Trigger warnings are educational suicide

Taking Durkheim's Suicide out of schools is madness.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

One reason I and many of my friends were drawn towards the discipline of sociology is because it helped us confront and understand many of the disturbing dimensions to everyday life. At its best, sociology gives meaning to what we perceive as private troubles, and allows us to understand those troubles within a comprehensible pattern of social interaction. So I am horrified by the argument being used by AQA, the largest exam board in the UK, to justify dropping the theme of suicide from its A-level syllabus.

AQA defended its decision on the grounds that a subject as disturbing as suicide posed a serious risk to the mental health of A-level students. Rupert Sheard, AQA qualifications manager, said his organisation has a ‘duty of care to all those students taking our courses to make sure the content isn’t going to cause them undue distress’.

But any version of sociology that does not disturb or distress people has little to do with the serious study of society. According to AQA, sanitising and impoverishing the sociology curriculum is a small price to pay for insulating 17- and 18-year-olds from disturbing aspects of everyday life. How long before A-level students are handed smiley-face stickers and offered a happiness sociology curriculum? If the teaching of sociology has to be reconciled with the supposed emotional disposition of students, then the integrity of the discipline becomes a negotiable commodity.

The argument used by AQA suggests young people studying A-level sociology should be regarded as patients rather than students. Good teachers have always sought to encourage students to feel good about the subjects they were studying. But teaching the knowledge content of a subject was always seen as the main mission of educators. According to AQA, however, it seems that subject content is subordinate to the alleged health risks posed by a discussion of suicide.

AQA’s decision to infantilise A-level students is the 21st-century equivalent of the traditional moral regulation of the education of young people. The classic exhortation, ‘Not in front of the children’, has been reconfigured as an exercise in therapeutic management. Traditional moral regulation has been displaced by the imperative of medicalisation. Ironically, the discipline of sociology – which has done so much to bring to light the moralising impulse driving the medicalisation of social life – has itself been medicalised.

AQA’s decision to remove suicide from the curriculum shows the extent to which education has fallen under the influence of therapeutic culture. Since the turn of the century, the desire to put up a moral quarantine around uncomfortable and distressing themes has been gaining momentum. A decade ago, I criticised a memorandum calling on academics at Durham University to obtain approval from an ‘ethics’ committee before they gave lectures on certain ‘distressing’ subjects, including abortion and euthanasia. At the time I received numerous emails from colleagues who were astonished by this illiberal incursion on academic freedom.

That was then. Over the past decade, numerous universities have introduced codes of conduct telling academics to ‘mind your language’, or urging them to ‘try to be sensitive to the feelings of others in the use of language’. The most frightening symptom of this medicalisation of the classroom is the introduction of so-called trigger warnings in higher education. In some North American universities, course handouts include trigger warnings about reading material. Novels and poems, which university students have read for centuries, are now assigned a health warning to indicate that they contain scenes of domestic violence, sexism, racism or a variety of other pathologies.

The premise of the trigger-warning crusade is that students cannot be trusted to engage with uncomfortable subjects. Nor can they be allowed to judge for themselves how to interpret difficult and challenging experiences and practices. Unfortunately, this attempt to quarantine the uncomfortable and dark dimensions of the human experience only serves to diminish education.

