Elena Ferrante and the 21st-century crisis of identity

What the Ferrante story tells us about art and humanity.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

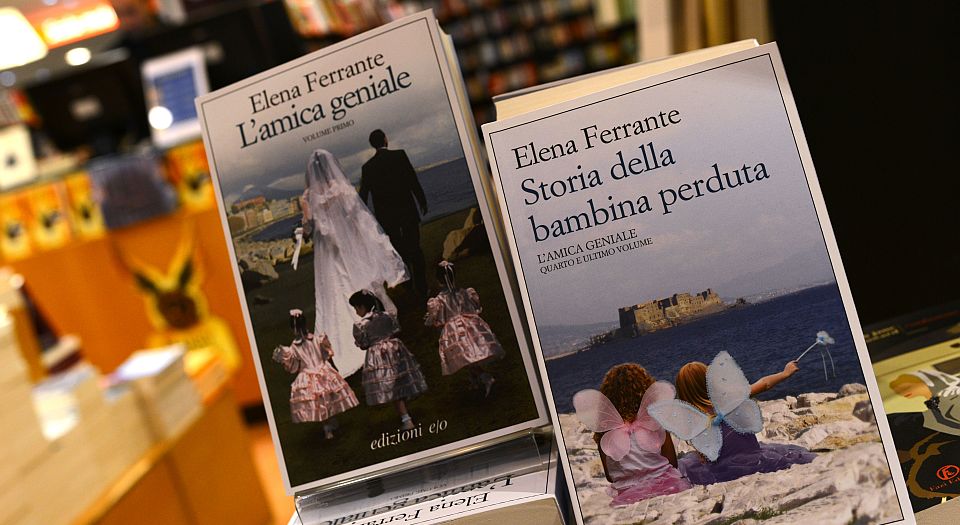

This week the literary set had a hissy fit over the unveiling of Elena Ferrante’s identity. Ferrante, the wildly popular Italian writer, best known for her quartet of Neapolitan novels, is Anita Raja, a translator who lives in Rome. So claims Italian journalist Claudio Gatti, in a pretty thorough, stacked-up piece for the New York Review of Books that seems finally to have solved the riddle of the world’s most famous literary pseudonym. Yet judging from the response to Gatti — a nasty voyeur, we’re told; a charlatan seeking his ‘15 minutes of fame’ — you’d be forgiven for thinking he’d taken up-skirt shots of Ferrante/Raja or published her home address, rather than simply investigating her backstory. His hackery is the ‘literary equivalent [of] rifling through someone’s bins’, says one columnist. A snooty New Yorker piece mocks Gatti’s writing style and brands him ‘smug’. He’s a sad, failed male writer ridiculing a successful female one, says one observer, because every criticism of a woman is misogyny, right?

This literary-set closing of ranks behind one of its own might be touching, but it’s also wrong. I think privacy is incredibly important, and far too casually given up these days. (Which makes it a shame that not one of the British commentators crying over the exposure of Ferrante saw fit to criticise home secretary Amber Rudd’s promise to get ‘behind closed doors’ and make home life in Britain more ‘transparent’, which she made on the same day Gatti’s piece was published. Perhaps only successful literary women deserve privacy, not those ‘bad mums’ or ‘chaotic families’ the UK government is keen to spy on?) However, the unveiling of Ferrante is not a simple privacy issue. It’s also about truth. The fact is Raja/Ferrante has been dishonest about her background, and this raises questions about literature, identity and the 21st-century obsession with cultivating authenticity (a contradiction in terms, of course) that are of keen public interest. Her identity, or rather her playing with identity, is, I’m afraid, a public-interest matter.

