Why is the left pushing this hate-crime panic?

It’s as dubious as the ‘black mugger’ moral panic of the Seventies and Eighties.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

The Home Office this week reported an unprecedented 29 per cent annual rise in hate crimes in England and Wales. A barrage of condemnations and outraged questions followed. Why, demanded Labour politicians and media pundits, were the Tory government and the police not doing more to combat the ‘unacceptable’, ‘soaring’, ‘surging’ and ‘record’ rates of hate crimes? The Labour-backing New Statesman magazine asked ‘Will Brexiteers finally admit the EU referendum caused hate crime?’.

There is, however, another set of pressing questions, which few seem keen to ask. Why do so many now uncritically accept the Home Office’s claims about a boom in racist and Islamophobic hate crimes? Why do the sort of radicals who rejected the British state’s past exploitation of dubious crime figures now take the same state’s hate-crime stats at face value?

In short: why do those who would have rubbished the Home Office/police ‘black mugging panic’ of recent history seem so keen to endorse the hate-crime panic today?

There should be little doubt that the talk of ‘soaring’ rates of hate crime is a panic, based on highly questionable evidence. The Home Office report claims that a 29 per cent increase reflects ‘both a genuine rise in hate crime around the time of the EU referendum and the Westminster Bridge terrorist attack, as well as organisational improvements in crime reporting by the police’. In other words, the authorities concede that the ‘genuine rise’ is not as big as the headline figures suggest.

But the problems go much further than that. First, exactly what is a ‘hate crime’ anyway? The emotive label conjures images of serious and violent offences. Yet most of these recorded hate crimes are not what would normally be considered crimes at all. They are alleged incidents, many of them verbal, reported to the police, often through phone, email or social-media hotlines. They are not investigated by the police, far less tried as crimes in a court of law.

Instead the police simply record every report as an official hate crime without any need to question or investigate at all. The operational guidance for police forces spells it out: ‘For recording purposes, the perception of the victim, or any other person, is the defining factor in determining whether an incident is a hate incident… The victim does not have to justify or provide evidence of their belief, and police officers or staff should not directly challenge this perception. Evidence of hostility is not required for an incident or crime to be recorded as a hate crime.’ (My emphasis.)

So, unlike other crimes, if anybody at all says anything at all is a hate crime, the police must record it as one, no actual ‘evidence of hostility’ required or questions asked at all. Given this subjective system, and the way that the Metropolitan Police and mayor of London made high-profile appeals for the public to report any whiff of hate crimes after the referendum and terror attacks, the real surprise might be that the recorded total increased by only 29 per cent.

Away from the headlines about a ‘surge’ in recorded hate crimes, other official statistics released with rather less fanfare suggest a slightly different story. The Crown Prosecution Service’s annual report for 2016/17 shows a sharp decrease in both the number of religious and racial hate incidents that were referred on to the CPS by the police, and the number taken to court. One of the few bloggers to cast a more critical eye over the official figures reports that police referrals dropped by 21.9 per cent, while prosecutions were down by 7.89 per cent.

In other words, despite the overall increase in recorded hate crimes, the police decided far fewer of them were worthy of being passed on for the CPS to consider criminal charges against the alleged offenders. And the CPS in turn ruled that even fewer offered a serious enough prospect of conviction to merit taking them to court. This is apparently the fourth successive year that the total of police recorded hate crimes has gone up, while police referrals to the CPS have gone down.

No doubt some will claim this fall as proof that police and prosecutors are not taking hate crimes seriously enough. They might well have had a point in the not-too-distant past. Today, however, the authorities are falling over themselves to be seen to be doing the right thing on race hate. If there is a chance of getting alleged racists and Islamophobes into court and prison, the police and prosecutors grab it with both hands to advertise their ethical credentials. But in most instances, they have not got a case.

