The EU’s culture war against the people

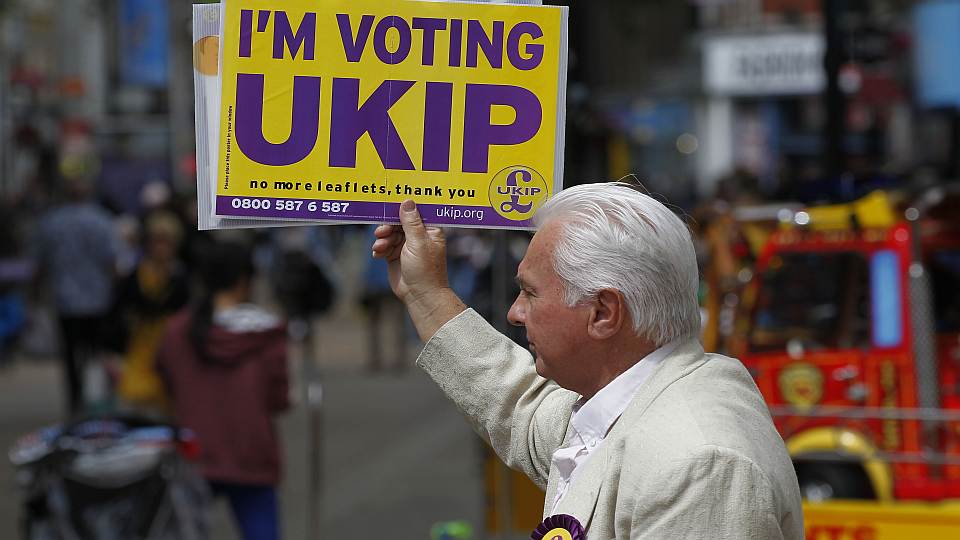

Populist movements like UKIP expose the EU’s estrangement from everyday life.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

It’s a fact of political life in the European Union that most Europeans eligible to vote at EU elections don’t vote. And yet, curiously, the EU’s leaders are not anxious about people’s lack of participation. No, they are seemingly more worried about those who are participating – in short, they’re worried about populism. So the big story of May’s EU elections was not that Europe-wide turnout fell to 42.54 per cent; rather, it was the alleged threat to democracy posed by the success of populist parties such as the Front National in France and UKIP in Britain.

Even in mature parliamentary democracies like Germany, Holland and the UK, the majority of the electorate didn’t bother to vote in May’s elections. But instead of asking why the elections failed to engage the interest of the majority of the European public, the EU oligarchy preferred to concentrate its energy on attacking and pathologising populist and Eurosceptic movements. When Germany’s vice chancellor, the Social Democrat leader Sigmar Gabriel, denounced Eurosceptic parties on both the left and right as ‘stupid’, he gave voice to a sentiment that is widespread among Europe’s political elites. They genuinely believe that these ‘ignorant’ parties are the real threat to democracy. In other words, it’s okay that millions abstain – after all, it means they’re not voting the wrong way. The EU establishment is clearly quite comfortable living with an electorate that is switched off and detached from the political process.

The exhaustion of European political life

The high level of abstentions in the European elections is symptomatic of the exhaustion of conventional political life in Europe. Since the late 1970s, and especially since the 1980s, the traditional parties of the left and right have experienced a profound crisis of identity. Many of the right-wing and centrist parties that dominated the postwar political landscape – such as the Italian Christian Democratic Party – have lost the capacity to motivate their dwindling support bases, losing votes and influence. The mass Communist parties of the left have all but disappeared, and social democracy has declined dramatically in influence. In response, mainstream party policymakers have embraced a self-consciously non-ideological, technocratic and centrist approach. In turn, the emergence of so-called Third Way technocratic governments has deepened the cultural chasm that separates the elite’s own worldview and interests from those of the electorate. Arguably the most significant manifestation of this development has been the disassociation of left-wing parties from the politics of class. And it’s this erosion of the historical relationship between the working class and parties of the left that has provided the ground on which populist movements are now flourishing.

Support for populist movements is not confined to the disenfranchised core of the old working class. For example, in the recent state vote in Saxony, the Eurosceptic Alternative for Germany Party won a surprise 9.7 per cent of the vote. Although a portion of its support came from former supporters of parties of the left, most of it came from people who had voted for the Christian Democratic Party and the liberal Free Democratic Party. What recent elections in the EU and elsewhere demonstrate is that populist movements represent an attempt to construct a political community that is otherwise absent in public life.