Anonymity can be a good thing, but not always. Sometimes it’s used for positive ends, such as when dissenters in tyrannical regimes tweet or agitate under a shroud of secrecy, and sometimes it’s used for bad, like when an internet troll masks himself so he can hurl invective at people he doesn’t like. Ferrante/Raja, a brilliant writer, is far from a troll; but her anonymity also doesn’t fall neatly into the positive category. It involved, it seems, deception. The presumption long made about Ferrante, because her Neapolitan books are so evocative, is that she herself is a native Neapolitan. And Ferrante frequently fuelled this notion. In a rare interview a few years back, she told the Paris Review she ‘grew up’ in the ‘periphery of Naples’. She has also said her mother was a seamstress, and that in rough Naples she witnessed ‘crude family acts of violence’. Her newly published memoir-of-sorts, featuring letters and interviews, tellingly titled Frantumaglia (‘Falling apart’), tells of how she uses her Neapolitan childhood ‘as a storehouse for memories, impressions’. She presents herself as someone who became a woman in harsh, colourful Naples. We now know, if Gatti is correct, that this isn’t true. And that is unquestionably interesting, and important.

If Gatti is right in his investigation, and it seems pretty certain he is, then Ferrante, Raja, is really the daughter of a schoolteacher from Germany and she grew up in Rome, not Naples. She was born in Naples but left at the age of three, so cannot have any meaningful childhood memories of it. This is significant, both at the basic level that Gatti has corrected seeming falsehoods — the myth that Ferrante grew up in Naples the poor daughter of a seamstress — and at the bigger level of raising questions about identity and literature in the modern period. If a good journalist is one who investigates public claims he thinks are misleading, then Gatti must be congratulated for good journalism. And if we’re serious about having an intelligent, rigorous discussion about human identity in the 21st century, then he should be thanked for opening that up, too. For the truth of Ferrante’s identity could be the ignition to a fascinating public debate about culture and personality in this new millennium, if we let it be.

What the Ferrante/Raja story fundamentally speaks to is the disjointedness, the weakness, of identity in the 21st century, and how this generates a never-satisfied search for new identities, or ‘identity play’. Ours is an era in which the individual’s identity seems less anchored, less sure, than at any time in living memory. This has nurtured a trend for identity cultivation that can often feel forced, sometimes even desperate, and given to fantasy over experience. Men become women, whites aspire to be black, writers claim to have experienced horrific things they never really experienced, and so on. We’re continually, if implicitly, invited to invent or re-invent ourselves; to make a story of ourselves where a true sense of ourselves seems weak; to make ourselves more ‘real’, ironically through invention.

With hindsight, it seems clear Ferrante/Raja was engaged in a rather unwieldy form of such identity play. In that Paris Review piece she strikingly reneges at the last minute on the plan to meet her interviewers in ‘the neighbourhood depicted in the Neapolitan Novels’, because, she tells them, these are as much ‘places of the imagination’ as they are real, and in real life ‘they are disappointing, they might even seem fake’. Indeed. She also speaks of writing from ‘fragments of memory’. In a piece in Frantumaglia, Ferrante says she is tired of the cliche that the writer must ‘put distance… between experience and story’. The real struggle, she says, is ‘overcoming the distance’ between experience and story. Not only is this surely a hint, unwitting perhaps, that there is great distance between her own experience and the stories she tells — it is also a neat insight into the struggle many now feel between their experience and their story; between who they are and what their identity is, or what they would like it to be.

Literature has, for a couple of decades now, been the site of much identity play. And also of great confusion over who is allowed to tell certain stories and how much personal experience must factor in the creation of literature. This has led to the insistence that only someone who has truly experienced something can write about it, and by extension to some outright deception. There was JT LeRoy, a 1990s American literary sensation who claimed to have survived drugs, vagrancy and being a rent boy: he was actually the creation of the author Laura Albert. James Frey made up much of the backstory to his memoir A Million Little Pieces. Recent Holocaust-related autobiographies have also proven to be written by people conflating elements of personal experience with pure invention. Ferrante’s claims are not nearly as deceptive as those recent scandals, and she has openly said she will not tell the whole truth about herself; but her misleading ‘fragments’ of memoir from a growing-up that seems largely to have been mythical DO speak to a similar dynamic to those more explicit literary deceptions: an attempt to make the author’s identity more ‘real’; to make it fit the story he or she is telling; to ‘overcome the distance’, in Ferrante’s words, between storyteller and story.