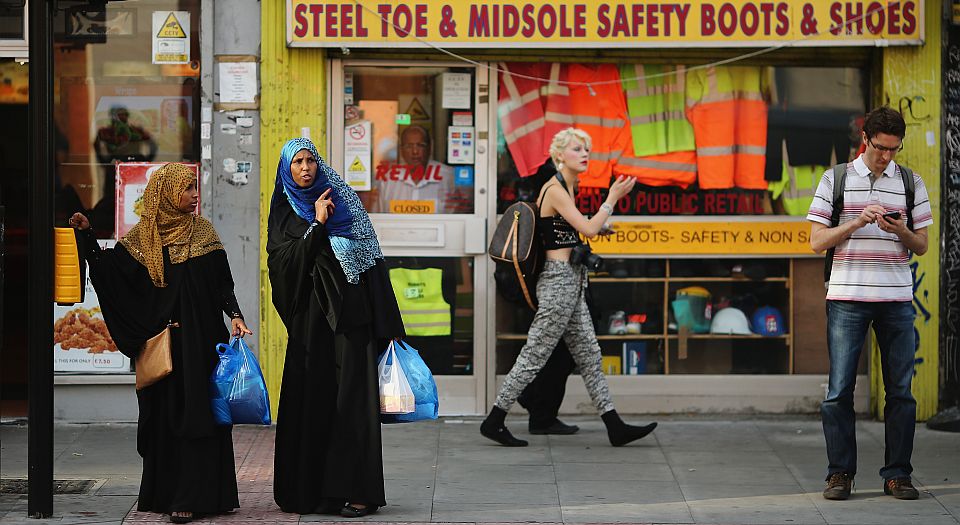

The closer you look, the more the hysteria about ‘soaring’ hate crimes resembles a classic, state-driven law-and-order panic, exploiting dubious crime statistics to justify more authoritarian measures. The consequences are to demonise one section of the population – in this case, the allegedly racist, Islamophobic white working classes – while striking fear into others and potentially stoking divisions.

Yet Labour politicians and radical commentators have enthusiastically endorsed the hate-crimes scare, only complaining that the Home Office and police need to take even firmer action. This contrasts starkly with the 1970s and 1980s, when the left mounted a powerful critique of the British state’s promotion of a scare about ‘black muggers’.

In 1972 the British media reported the arrival on our city streets of ‘a frightening new strain of crime’ – mugging. This was implicitly and often explicitly understood to mean street robberies by young black males. The Tory home secretary told the House of Commons that, in London alone, ‘muggings’ had increased by 129 per cent over the previous four years. The crusade against ‘black muggers’ became the pretext for a sustained racist crackdown on black youth in inner cities.

From the start, the mugging scare was challenged by radical writers and campaigners as a got-up ‘moral panic’ targeting black communities, based on invented and inflated crime statistics. In 1978 radical academics led by sociologist Stuart Hall published the classic work Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. Policing the Crisis situated and critiqued the ‘black mugger’ panic in the context of the racially loaded law-and-order politics of the age.

Today, any such critical attitude towards the UK state’s moral panic about hate crimes is noticeable by its absence. Instead opposition politicians and radical commentators have effectively become cheerleaders for the panic. Why? Because it suits their Brexit-bashing political agenda to pigeon-hole white working-class Leave voters as violent racists and Islamophobes, whose ‘unacceptable’ ideas need to be policed into submission.

The result is that these self-styled radicals now end up on the same side as the state, demanding even more police and CPS action to curb ‘hate speech’, aka free speech, on everything from Islamic terrorism to immigration. At a moment when British society is more tolerant and less racist than in living memory, supposed anti-racist campaigners demand more official intolerance and the demonisation/criminalisation of a section of society. That turnaround really ought to be deemed ‘unacceptable’.

Of course there are some real racist crimes in our society – just as, in the past, there really were some street robberies carried out by black youth. That does not alter the politically driven character of these panics. Then, every back inner-city youth was looked upon in fear as a potential mugger. Now, every suburban white youth is being looked down upon with similar dread as a potential race-hate criminal. Both are expressions of bigotry; the current scaremongers are effectively playing a new version of the race card.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His new book, Revolting! How the Establishment is Undermining Democracy – and What They’re Afraid of, is published by William Collins. Buy it here.

Picture by: Getty

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.