The issues at the heart of European populism are principally cultural. Yet, often, many attribute the rising influence of populist parties to the upheavals and dislocation caused by the economic crisis. No doubt the economic crisis in the Eurozone did foster a climate where protest movements – of both the left and the right – could flourish. However, it is important to note that the growth of radical populist parties preceded the Eurozone crisis. Moreover, many of the right-wing, identity-based parties have been most successful in the more prosperous regions of Western Europe, such as Lombardy, Denmark. Switzerland and Flanders.

An alien phenomenon

The recent electoral success of UKIP, the Front National and the Danish People’s Party, as well as the disturbing results of the more extreme Jobbik and Golden Dawn parties in Hungary and Greece, indicate that the conventions of postwar European politics face a new challenge. It is a challenge that the EU establishment and the media find difficult to fully comprehend. As Aurelien Mondon argues in his article ‘Nuancing the right-wing populist hype’, the role of these new parties is ‘widely misunderstood with potentially dramatic consequences’. Commentaries on the spectacular rise of right-wing populist parties throughout Europe often shift between incomprehension and moral condemnation. During the past two decades, and especially since the Eurozone crisis, such commentary often tends to pathologise populism, turning supporters of populist parties into patients who don’t quite know what they’re doing. It is said they are driven by resentment, or a desire to lash out against the political elites, or by their sense of helplessness before globalisation. They are portrayed as insecure individuals, suffering from a powerful and irrational fear – fear of others, fear of immigrants, fear for their national identity. And they are typically condemned as narrow-minded bigots or racists, embarrassing reminders of the prejudices of the bad old days.

The tendency to portray supporters of populist parties as simpletons is invariably combined with a view of the parties themselves as cynical exploiters of people’s grievances. At best, then, populist movements are seen in terms of a negative impulse, a backlash. The possibility that for many people voting for a right-wing populist party is a positive choice, and not just a protest, is rarely considered. Yet for many populist-party supporters, the decision to reject the established pro-EU mainstream parties is a positive move, an affirmation of a way of life.

Populist political culture is directly opposed to that of the technocratic elite. The moral and cultural contrast between the populist and technocratic outlook was strikingly illustrated during a recent interview with UKIP leader Nigel Farage on the issue of immigration. When Farage was confronted with the usual arguments about the economic benefits of immigration he chose to reject the premise of the interviewer’s question, arguing instead that politics was not just about economics. He showed that, for many people, the issue of immigration was not reducible to economic benefits; rather, it was the social consequences of immigration that concerned people. The argument that people cared about the future of their communities rather than economics caught his opponents unaware. Opinion makers and politicians are so wedded to technocratic arguments that they couldn’t understand what Farage was getting at. So although his point resonated with a large portion of the British public, his opponents and sections of the media dismissed it as proof of Farage’s economic illiteracy.

The tendency of the European media to represent populism as an alien pathology reflects their inability to take people with values and views opposed to their own seriously. European populism in all of its diverse forms – from the left-wing Greek SYRIZA movement to the right-wing Front National – is not merely hostile to the political institutions of the EU; it is also hostile to the cultural values of its elites. As the political theorist Margaret Canovan pointed out, unlike social movements, populism does not merely challenge the holder of power but also ‘elite values’ (1). Therefore, its hostility is also directed at ‘opinion formers and the media’. For their part, the media have a real problem in grasping the dynamics of populist politics. This problem is not simply the fault of the media’s shallow analyses. A significant section of the media is increasingly estranged from the life of working people and is intensely suspicious of those who do not share its cultural outlook.

This cultural conflict really is a clash between two very different worlds. The urbanised, university-educated and highly mobile political establishment has virtually no point of contact with those whose lives it scorns. And from the perspective of those who inhabit more traditional communities, the elite’s world looks alien and culturally distant. From the standpoint of a UKIP or Danish People’s Party voter ‘they’, the elites, really are ‘not like us’.

On occasion, cultural disputes that influence political debate in Europe can appear to be petty and bizarre. Recent controversies over the circumcision of Jewish and Muslim children or the wearing of the veil expose a profound mood of cultural insecurity. Take the issue of pork. Earlier this year, after reports that some nurseries in Copenhagen were no longer serving pork products, the Danish People’s Party decided to campaign against what it interpreted as a blow against the nation’s cultural identity. After its vociferous campaign provoked widespread indignation, the Social Democratic prime minister, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, was forced to acquiesce to the public mood and say that the eating of pork is integral to Danish identity. ‘We have to stick with the way we eat and what we do in Denmark’, she said, before adding, ‘there should be room for frikadeller [meatballs]’.

