The real ‘spaghetti monster’ is campus censorship

It's not just faith-baiting atheists who are under attack from Britain’s ban-happy students' unions.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Anyone familiar with the New Atheism movement will be familiar with the supposedly hilarious comparisons of the idea of a god to that of a ‘flying spaghetti monster’. In the same way that it is impossible to disprove the prospect of a god, it is also impossible to disprove the existence of a ‘flying spaghetti monster’. Ergo, the onus to prove the existence of an all-mighty supreme being lies with those proposing it. Observe any debate between the partisans of New Atheism and their religious opponents, and soon you will encounter this argument being wheeled out, with the usual self-satisfaction of Dawkinites. This rhetorical device, along with other roughly-correct-but-tired clichés, forms a central part of the lexicon of the New Atheism movement.

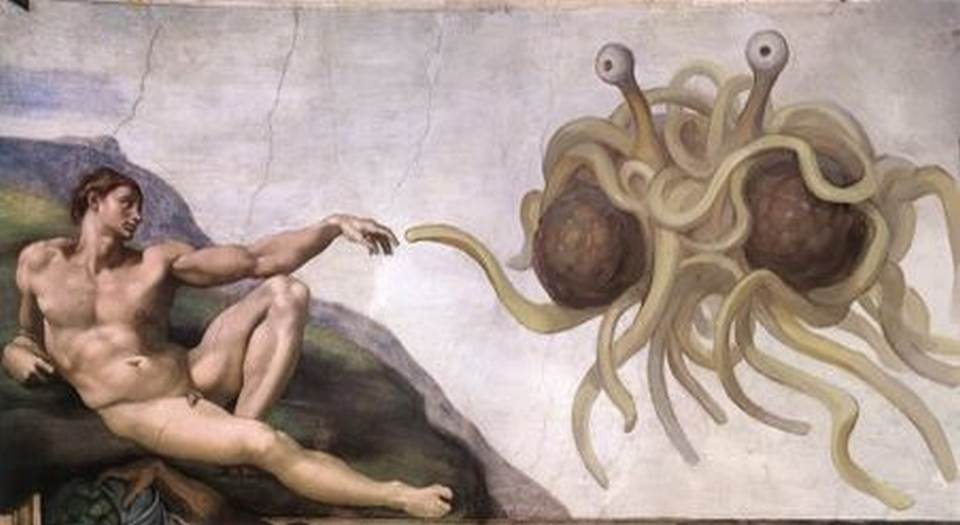

So it was only to be expected that the spaghetti monster would find itself being used as an advertisement by a group of students united in their lack of belief, the South Bank University Atheist Society. As a design for a poster, the society decided to replace the image of God in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco, The Creation of Adam, with the image of a spaghetti monster.

As has become an all-too-familiar occurrence in recent years, the big wigs of the students’ union swung into action, resulting in the poster being removed and the Atheist Society being banned from a start-of-term student event. Originally, the society was told the ban was due to a shame-free Adam bearing his bodily all in the poster, as shown in the original image in that great den of licentiousness, the Vatican. However, the students’ union soon changed its mind and decided it was the edited part of the poster – the replacement of God with spaghetti – that was the cause of offence.

The case is similar to the incident at the London School of Economics (LSE) freshers’ fair last year, in which a group of atheist students decided to don t-shirts depicting Jesus and the prophet Muhammad in cartoon form. University officials forced students to cover up the offending images, citing religious offence.

Both cases are similar in that they are both instances where claims of religious offence have led to censorship. The supposed right of certain, seemingly unidentified students not to have their religious sensitivities offended has trumped the right of groups of atheist students to wear moderately funny t-shirts or display unfunny posters – a trampling of their freedom of expression. In both cases, the authorities eventually reversed their decision after an outcry.

However, there is another similarity. Both these cases involving an infringement of freedom of expression in the name of religion have been taken up by certain big names. Ever itching for a fight with religion, certain public figures will furiously tweet about the injustice of it all, write a blog or opinion piece, and proclaim boldly (and correctly) that ‘no one has the right not to be offended’.

However, these acts of censorship at universities are not taking place in isolation. Banning and censoring has become an all-too-common occurrence on university campuses. Since September 2013, beginning with the Edinburgh University Students’ Association, roughly 20 students’ unions have banned the summer hit ‘Blurred Lines’ by R&B singer Robin Thicke from being played in union facilities, on the grounds that its lyrics are sexist and offensive. Likewise, over 30 universities have banned the sale of the Sun newspaper on campus due to its Page 3 feature, where buxom young women bare their breasts.

While bans and acts of censorship on the grounds of religious offence are not justified, they are based on the idea that if something is offensive – actually or potentially – to certain segments of the student population, then it can rightfully be banned. Bans, whether on the basis of religion or sexism, are based on intolerance, an intolerance of certain things that some people may find objectionable, distasteful, uncouth or offensive, and which in turn compels them to be censored – whether it is Robin Thicke’s lewd lyrics or Photoshopped frescos.

Yet the faith-bashing warriors who raged against the censoring of t-shirts at the LSE and the censoring of a poster at South Bank University will, for the most part, have little to say about the wider culture of bans and censorship at universities. The banning of the spaghetti-monster poster at South Bank is not a creeping resurgence of intolerant religion or a capitulation to Christian complainers by university officials. Rather, it is part of an increasingly intolerant climate at universities in which offence, religion-based or otherwise, is deemed a legitimate ground for something to be banned. Were it not for this nexus of intolerance and offence-taking at the modern university, the spaghetti-monster poster would have survived.

Tom Bailey is studying for a masters in history at University College London. Visit his personal website here. Follow him on Twitter: @tbaileybailey

Picture: Wikimedia Commons

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.