The NCCL was right to affiliate with PIE

If civil liberties groups won't defend free speech for

the unpopular, what's the point of them?

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

To see the parlous state of moral and political debate in twenty-first-century Britain, look no further than the Harriet Harman / PIE scandal.

Here, in this resuscitation of old claims and smears about the relationship between the National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL) and the Paedophile Information Exchange (PIE), we had an opportunity for a serious debate about freedom of speech and association, about whether even the most unpopular groups in society – and what could be more unpopular than an organisation of self-defined paedophiles? – should have the right to exist and to give voice to their ideology.

But instead, we’ve ended up with yet another shrill clash of competing paedo smears, with the Daily Mail suggesting that Harman (who was legal officer of the NCCL from 1978 to 1982) was a friend of perverts, and Harman’s backers in the press countering that actually it’s the Daily Mail that ‘sexualises children’. All matters of principle in the old NCCL / PIE relationship have been brutally elbowed aside by every side in this smear-fest disguised as a debate, where the national sport of ‘Hunt the paedo’ has trumped measured discussion of rights, freedom, and unpopular causes.

You’d never know it from the media frenzy, but there are some important principles at stake in this flashback to the old ties between the NCCL and PIE – primarily the principle that even the most unpopular people in a society should be free to associate with each other and to propagate their ideas and advocate for legal change. No, not free to abuse children or plan to abuse children, as some individual PIE members were arrested for doing, but free to express an outlook, however warped that outlook might appear to the rest of society.

The truth is that the NCCL was right both to have PIE as an affiliate and to defend its members against charges of ‘corrupting public morals’. Why? Because a key role of any civil liberties group worth its name is to defend the rights of association of the most loathed sections of society, to ensure that even the profoundly unpopular enjoy the same liberties, most importantly freedom of speech, as the respectable and the right-on.

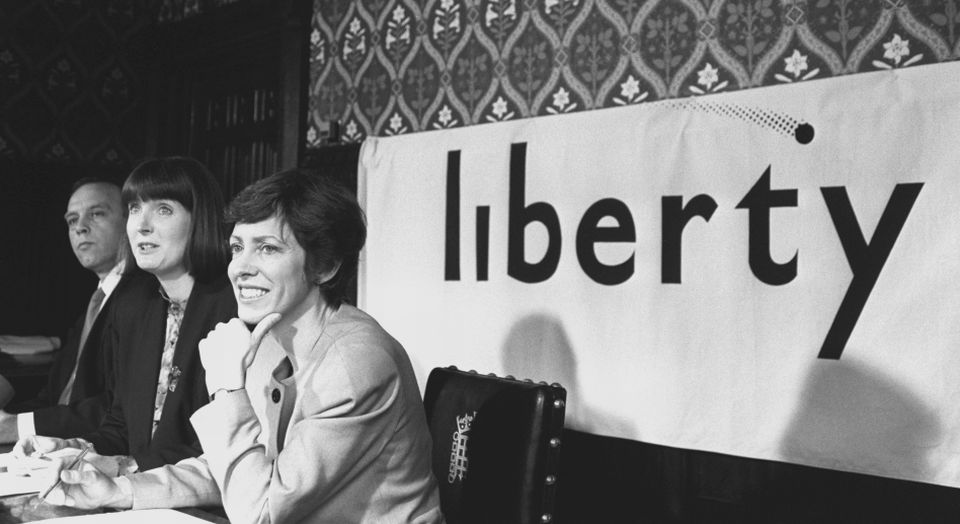

For all its faults, the NCCL of the 1970s and early 1980s was a pretty good civil liberties organisation, certainly in comparison with the aloof, lawyerly outfit it has become in recent years under its new name of Liberty. Indeed, its willingness to have PIE as an affiliate, and to defend its members against the ‘crimes’ of publishing a non-pornographic magazine and posting private letters to each other containing sexual fantasies, shows just how serious it was about civil liberties, and that it possessed that key belief that should motor all defenders of freedom – that the freedoms of speech and association are universal and must extend even to those we hate or simply do not understand.

Reading the smearing articles about Harman – and also Patricia Hewitt and Jack Dromey, two other Labour bigwigs who were leaders of the NCCL when it had PIE as an affiliate between 1975 and 1983 – you could be forgiven for thinking that the NCCL had helped to facilitate actual acts of paedophila. It didn’t, of course. What it did was protect the freedom of individuals to promote the idea of paedophila and to define themselves as an association of paedophiles. And anyone who truly believes in freedom of thought and speech must, as an absolute bottom line, appreciate the fundamental moral difference between acts and ideas. Acting on paedophilic thoughts is a crime, as some PIE members discovered; having and voicing paedophilic thoughts is not, or at least shouldn’t be. There is a profound difference between breaking the law against child sex and campaigning for a change in the law on the age of consent, however perverse the reasoning for that campaign might seem. It is to the NCCL’s credit that it recognised this.

