That Sugar Film: demonising the sweet stuff

A new Aussie documentary should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Back in 2004, Morgan Spurlock, a largely unknown writer and performer, achieved global fame with his movie Super Size Me. The premise was simple. Spurlock would eat nothing but McDonald’s for 30 days and see what effect it had on his health. To add an extra twist, Spurlock would take the ‘supersize’ meal deal whenever he was offered it, which seemed to be quite often. As a result, he consumed over 5,000 calories per day (roughly twice what an average man would require), gained weight, and apparently, within just a few weeks, suffered life-threatening changes to his body.

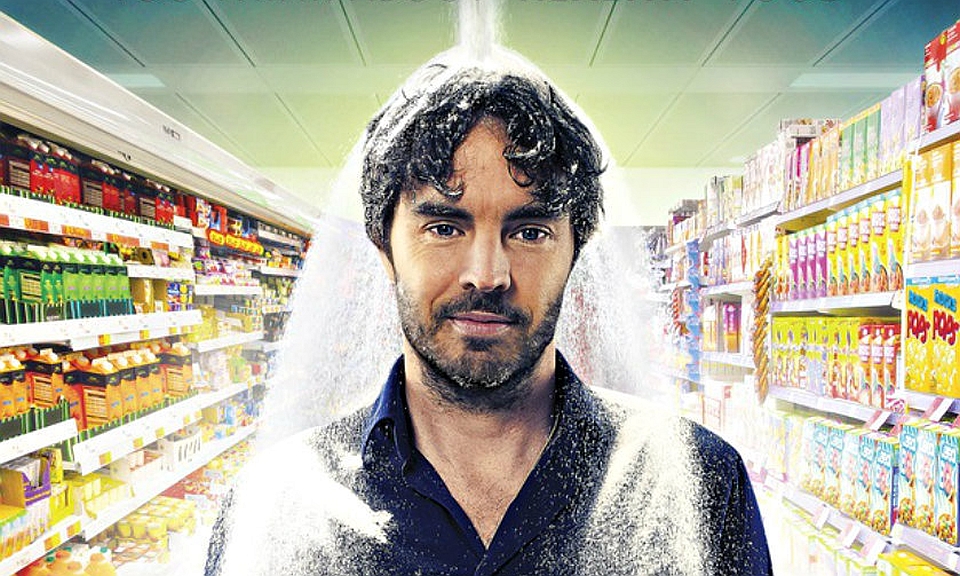

Ten years later, another largely unheralded performer, Damon Gameau, has recycled the idea in a new film, Sugar Size Me. Actually, it’s not called that, but clearly unable to get past the behemoth that was Spurlock’s achievement, he ended up calling his effort That Sugar Film. But the dubious central point is the same: eat a bad diet – this time for 60 days – and watch the ill-effects emerge.

A few years ago, after meeting his girlfriend, who we learn is also the soon-to-be mother of his child, Gameau gave up eating all refined sugars. So at the start of the movie, he’s a wiry specimen of good health. But he’s confused. He’s been reading all this stuff online about sugar and doesn’t know what to make of it. At one point, he appears to be reading my spiked article The sweet truth: 10 myths about sugar. But the rest of the film suggests he didn’t bother actually to read it. Still, thanks for the publicity, Damon!

So, to find out for himself just how bad sugar is, he decides to eat a diet of apparently healthy food that is, in fact, full of sugar. Now to be fair to Gameau, he doesn’t just neck a big bottle of full-sugar Coke every day to get his allocation of the sweet stuff. No, he eats processed foods and even drinks fruit juices that are promoted as being good for you. According to his expert adviser, David Gillespie, he needs to consume 40 teaspoons of sugar every day to match the intake of the average Aussie. Gillespie is not a doctor or expert researcher – he’s a corporate lawyer and the author of Sweet Poison: Why Sugar Makes Us Fat. Not necessarily the most authoritative source of information, but Gameau attempts to make him seem cool by giving him the nickname ‘The Crusader’. (There’s a lot of this grating ‘fun’ in That Sugar Film – as the closing song illustrates.)

Forty teaspoons of sugar a day? That seems an astonishing amount, and it probably is on the high side. According to the Australian Health Survey (AHS), published in 2014, men consumed about 2,300 calories per day. Of that, 20 per cent, or 460 calories, came from sugars. That’s about 29 teaspoons, including all sugars in the Aussie diet. Before we get too excited, the survey suggests 16 per cent of that sugar came from fruit, about nine per cent from milk and seven per cent from fruit-and-vegetable juices and drinks. This isn’t simply a case of food manufacturers stuffing foods with sugar – a lot of dietary sugar is in ‘natural’ foods. By comparison, just under 10 per cent came from soft drinks.

