour (for example, Seinfeld and others) in our most recent fin de siècle. That’s the No of satire. But there’s a differently inflected confrontation more germane to Dada, I think, having to do with renunciation. I’ve recently been reading Ross Posnock’s new book, Renunciation: Acts of Abandonment by Writers, Philosophers and Artists, in which (surprisingly) Duchamp and Dada are mentioned only in passing. But Posnock elucidates the renunciatory gesture in a way that reveals it to be a nearly indispensable condition for the creation of art. He quotes Gilles Deleuze to the effect that “the painter does not have to cover a blank surface but rather would have to empty it out, clear it, clean it”; so there’s a primal iconoclasm against the very medium, and not something exclusively directed at social institutions. That’s close to Dada as well. Deleuze goes on to say (unquoted by Posnock) that “a whole category of things that could be termed clichés already fills the canvas, before the beginning”. Dada marks the advent of this awareness, and that’s part of what enabled photomontage and the general category of found objects to get underway. There’s no escaping the cliché, but that doesn’t mean it can’t be redirected.’

A joke that you had to be there to get; iconoclasm against the very medium of art; the consciousness of inexorable cliche… Such descriptions do get to the heart of the Dadaist moment. But at the same time, there’s always a nagging sense that what the Dadaists actually produced is eclipsed, lost to the theory of why it was produced. Does Dada’s importance lies less in its works than in its spirit? Or does that do Dada a grave disservice?

Fountain (1917), by Marcel Duchamp

Fountain (1917), by Marcel Duchamp‘The works themselves have gotten short shrift’, he answers, ‘even to the point of passing into art history as being of negligible value. It’s astonishing to me to consider how long art historians seemed indifferent to Max Ernst or Man Ray or Francis Picabia, all dynamos of visual adventure, conceptual ingenuity, and even Old School technical skills, to say nothing of the extraordinary collage work of Hannah Höch, Hausmann, and Heartfield, or the sculpture of Hans Arp. But the Dadaists programmatically resisted the major media of the beaux-arts tradition, so they were taken to be less serious somehow. Certainly not in competition with the likes of Picasso or Matisse.

‘Grosz’s ferociously satirical drawings were inspired by graffiti, deliberately meant to resemble the products of idiots and children they were accused of being. So it took nearly a century for the art world to begin to appreciate Dada art as art. Another factor in the delay was the rising eminence of Duchamp, whose anti-retinal, conceptual art suggested that everything done by the Dadaists counted only as thought, not product. And yet another factor that further compromised the reputation of Dada art is that much of it was not only made of ephemeral material, but it was lost or destroyed. So key works by Man Ray, Duchamp and Hausmann were authorised reconstructions of vanished artworks.’

Aftershock

Dada seemed to emerge at the same time as another art form, long denigrated by a classical tradition, took off, namely, jazz. Is there a relationship between the two?, I ask.

‘Pure coincidence, fortuitous synchrony. The two words began to circulate at the same time (in Europe, anyway), and were sometimes confused. “Jazz” was very loosely understood at first. In Britain, “the jazz” was thought to refer to a drum set, a novelty apparatus at that time. In France and Germany, it was understood as a particularly boisterous style of performance. In America it meant novelty music, or music played with extra-musical effects and weird instruments (like the saxophone, a 19th-century invention almost unknown until the 1920s). So with this sort of semantic slippage, it’s not surprising to find another slippery term, Dada, conflated with it. In 1917, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band first recorded, thereby launching the word “jazz” into the public sphere, where it was soon being used in posters advertising Dada events. Sometimes they mentioned dances as well, a reminder of the fact that Hausmann, Grosz and Schwitters were keen on the latest dances, inevitably American, and therefore more and more linked to jazz.

‘The African-American novelist Ralph Ellison, trying to place the significance of Minton’s Playhouse for the bebop revolution of the 1940s, imagined it “is to modern jazz what the Café Voltaire [sic] in Zurich is to the Dadaist phase of literature and painting”. In fact, the main difference between European and American responses to jazz (apart from the historical fact that jazz derives from racially denigrated Americans) is that the avant-garde was a pervasive phenomenon across Europe when jazz erupted late in the Great War. Giving “free play to the spontaneous manifestations of the subconscious” was a goal shared alike by jazz musicians and the avant-garde, Robert Goffin suggested in his 1944 history Jazz from the Congo to the Metropolitan, citing Blaise Cendrars, Guillaume Apollinaire, James Joyce, Giorgio de Chirico, René Magritte, Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí to make his case. Later, the English historian Eric Hobsbawm (who wrote on jazz under the pseudonym Francis Newton) made the same point: in Europe, “jazz had the advantage of fitting smoothly into the ordinary pattern of avant-garde intellectualism, among the Dadaists and Surrealists, the big-city Romantics, the idealisers of the machine age, the Expressionists and their like”. It could be a two-way street, however. The composer Hoagy Carmichael, living in Indiana where he was a friend of jazz trumpeter Bix Beiderbecke, heard about Cabaret Voltaire from a friend who’d spent the war in Switzerland, and he decided that jazz and Dada were cut from the same cloth. Certainly they were both widely recognised as pranks, spirited animations of youthful folly, both of which were nonetheless perceived as actual threats to the body politic.’

Jazz may have only a coincidental relationship with Dada, but there is much in 20th- and 21st-century culture that seems to draw more consciously on the legacy of Dada, be it Andy Warhol or the voguish idea of mash-ups. But Rasula is not convinced the virgin microbe of Dada is alive and well today.

‘Because I’m disposed to think of Dada historically’, he says, ‘I tend to be wary of the urge to detect traces of Dada persisting in the present. Obviously, anything from the past is a provocation to the present, even if you don’t happen to know of it. More and more, I think, with the awareness of Dada enhanced by the simple fact of a centenary, people will be startled to see that seemingly contemporary phenomena (like mash-ups) have an historical pedigree, and that’s fine. But the urge to see a resurrection of any historical phenomenon is misplaced.

‘The primary continuity from Dada to now has been so commercially filtered that it probably should be discounted: and that is, the disruptive, asymmetric, or otherwise disarming, presentational strategies in print culture and in the arts. Whenever you encounter something you don’t expect it brings a whiff of Dada. Wherever the printed ad tilts or blurs and challenges your ability to process it instantly, Dada hovers nearby. Commerce has absorbed any and everything, including Dada, but it’s pointless to conclude that it was always complicit in advance.

‘Where other avant-garde movements fancied oppositional strategies meant to depose or displace reigning institutions and social mores, Dada was more like a guerrilla tactic undertaken by an extremely outnumbered and loosely bound group. That made it easier for it to masquerade as an institution in and of itself – a kind of utopian mockery – and also easier to subside without any attendant sense of failure or frustration. Its spirit is nicely captured in a quote from Hugo Ball that I used to end my book: “Let us be thoroughly new and inventive. Let us rewrite life every day.”’

Jed Rasula is a professor of English at the University of Georgia. He is the author of many books, including: The American Poetry Wax Museum: Reality Effects, 1940-1990 (1996); Hot Wax, Or, Psyche’s Drip (2007); Modernism and Poetic Inspiration: The Shadow Mouth (2009); and This Compost: Ecological Imperatives in American Poetry (2012).

Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century, is published by Basic Books. (Order this book from Amazon(UK).)

Tim Black is the editor of the spiked review.

Picture by: Wikimedia commons.

In-article picture credits:

Toads of property; picture by Austin Kleon, and published under a creative commons license.

Ubu Imperator; by The Artchive.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.