The emptying out of education

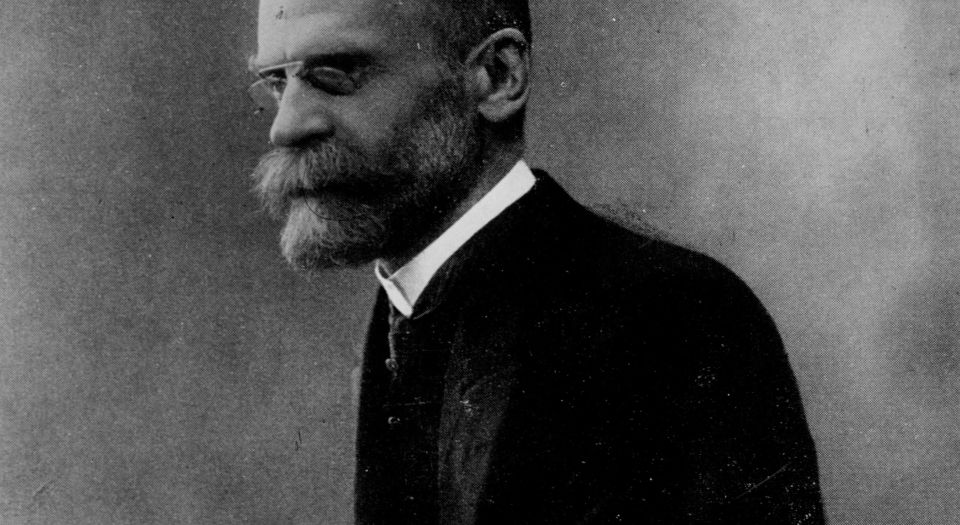

It is frequently suggested that the adoption of a pedagogy oriented towards therapeutic values need not encroach on the integrity of education. However, the subordination of education to therapeutic values does not leave the integrity of subject knowledge untouched. AQA’s decision to ‘protect’ students from a difficult subject like suicide is a case in point. Suicide is not just a peripheral issue for the discipline of sociology. One of sociology’s founding texts – Suicide (1897), by Emile Durkheim – is now represented as a potential risk to students’ wellbeing.

For sociologists, Suicide is not just another book. Rather, it offers a pioneering example of what the discipline of sociology can accomplish using a rigorous methodology and statistics. For almost a century, Suicide has been the text through which sociological concepts and methods were introduced to students. Getting rid of the treatment of suicide by Durkheim is like dropping the study of the Holocaust from twentieth-century history.

If the theme of suicide can be excised from the sociology curriculum, what happens to uncomfortable issues like racism, the oppression of minorities, exploitation, rape, domestic violence? There is an endless range of sociological topics that could trigger powerful emotions among sociology students. And why just focus on sociology? Will curriculum engineers now shift their focus to religious studies and quietly drop the Bible? After all, what could be more traumatic than a text in which fathers kill their sons, people indulge in ethnic cleansing, and suicide and rape are common. The Bible is far more haunting than the dry statistics contained in Durkheim’s Suicide. When the attempt to transform the classroom into a distress-free zone becomes widely accepted, the content of education becomes subject to criteria external to education.

The pedagogic strategy of treating students as if they were patients does students no favours. It deprives young people of the opportunity to develop the moral and intellectual resources they need to engage with challenging issues. Students are prevented from working out for themselves how to deal with issues like suicide. Instead of cultivating teenagers’ moral and emotional independence, therapeutic education reinforces their passivity and sense of powerlessness. Yes, some issues are distressing. But distress is not an indicator of illness; it is an integral part of people’s existence. When feeling distressed is medicalised, young people are prevented from developing their own ways of coping with painful experiences.

Neither teachers nor therapists can second-guess the reaction of young people to difficult themes or issues. Whether the content of a particular text causes distress to a reader cannot be worked out in advance, according to a pre-existing formula. Instead of turning sociology into an exercise in sensitivity training, educators should be encouraging students to gain a sociological understanding of their predicament. Compassion and thoughtfulness, not the avoidance of difficult topics, is the way forward.

As a discipline, sociology is in the business of questioning comfortable assumptions. In doing so, it frequently draws attention to the dark and destructive passions prevalent in human society. At its best, sociology really does disturb students, and force them to engage with some very uncomfortable realities. If AQA wants to turn education into a distress-free zone, it might as well stop offering sociology A-levels altogether.

Frank Furedi is a sociologist and commentator. His latest book, First World War: Still No End in Sight, is published by Bloomsbury. (Order this book from Amazon (UK).)

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.