At first sight, the politicisation of meatballs appears absurd. But on closer inspection, it captures well the ‘enough is enough’ reaction of large swathes of the public. At least a significant minority of Danes felt that what they could previously take for granted is now regarded as negotiable by their political masters. That so many people reacted so strongly to the non-availability of pork in their children’s nurseries indicates that what’s at issue is their identity as Danes. They believe it is being challenged and redefined by forces beyond their control. Some commentators have simply dismissed those against the pork ban as xenophobic and anti-Muslim. No doubt, in some cases they are. However, this manifestation of cultural insecurity represents a demand for the affirmation of a way of life treated with disdain by the ruling elites.

Making sense of populism

In recent decades, ‘populist’ has become a term of abuse used to characterise radical protest. In the EU context, the word populist is now intimately associated with xenophobia, racism and an affinity with outdated and backward cultural norms and practices. ‘Populism in all its guises is anti-liberal, uninterested in nuanced solutions to complex problems, and always has the potential to be xenophobic’ – that is the verdict of one academic. Another, more charitable interpretation is that ‘populism might be described as the politics of offering easy answers while providing no real solutions’.

Yet, insofar as there is a common theme that characterises the disparate groups of people who voted for an anti-EU party like UKIP in Britain or for leftish groups like SYRIZA in Greece, it is the aspiration towards solidarity. Across Europe, significant segments of society feel psychically distant from their governments and institutions. They feel patronised by governments that believe less in representing the people than in using them to gain support for their pet projects. As a result, many people feel like strangers and outsiders in their own hometowns and countries. They believe that their habits, customs and traditions are being constantly ridiculed by an oligarchy that claims to have a monopoly on knowledge about what the public really needs. Little wonder, then, that many Europeans are drawn towards movements that promise to respect and affirm their ways of life.

Today’s political and cultural establishment rarely grasps this aspiration towards solidarity. Populist parties, by contrast, attempt to affirm this aspiration and claim to support the common people in a struggle against an increasingly alien elite. That is what populism is really about. Of course, populism comes in a variety of shapes and forms. Various motives, from chauvinistic revanchism to anti-immigrant racism, can inform populism. The trajectory of a populist movement is shaped by the competing cultural and political influences bearing down upon it. But contrary to the current association of populism with an impulse to stigmatise and exclude minorities, there are numerous examples of what the late American thinker Christopher Lasch called ‘democratic populism’. In his book The True and Only Heaven, Lasch described populism in America as a reaction to both the free market and the welfare state. He emphasised the significance populists attached to taking responsibility for their lives and circumstances.

In the US, it was precisely because populism was so often associated with egalitarian democracy that sections of the American left used to support it. Indeed, it is worth remembering that, historically, many populist movements, such as the English Chartists, were associated with the politics of the left. As the American historian Michael Kazin observed, the language of populism was an inspiration to left-wing movements during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was only in the 1940s that American populist discourse started to migrate from the left to the right. In principle, there is no reason why the populist imagination should be monopolised by a single political voice.

Certainly in contemporary Europe, populism has become a political style embraced by myriad, heterogeneous ideological movements. At a time when millions of Europeans feel ignored and patronised by a political elite that treats them with contempt, their embrace of populism is not at all surprising. In fact, this reaction against an arrogant elite that treats the public as its moral inferiors is, on balance, a healthy development. Populism presently serves as the principal medium for responding to the EU oligarchy’s anti-democratic style of technocratic governance.

However, populism on its own is not enough. To address the EU’s democratic deficit, what is required today is the crystallisation of the populist impulse into a political movement that might infuse the aspiration towards solidarity with the ideals of popular sovereignty, consent and an uncompromising commitment to liberty. Now that could really represent the making of a movement to shake up public life and add meaning to politics.

Frank Furedi’s First World War: Still No End in Sight is published by Bloomsbury. (Order this book from Amazon (UK).) He will be speaking at various sessions at the Battle of Ideas festival, held at the Barbican in London on 18-19 October, including Is demography destiny? and After Gaza: the return of anti-Semitism? Get tickets here.

Picture by: PA Images.

Footnotes:

(1) ‘Trust the people! Populism and the two faces of democracy’, by Margaret Canovan, Political studies 47.1 (1999), pp2-16

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.