In fact, it’s not really clear whether Gameau thinks this is an ‘average’ amount of sugar or a ‘high-sugar diet’. But just to let us know that it’s bad, whatever the case, the people he turns to for health checks and advice tell him he shouldn’t ‘do this crazy thing’, that it’s ‘insane’. If this was the build-up to some David Blaine-style stunt where he gets manacled and then dropped into a shark tank, that kind of language would be appropriate. But as the prelude to eating sugar? It’s the language, not the diet, that’s insane.

At this point we have a little vignette, featuring actor Hugh Jackman, about the history of sugar, which claims that Queen Elizabeth I had black teeth because of her love for what was then a luxury product (probably true, though the absence of decent dentistry can’t have helped), and that even at the start of the twentieth century, sugar was still an unusual treat. That might be the case for Australia, but it certainly wasn’t in the UK, where sugar was an essential part of the poor diets of the working class – indeed, sugar consumption may even have been higher in 1900, when dinner might well have meant bread and sugary jam, than it is today.

But why should sugar concern us more than other foods? As Stephen Fry (feel free to roll your eyes) explains in the film, table sugar – sucrose – is actually two simpler sugars: glucose and fructose. Glucose is present in any starchy food and Aussies get more calories from starch – as found in bread, rice, pasta and so on – than they do from sugars. But fructose is, Fry assures us, a sugar that we have little capacity to metabolise in large quantities and so it gets converted to fat in our livers and blood. Meanwhile, all that glucose also makes us gain weight because it promotes the production of insulin, which encourages our bodies to store fat.

Now it is certainly possible that too much carbohydrate in our diets causes some of us to pile on the pounds over time. But whether sugar is particularly bad for us, more so than other forms of carbohydrate (or any other source of calories for that matter), is much more controversial. For example, John Sievenpiper, a researcher from Toronto, argues that the claims about sugar are based on feeding huge quantities of fructose to animals that metabolise fructose very differently to humans. But, we are assured by Gameau, we can safely ignore him because he is (sort of) in the pay of Big Soda. This kind of ad hominem attack is typical of sugar campaigners, who have attempted to discredit nutrition researchers in the UK in much the same way. There is no note of doubt in That Sugar Film, just a one-sided version of events.

The inevitable result of Gameau’s diet of fruit juice, sugary yogurt and convenience food is that – shock, horror! – he puts on a few pounds. We are also told that he starts to develop fatty liver disease, to the apparent astonishment of his doctor (and, frankly, me). He also claims to experience psychological effects from consuming sugar, becoming manically hyperactive one minute then lethargic the next. People are ‘up and down’ the whole day, he says, but we don’t notice because that’s what we’re used to. Our minds are ‘fuzzy’ all the time. He can’t wait to get back to his wholesome diet when it’s all over.

At this point, the film tips over into full space-cadet mode. We can’t imagine life without sugar. It’s central to celebrations in Western societies because we associate it with love. In fact, sugar actually evokes the feeling of love because our brains ‘respond to the chemical effect the same way we respond to love’. One talking head, David Wolfe (who can also be seen in the UK flogging overpriced food blenders on early morning infomercials), even claims that ‘sugar causes materialism’. The ‘sugar-drug’ culture created the materialistic culture. Sugar supplies energy ‘straight to the brain’, we are told, leading us to become unwilling to defer any gratification.

Thankfully, it all ends happily ever after. Gameau switches back to his sugar-free diet and reverts to his healthy self, and the baby is born. The message is clear: don’t mess up your health with that mind-fucking shit.

Gameau is perfectly entitled to his point of view, no matter how wacky it is. What’s really worrying is that he is being taken seriously in the media (see the BBC News interview as an example). Sugar is not a health food. No one would argue that these days. Consuming large quantities of it, especially if it leads to an excess of calories, may well increase your waistline. But to demonise one specific kind of food, and turn it into a conspiracy theory about big business wrecking our health, is positively medieval.

Rob Lyons is campaigns manager at Action on Consumer Choice and author of Panic on a Plate: How Society Developed an Eating Disorder. Visit his website here.

Watch the trailer for That Sugar Film:

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.