The NCCL’s involvement with PIE consisted primarily of defending its right to propagate its ideas and to exist as an organisation. It did not fight for the ‘right’ of PIE members to rape children, but rather defended PIE’s right to lobby, to publish a magazine with paedophilic ideas, to advocate for the abolition of the age of consent, and to post private letters to one another describing fantasies. Incredibly, some PIE members were actually arrested for doing that, for ‘sending obscene material by mail’ by writing personal letters to one another that were not publicly disseminated. If you do not recognise that as a pretty tyrannical assault on freedom of thought, then you need to go back to school and retake Liberty 101. The NCCL’s defence of PIE’s right to exist and its right to share ideas and information was correct and admirable.

If civil liberties organisations won’t defend the freedoms of speech and association of unpopular groups, then what is the point of them? Respectable groups don’t find their freedoms curtailed. The Women’s Institute is not prevented from publishing its ideas; Labour Party members aren’t arrested for what they write in private letters. It is only the moral outliers of a society who have their right to propagate their beliefs hammered by the authorities, whether it’s gay pornographers, the hard left, Nazis or self-confessed paedophiles. It is the freedom of speech of these deeply unpopular causes that true civil libertarians must defend, firstly because we recognise that freedom of speech means nothing unless it extends to everyone; and secondly because if we allow the state to define a certain outlook as so foul that it ‘corrupts public morals’ and thus must be extinguished, then we set a very dangerous precedent that might one day reach to us and call into question the acceptability of the views we hold, too.

In the US, where there is a far healthier attitude to freedom of speech, civil libertarians have for a long time asserted that it is entirely possible to defend a group’s right to exist, speak and publish (not to abuse, I reiterate) while simultaneously finding what that group says to be outrageous and grotesque. So the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has defended the right of American Nazis to hold a march in a predominantly Jewish town – not because it likes Nazis (some of the ACLU’s leading figures are Jews whose forefathers were obliterated in the Holocaust) but because it recognises that a serious commitment to political freedom means defending it even for the ‘enemies of freedom’.

Indeed, the ACLU has also defended the speech and association rights of paedophilic groups. In a court case in the early 2000s, it represented the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) in a civil suit in which the association was being sued by the parents of a 10-year-old boy who was raped and murdered by two paedophiles. The parents claimed NAMBLA’s (non-pornographic) website fuelled the outlook of the two paedophiles. The ACLU argued that there was no evidence to back this up and defended the right of NAMBLA to continue publishing its ideas and campaigning for the abolition of the age of consent.

Why did the ACLU do this? Not because it is pro-paedophile, of course, but because it is pro-freedom of thought – consistently and seriously. It recognised how extremely unpopular NAMBLA is; in her book Free for All: Defending Liberty in America Today, Wendy Kaminer, a leading member of the ACLU at the time of the NAMBLA case, and today a contributor to spiked, said ‘virtually no group of people is more unpopular’ than paedophiles and revealed that ‘the ACLU [was] excoriated by many and lost considerable support’ over its decision to defend NAMBLA. But it was the right thing to do, she wrote, because a ‘simple appreciation of freedom of thought and expression’ should make it clear that we must have freedom even for ‘offensive, unpopular speech’.

‘The notion that pubescent or prepubescent children may enter into consensual, mutually beneficial sexual relationships with adults seems deeply flawed to me, but so do a lot of ideas I don’t share’, wrote Kaminer. If libertarians ‘only protected sensible speech, we’d inhabit a very quiet nation indeed’, she said. That, right there, is a principled commitment to freedom of thought and expression, where it is recognised that even ideas we find flawed or foul should not be censored, and the groups who espouse them should not be broken up. The NCCL once took a similar Voltairean approach to freedom of speech and organisation, and it is now lambasted for doing so.

There have been two responses to the return of the NCCL / PIE scandal: the illiberal side says the NCCL was disgusting and crazy; the other, pro-Harman side is little better, saying, ‘Look, the Seventies were weird and sexual liberation went too far, so you can’t blame the NCCL for stupidly having PIE as an affiliate’. Both sides avoid the question of principle, the question of whether – regardless of PIE’s perverted ideas and massive unpopularity – it was right for civil libertarians to defend its right to exist and to speak and organise. The fundamental thing that was different in the Seventies was less the out-of-control sexual liberation stuff than the fact that civil liberties groups genuinely believed in civil liberty. It is the ditching of that core commitment to freedom in recent years, not least by Liberty itself, which means so many can now look back in horror at the fact that libertarians defended the right even of paedophiles to publish words and arguments. The coming back to life of the NCCL / PIE scandal really confirms how alarmingly illiberal, how disconnected from true freedom of thought and Voltairean ideals, modern Britain has become.

It’s easy to have a pop at Harriet Harman, even easier to mock the Daily Mail for being hypocritical. But that’s enough easy posturing. Let’s now ask some hard questions. Do you support the right of paedophiles to set up an organisation (no, not a child sex ring, but a campaigning organisation)? Do you support the right of paedophiles to publish their ideas and their written fantasies? Do you support the right of paedophiles to campaign for a reduction in the age of consent? Do you support these rights even though you find the content of the material being published and the arguments for a lower age of consent to be deeply immoral and perverse? I answer yes to those questions. How about you?

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.