A key driver here is the search for authenticity. Authenticity is the holy grail of public and cultural life today. This in itself confirms the very weakness of identity: feeling unreal, people go searching for realness, even to the extent of inventing it. The invention of authenticity, the great contradictory phenomenon of our times, is everywhere. From the purposefully distressed wood table to the hipster hawking of ‘authentic food’, from holiday companies that offer ‘authentic adventures’ to politicians vying for applause and favour in what the New York Times calls the ‘pageant of authenticity’, we crave authenticity, ‘truth in substance’, as the OED defines it, precisely because our experiences and identities feel, in this post-political, post-institutional era, inauthentic, untrue somehow, or at least unrooted. And there is no question that Ferrante’s persona, whether by her own design or more likely through the interpretation of her publishers, the media and her readers, tapped into this inauthentic cultivation of authenticity — the assumption being that her Neapolitan nature made her Neapolitan novels true and real in a way other writers could never achieve.

Indeed, one of the saddest sights since Ferrante’s unveiling has been writers complaining that they’ve been deprived of the right to continue wallowing in this fantasy-authenticity. Gatti’s piece has harmed their romantic relationship with Ferrante’s special Neapolitan literature. ‘I care about not finding out’, says Alexandra Schwartz in the New Yorker. ‘There are so few avenues left… for artistic mystery of the true kind’, she continues. In the Guardian, Deborah Orr says Gatti has ‘violated my right not to know’. Orr says that, inspired by Ferrante’s evocation of Naples, she has visited that city and even the island of Ischia, where two of the central characters of Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels go on holiday. The bizarre complaint being made here is that Gatti has interrupted the experience of authenticity with truth; he has muddied the dream of Ferrante as a seamstress’s daughter with the seeming fact that she’s a Roman teacher’s daughter. Ferrante’s fans are essentially demanding that fantasy be treated as authenticity, an invented story as realness, with no injection of reality. How perverse our understanding of authenticity has become.

To be authentic now is to be the very opposite. In fact, the very search for authenticity makes one inauthentic. In this time of identity confusion and corresponding identity play, the more we seek to ground our identities, to substantiate them, the more we tend to falsify them, or at least embellish them. Where once people knew who they were, or had a pretty strong sense of who they were, now we invent ourselves, usually by reference to the established politics of identity and the therapeutic handbook of the 21st-century West: hence ‘I am’ is replaced by the far more ephemeral ‘I identify as’. In this sense, there’s arguably something positive, even humanist, in the revelation of who Ferrante really is. For it reminds us of the extraordinary power of human empathy, and that you do not have to have experienced something in order to understand or even evoke it. The Ferrante phenomenon seems to have been motored, perhaps implicitly, by the modern dread of ‘cultural appropriation’ — the castigation of anyone who tries to relate to or tell the story of someone from a different racial, cultural or class background. Ferrante’s publishers and media fans certainly seemed more comfortable with the belief, or feeling, that this was a Neapolitan native telling Neapolitan stories, and therefore it was all really real, properly authentic. The report that this is really Anita Raja, who grew up a middle-class Roman, confirms that great literature about aspects of the human experience can be written by people who did not have those experiences.

In everyday life, the struggle to ‘overcome the distance… between experience and story’, to use Ferrante’s words, is a positive one. The more our identity feels rooted — in experience, belief, ideology, work, family, the real — the more substantial it is likely to be. And that is good, a good foundation for living. However, in literature, the struggle to ‘overcome the distance… between experience and story’ can be a negative phenomenon, speaking to the idea that to depict something, to create art from something, you must first have lived it. This is a narrow, even philistine approach. And it can create dishonesty. In attempting to ‘overcome the distance’ between herself and her stories, essentially between Raja and Ferrante, Ferrante appears to have made a few things up and she arguably contributed to the sense that stories must be told by their subjects alone. Let’s ditch the complaining about Gatti’s dirt-digging, and discuss what the Ferrante story really throws up: some pretty profound questions about what it means to be real and what art and literature are for today.

Brendan O’Neill is editor of spiked.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.