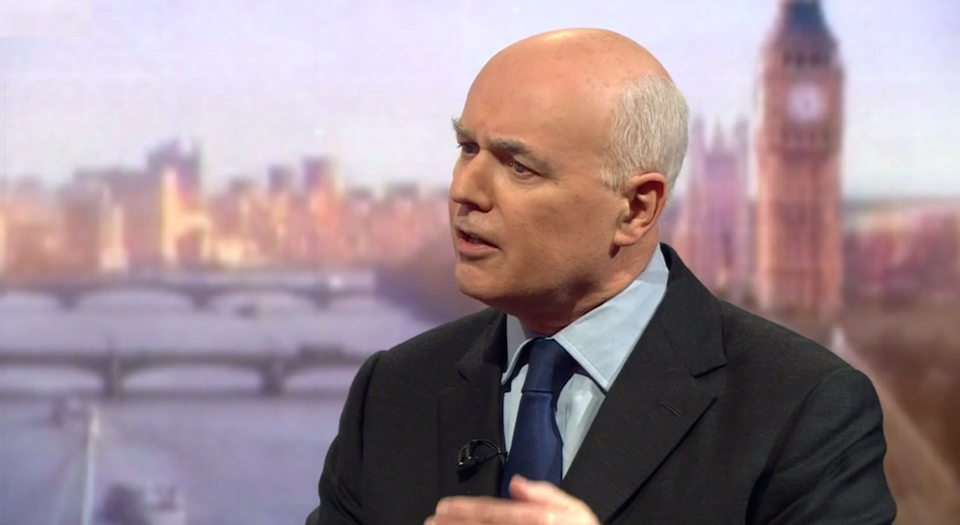

IDS and the ‘narcissism of small differences’

There is both more and less to the Tory civil war than the headlines suggest.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Why is the UK’s ruling Conservative Party publicly tearing itself apart after the resignation of welfare secretary Iain Duncan Smith? Is it about disability benefit cuts, the EU, the Tory leadership, or what? It seems there might be both more and less going on here than meets the eye.

The departing IDS insists that the row really is all about welfare reform, specifically the ‘indefensible’ changes to disability benefits announced in chancellor George Osborne’s Budget last week. There are obvious tensions over the public-spending deficit and welfare policy, which have now led to the shelving of those proposed cuts to disability benefits. Yet some might find the idea of the Tories suddenly fighting a civil war over the welfare cuts to which they have long been committed an unconvincing explanation. Especially as IDS himself happily led the government’s crusade to cut welfare payments as secretary of state for work and pensions for almost six years.

Critics, meanwhile, claim that the row about disability benefits is largely a smokescreen for the real conflict among the Tories, which is over Europe. They point out that IDS and other new Tory critics of government cuts are all prominent supporters of the Brexit campaign for a vote to leave the EU in the June referendum – that is, in the opposite camp to Osborne and prime minister David Cameron.

Of course, Europe has long been a divisive issue for the Tories. But that alone can hardly explain why a veteran Eurosceptic such as IDS, having said nothing against the EU for the past decade, should suddenly use disability benefits as the pretext to resign from the government – especially when he had been granted leave by Cameron to campaign for Brexit from the frontbench. Nor can the age-old Tory argument over the EU really explain why someone such as London mayor Boris Johnson, long seen as a cosmopolitan Europhile, should have become a Brexit convert and critic of the government apparently overnight.

Others say that all of these issues are merely being used as grist to the mill of the coming Tory leadership struggle. Cameron, they point out, has let it be known that he does not intend to serve a third term as prime minister. Chancellor Osborne is widely seen as his chosen successor. Conservative critics and rivals are therefore said to be taking up any stick, from welfare policy to Europe, with which to beat the prime minister and particularly to do down Osborne, his less popular heir apparent.

As with the welfare and EU explanations, leadership tensions are clearly a factor in the current Tory meltdown. Boris’s ambitions to succeed Cameron certainly help to explain his repositioning on the EU referendum. But it would normally be unimaginable to see such a challenge to a prime minister only months after he had won an unexpected overall majority at a General Election. Cameron’s authority in the Conservative Party (if, perhaps, not in the country) should be at its peak. Yet suddenly there is shrill talk in the Westminster corridors of a swift leadership election after the June EU poll, and even, in the hysterical-sounding words of one leading Tory MP to a BBC correspondent, of a ‘genocide of the Cameroons and Osbornites’.

So, what’s brought all these issues to a head now? The crisis in the Conservative Party appears to be over issues that are both bigger and smaller than the headline debates suggest.

Bigger, because it is not just about this spending cut or that referendum. It is more fundamentally about the implosion of the centre of the Conservative Party – and of UK mainstream politics more widely. And, at the same time, smaller, because, in the absence of bigger unifying political principles to hold the party together, petty issues of personalities, grudges and gripes can become all-consuming – even when focused on such a non-personality as IDS.

The Conservatives, the party of British capitalism and the Empire, have fought, fallen apart and regrouped before. But battles have tended to be over historic issues close to their heart – the struggle over Irish independence, say, or rearmament and the appeasement of Hitler – rather than a proposed £30 cut in disability benefits. Indeed, such an economic conflict – involving, in the words of IDS, ‘people who don’t vote for us’ – would traditionally have united rather than divided Tory forces.

Things are different now because the old Conservative Party no longer exists. Yes, it still appears on ballot papers and in parliament as an electoral machine. But it no longer exists as a coherent political party with unifying principles and goals that can overcome minor differences. The political centre of traditional Toryism has imploded, the gap filled only by PR men such as Cameron and management-speak policy wonks such as Osborne.

The long-running rows over Europe in Conservative ranks are one product of their loss of a political mission and identity. For them, the European issue is now about what role Britain – and the Tory Party – should aspire to in a post-imperial world where they would struggle to replicate Margaret Thatcher’s Falklands triumph, never mind Winston Churchill’s victory in the Second World War.

In a sense, the political emptying-out of the Tory Party mirrors what happened to the Labour Party, which allowed Tony Blair and the New Labour clique to take power. One consequence of that was to usher in an era of back-stabbing court politics, where personal factions around Blair and Gordon Brown within the government competed to assassinate their internal enemies.

What we are witnessing now is partly the Tory equivalent of those sub-Shakespearean struggles between courtly factions. In the absence of great political principles to unite or divide them, even over Europe, petty issues of personal ambition and envy can come to the fore.

It looks less and less like the political civil war reported in the media, and increasingly like a modern political example of what Sigmund Freud referred to as ‘the narcissism of small differences’.

Hence Boris can effectively switch sides over the EU referendum, supposedly ‘the biggest issue for a generation’, because it seems to suit his own short-term game of one-upmanship. And the Conservative government, just months after winning the General Election, can be torn apart by the personal grievance that IDS evidently feels at being snubbed from above, and the schoolyard animosity between him and Osborne.

It is truly pathetic that the party that has ruled the UK for much of the past century or more should effectively be brought to its knees by the narcissism of small differences. It is also a powerful advert for the need to raise the level of political debate around the big issues that matter in the EU referendum and beyond.

Mick Hume is spiked’s editor-at-large. His book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by Harper Collins. (Order this book from Amazon(USA) and Amazon(UK).)

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.