The British Museum has lost its marbles

Why loaning the Elgin Marbles to Russia is a mistake.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

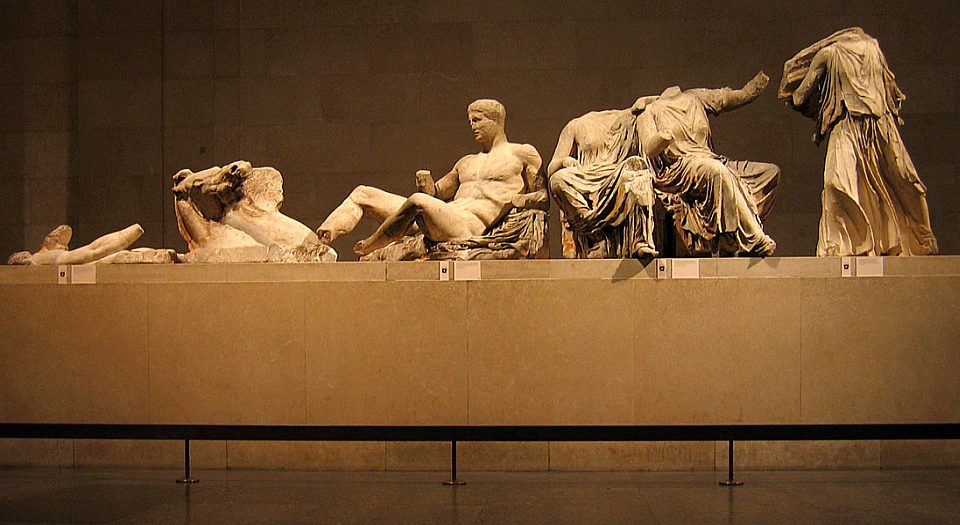

In a provocative act, the director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, has sent one of the Elgin Marbles to Russia, on a temporary loan. It followed a request from the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, which wanted to exhibit the marble as part of its 250th anniversary celebrations. The sculpture is probably of Ilissos, a Greek river god. It is a marble figure of an athletic young man, drawing himself up on to a bank. He is naked, bar a drape falling over his left side, which is so artfully carved that the cloth appears to turn into water.

This is the first time any of the marbles have left Britain since they arrived here over 200 years ago. The loan has angered those who think that if the marbles are to go anywhere, they should go to Greece, where they once formed an integral part of the Parthenon (a 2,500-year-old temple dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena). But these critics are wrong. The Elgin Marbles should remain in the British Museum. The present situation – where half the remaining sculptures are in Athens and the rest are in London – is a good one. It means the marbles can be seen and understood both in Athens, in the Acropolis Museum close to where they were created, and in London, where they are placed within an encyclopaedic collection of artefacts from multiple human civilisations: this aids an understanding of the influence of the sculptures and the ideal of ancient Athens on many other cultures around the world.

Some argue that the original circumstances of the marbles’ acquisition were questionable and therefore they should be returned to Athens. But Lord Elgin neither looted nor stole them. The Parthenon in the early nineteenth century was a ruin. Locals were using blocks from it for their own purposes, and travellers and antiquarians were taking as much as they could carry home with them. Elgin took more than most: he shipped back around 200 tonnes of sculpture, but he also had a letter of agreement – a firman – from the ruling Ottomans allowing him to do so. Elgin’s agents may have taken more than they were meant to, but the acquisition was all above board.

But the loan to Russia is troubling. For a start, loans are not automatically a good thing. Yes, more people get to see the art, but this comes at a cost. The British Museum boasts that it is the most generous lending collection in the world: over 5,000 objects from its collection travelled to 335 venues across the world in 2013-14. While many benefit from these loans, there are risks. The dangers are obvious: transporting precious, unique and fragile works around the world can mean damaging them. Last year, a committee in the Scottish parliament was considering whether to allow Glasgow’s Burrell Collection to tour some of its treasures, against the will of the donor. Nicholas Penny, director of the National Gallery in London, sent a letter to the committee, which was later accidentally posted on the Scottish parliament’s website, warning that ‘moving works of art has led to several major accidents, incidents and damage to works, of which many have not come to public attention’.

We have to ask: why loan these artefacts? Is it worth the risk? The reason stated in this case is that Ilissos has been sent in the services of soft power. As MacGregor put it: ‘The politics of both museums has been that, the more chilly the politics between governments the more important the relationship between museums.’ Similarly, a recent lead article in The Times claimed the loan was ‘an invitation to all who visit the new exhibition to embrace the values that bind Russia to Europe and shun those that rationalise thuggery’. Thus, the loan has been presented as an act of cultural diplomacy. It is hoped the loan will warm up the frosty relations between Russia and the West. In other words, the loan is not driven by scholarship or access questions, but by political diplomacy.

Of course, you’re never far away from politics and power in museum studies. Museums, and the artefacts they hold, have always been political; they always reinforce power, or at least that’s how the common critique in academia goes. It is an approach I often criticise, but it is not entirely groundless. What these studies often fail to do, however, is explicate the difference between how the museum of the past was used – with what political purpose – and how museums are used today. As a result, the theorising is often ahistorical and circular and misses what is distinct between the past and present.

The Elgin Marbles have sparked controversy ever since they arrived in Britain. When they first arrived it sparked a stormy row. The difference then was that the debate was less over their ownership and the circumstances of their acquisition, and more over the marbles’ value and meaning.

The marbles were acquired at a time in which there was a shift in taste – a move away from Neoclassicism to Romanticism – and they became the focus for fiery arguments about aesthetics. Many erudite men were unconvinced that the marbles were all that special – the sculptures lacked the smooth and finished quality of the Roman works which were popular at the time. Few people would get to see Ancient Greek artefacts and, when they finally got the chance, some thought the bruised and broken sculptures were inferior. Royal Academician Ozias Humphry admitted the marbles had ‘something great and of a high style’ but described the lot as ‘a mass of ruins’. The focus of debate then was the quality and value of the sculptures.

In time, the Elgin Marbles came to be loved – practically worshiped – and were purchased for the nation. The reason for this purchase is interesting. With these sculptures, the cultural and moral achievements of Ancient Greece, intertwined as they were, could be born again in England. English artists, and the nation as a whole, could well be morally inspired by these works, or so the thinking went. Something similar happened in Greece. After the Greek Wars of Independence, the Ottomans were defeated. In 1832, Greece was recognised as an independent nation with an appointed Bavarian King – Prince Otto, son of King Ludwig of Bavaria. The new political elite understood that the values and artefacts of Ancient Athens could be put to some political use, too – they could be used to reconstruct a sense of a long, and credible, history for the nation. The Greeks began to glorify Ancient Athens and its Antiquity. The interests of the Bavarian monarchy chimed with Greek intellectuals, and indeed the English, who expressed an idealism about the glories of Ancient Greece.

So, yes, the marbles have always been put to political use, but this loan to Russia is different. This is about soft power, improving relations between countries, rather than inspiring people with the artworks and the values of the ancient world. The loan is an attempt to show the relevance of museums to modern society. If they can prove they are essential to international relations, they might survive.

These strategies threaten the future of the museum. Pursuing social outcomes that museums can’t possibly achieve will come at the cost of their core role: research and dissemination of knowledge. The decision to loan the marbles to Russia shows that museum heads today have things completely the wrong way around: artefacts should not be put to work for the museum; the museum should be put to work to understand the artefacts.

Tiffany Jenkins is a cultural sociologist and author. She is currently writing her upcoming book Keeping Their Marbles.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.