Operation Midland: the hysteria of ‘believing the victim’

The ‘VIP paedophile’ panic poses a serious threat to justice.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

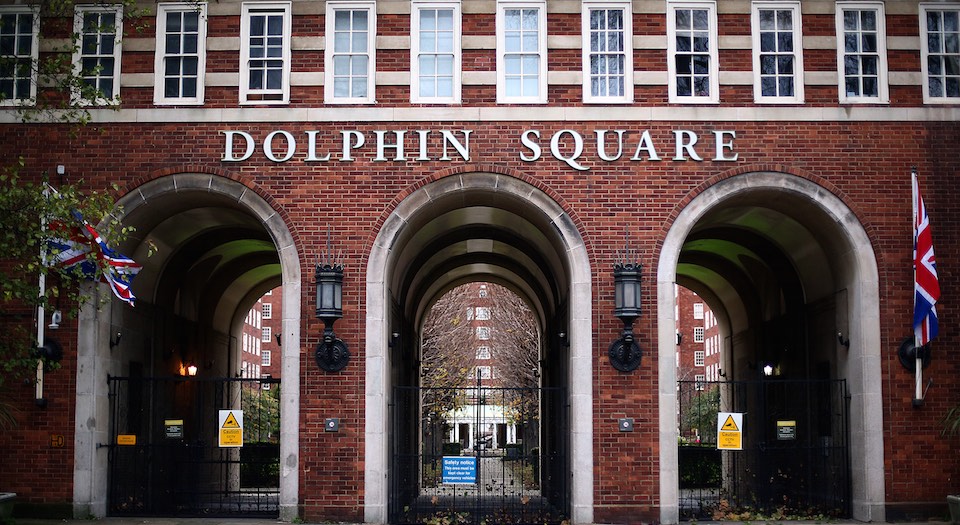

The saga around historical-abuse investigations has reached a new low. The police have publicly criticised BBC TV’s Panorama after last week’s episode revealed serious flaws in Operation Midland, a police investigation into an alleged high-profile paedophile ring in the 1970s and 80s. Panorama raised concerns that the police had launched the investigation on the basis of weak evidence. A man who made some of the allegations told reporters that he felt pressured by campaigners to provide police with names of ‘VIP paedophiles’, including that of former home secretary Leon Brittan. The Metropolitan Police said it had ‘serious concerns’ that Panorama would deter victims from coming forward.

It is hardly surprising that serious issues around the police’s approach to historical-abuse allegations are now coming to public attention. At spiked, we have noted that, since the beginning of Operation Yewtree, the post-Savile investigation into historic-abuse claims, police have abandoned the normal rules of objectivity and impartiality. The desperate desire among the police to ‘believe’ complainants seems to have overridden their duty to investigate cases properly. Now, complainants are routinely referred to as ‘victims’ and ‘survivors’ by both the police and the media, long before their claims have been properly scrutinised.

But the problem is not just within the police. Today, being an abuse survivor has become a cultural identity all of its own. ‘Survivors’, a term applied even to people who have made unproven historical allegations against people who will never be able to defend themselves, hold great sway over major public institutions. Take, for example, the conduct of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, launched by the government in 2014. Two prospective chairs were appointed to lead the inquiry but were later ditched because of concerns raised by survivor networks. Prosecutors routinely address ‘survivors’ as though they are a homogeneous political-interest group. These ‘survivor groups’ are often made up of people who have never been to court or had their evidence tested.

Of course, genuine victims of sexual crimes show great courage when bringing their complaints to the attention of the authorities, and they should be given all the support they need in order to ensure that their complaints are taken seriously. The problem today is that we seem to venerate sexual-abuse complainants, as though the act of making an allegation is, in and of itself, a societal good. We can hardly be surprised that extremely harmful complaints can turn out to be false when the media and the prosecuting authorities celebrate making allegations against vulnerable people as a marker of personal courage.

This is why we should welcome greater scrutiny of these allegations, both in the name of fairness and objectivity and in the name of achieving justice for all genuine victims of abuse and sexual violence. While we should encourage victims to come forward with their complaints, we should also accept that sometimes people are capable of coping with the bad things that happen in their past without requiring the intervention of the authorities. We should also discourage people from reflecting on negative experiences in their past through the prism of sexual violence. Of course, it is never good if an abuser gets away with it, but neither is it good if every old man who has ever behaved in an inappropriate way with a young person is hauled before the courts. The justice system is there to deal with those who genuinely, in the eyes of society, deserve punishment. If we abandon our sense of judgement about how this should be applied, then judicial punishment can easily become a vehicle for harmful witch-hunts.

That is why we should welcome any scrutiny of sexual-abuse allegations, whether it be by the police or – where they fail to do their job properly – by investigative journalists. Last week’s Panorama seemed to mark a break in a long-standing relationship between the police and the media with regard to sexual-abuse investigations. Both the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the police have used the media to make public apologies about their failure to prosecute sexual-abuse cases in the past. Indeed, it was a TV programme that first gave birth to Operation Yewtree, when the ITV documentary Exposure: The Other Side of Jimmy Savile revealed several allegations against the late TV presenter. The police were only too happy to court the services of the media when, in the aftermath of the Savile allegations, they sought to use TV and radio programmes to call for more complainants to come forward.

Now that journalists have raised doubts about the veracity of certain sexual-abuse allegations, the police are criticising them for failing to toe the official line. It is absurd and counterproductive that such serious criminal investigations have, for the past few years, been played out in public between the police and the news media in an unhealthy scrap over the truth.

This relationship between the media and the police has been bad for justice. From the start of Operation Yewtree, the use of the media by the police to trawl for more and more victims, to make constant public proclamations that police officers will ‘believe’ complainants, all in the hope of presenting the media with an image of a more caring and compassionate police force, has created an atmosphere in which the impartial and objective investigation of evidence has become impossible. It is time to end this unhealthy relationship and reintroduce robust scepticism into the investigation of historical sexual abuse.

Luke Gittos is law editor at spiked, a solicitor practicing criminal law and convenor of the London Legal Salon. He is the author of Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. Why Rape Culture is a Dangerous Myth: From Steubenville to Ched Evans. (Buy this book from Amazon(UK).)

Luke will be speaking at the sessions ‘Blurred lines: what is consent?’ and ‘Rape culture: menace or myth?’ at the Battle of Ideas festival in London on 17-18 October. Get your tickets here.

Picture by: Getty Images / Carl Court / Staff

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.