From Brexit to Grenfell

Why the left prefers the poor when they’re tragic and vulnerable.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Over the past year, between June 2016 and June 2017, there have been two major disturbances in Britain. The first, the Brexit revolt, was politically disturbing. It disturbed the establishment. It rattled the political class as much as it thrilled those of us who oppose the EU because we favour democracy over technocracy. The second, the Grenfell Tower inferno, was horrifically disturbing. It disturbed the peace of the nation. It disturbed our civilisation. It will leave an indelible mark in British history. As will Brexit, of course. Both these June disturbances, coming a year apart, will define Britain for a long time to come.

But what is extraordinary is this: many on the left and in so-called liberal circles see the second disturbance, the horrific one, the one no one designed, as more political than the first. Indeed, where they devoted a huge amount of intellectual energy to depoliticising the Brexit disturbance, branding it a ‘howl of rage’ motored less by political conviction than by ‘the lowest human impulses’, they have dedicated similar zeal to politicising Grenfell. This inferno represents a ‘sea change’ in our political life, ‘symbolising the end of an era in British politics’, say the same observers who raged against the idea that Brexit was a political shift we should respect. The fire speaks to them more clearly than Brexit does. And this reveals more about modern liberals than they would like us to know.

One of the words most commonly used in relation to the Grenfell inferno is ‘voiceless’. This calamity proves, observers say, that the poor of Britain are voiceless. No one takes their concerns seriously. It shows that ‘the weak’ – the Dickensian phrase used by one magazine – are too often ‘silenced, ignored or discounted’. It shows that too many people in this nation are ‘vulnerable and voiceless’, says Labour MP David Lammy. The poor are ‘trapped and voiceless’, says a writer for the Financial Times. But of course, the poor, for all their troubles and lack of everyday clout, do have a voice. And it’s a voice equal in strength to the voice of the richest people in the nation. It’s called the vote. And last June, during the first of the June disturbances, when vast numbers of the poor used that voice to say ‘We want to leave the EU’, they were demonised, ridiculed, referred to as ‘low-information’. By the same people now crying over their voicelessness.

This is most clear in the increasingly ridiculous figure of David Lammy. Lammy has pushed himself to the forefront of politicising Grenfell. He wants to be a voice for the voiceless. We must be a society where ‘we care for the poorest and the vulnerable’, he says. This is the same David Lammy who following the first June disturbance, following Brexit, devoted himself to overthrowing the voice of the voiceless. He put himself at the cutting edge of the elitist revolt against the demos. ‘We can stop this madness’, he said. He called on his fellow MPs to ‘bring this nightmare to an end’. We cannot ‘usher in rule by plebiscite which unleashes the “wisdom” of resentment and prejudice’, he said, with Victorian-level snobbery.

And now he expects us to believe him when he says he wants to hear from the voiceless? Clearly he really does think we’re stupid. Behind that ‘nightmare’ of Brexit that he wanted to destroy there were millions of poor and working-class voices. Indeed, as a major study at the end of last year found, the largest pro-EU vote was among the richest in Britain, in social class AB, whereas in the lower social classes, including D and E, the lowest of all, there were clear majorities favouring Brexit. The report concluded that, ‘At every level of earning there is a direct correlation between household income and your likelihood to vote for leaving the EU’. Shorter version: in very significant numbers, the poor voted Leave. And yet Lammy mocked them and their ‘wisdom’ (his quote marks), claiming they were driven by ‘resentment and prejudice’.

He wasn’t alone, of course. Across the so-called liberal establishment, last June’s political disturbance gave rise to a long, unforgiving sneer at the masses. The people who voted for this were ‘low-information’. They’re ‘ignoramuses’, said Richard Dawkins. They were thinking with their ‘lizard brains’, said a writer for the New Statesman, a mag that now says ‘we must politicise the tragedy of Grenfell Tower’. To see Brexit through would be to give in to ‘crowd acclamation’, said AC Grayling, and we all know how stupid and foul the crowd is, especially a crowd made up of people who didn’t go to university, people from social classes D and E. Shudder.

The chattering classes’ immediate instinct was to deprive Brexit of its conscious, political core. This wasn’t a thought-through political demand, they insisted. It was a howl, a crowd screech, an act of ignorance, the work of people hoodwinked by demagogues. Or, among the more generous, but equally paternalistic sections of the media class, it was ‘the cry of the left behind’. This cry would need to be defused, they said, or ‘softened’, to use the preferred Orwellian parlance. For the same people who have spent a year seeking to shush the voice of a vast swathe of the population, including significant numbers of poor people, now to weep over the voicelessness of the poor requires industrial levels of brass neck. It is incredible, actually. The clear, conscious demand by many poor people and others for a sea change in British politics was ridiculed, while the horrendous enveloping of a building in flames is welcomed as a sea change in British politics.

This shift between Brexit and Grenfell, from feeling horrified by the voice of the masses to crying over the voicelessness of the poor, tells us an important story about what passes for left-wing and liberal politics today. It reveals how far being left has become bound up with feeling a 19th-century-style pity for ‘the vulnerable’, that dehumanising phrase so often applied to less well-off people. The assumption is always that these people cannot govern their own lives; they lack the moral and intellectual resources required for a good, fulfilling life, and so they require the intervention of the caring state and caring liberals to look after them. And speak for them. This is why poor people’s use of their voice last June so horrified the media class, while the image of Grenfell, of poor people caught up in a horror beyond their control, voiceless in that moment, has gripped them so. It ‘perfectly captures’ politics today, says Polly Toynbee. Perfectly. Because it flatters her moral sense that she, and her left, must lead and assist the poor.

These people have no interest in hearing the voice of the poor. They want to speak through the poor. ‘Give a voice to the voiceless’, says one headline on the Grenfell inferno. This is political ventriloquism, of the most ghoulish variety, where the dead poor are made into political placards to push the messages of a middle-class left. Between Brexit and Grenfell, between these two disturbances, we have had an alarming insight into the mind of the modern left: it prefers the poor when they are screaming for their lives rather than when they’re calmly demanding political change.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

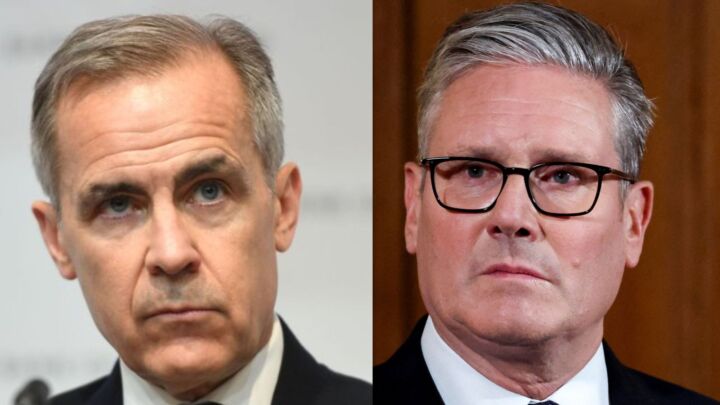

Picture by: Getty

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.