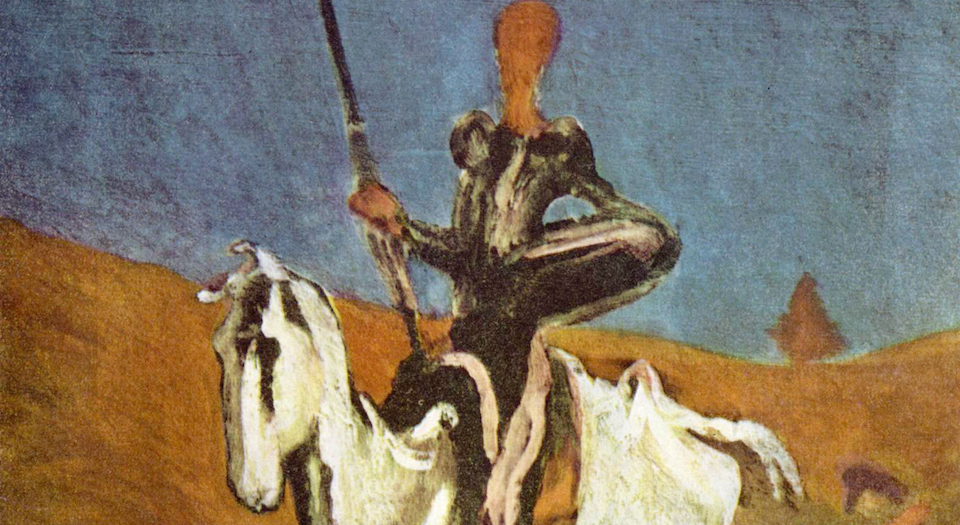

Don Quixote: birth and death of the novel

Cervantes’ classic was the first postmodern novel. Pity it wasn't the last too.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes is regarded as both the first modern and the first postmodern novel in European literature. It is bestowed the first accolade because its protagonist is fully human, possessed with flaws, quirks and doubts. He is the master of his own destiny, for good or ill, who belongs to the realm of the real, like the reader.

The novel represented a break with the romantic, chivalrous tradition that came before. ‘Before Don Quixote, novels were about epic heroes who knew what they were doing and whose principles rarely wavered’, writes Miranda France, author of Don Quixote’s Delusions. ‘Quixote is the first character in a European novel to question his own motives and collude in his own deception.’

Don Quixote is also held as the first postmodern novel in that it flaunts its fictive nature from the outset, constantly rupturing the readers’ willing suspension of disbelief by reminding us that stories – all stories – aren’t true. That is its fundamental premise. It tells the tale of a middle-aged, middle-class Spanish gentlemen, Alonso Quixano, who has become so intoxicated by tales of chivalry that he starts to believe that he, too, is an errant knight: Don Quixote.

After the first part of Don Quixote was published in 1605, another writer, by the name of Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda, brought out his own sequel. Hence when Cervantes resumed the original in 1615, part two of Don Quixote begins: ‘Goodness me, how you must be longing to read this prologue, illustrious or perhaps plebeian reader, expecting to find retaliations, rebukes and railings against the author of the second Don Quixote, the one said to have been conceived in Tordesillas and born in Tarragona!’

The protagonist’s existential crisis becomes more profound as it continues. In chapter 16 of the second part, a traveller exclaims, ‘Now that I know who you are I am even more astonished. Is it really possible that there still are knights errant in the world today, and that there are histories in print of authentic chivalric exploits?’

‘There is much to be said’, replies Don Quixote, ‘as to whether the histories of knights errant are fictional or not’. Towards the end we even have Don Quixote complaining about how Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda represented him.

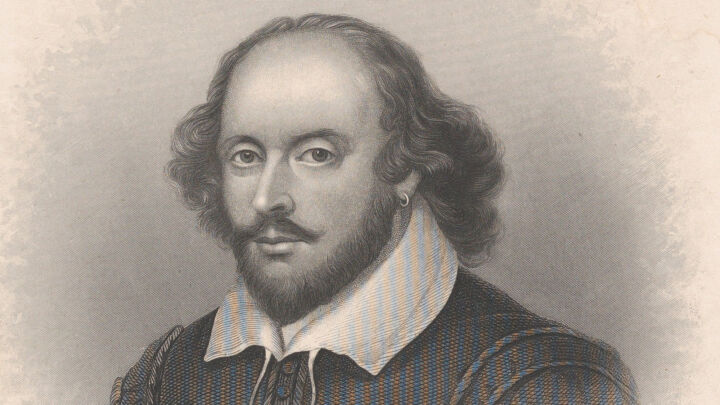

As we mark the 400th anniversary this week of Cervantes death, alongside that of Shakespeare’s, it is worth bearing in mind just how profound and influential the Spaniard’s main opus was. This humane, warm and tragi-comic tale was prescient. Long before the Scream films, The Larry Sanders Show, Extras, Last Action Hero or Being John Malkovich, it took its audience on a playful adventure in which its very nature became satirised and thrown into question.

By breaking the boundaries, Cervantes doesn’t derail his project, for it is far too warm and full of pathos for that. But it’s fortunate for Cervantes’ reputation that he died the year after the second part of his masterpiece was published. For where could he take his knight errant after that? Into a more complex and self-indulgent vortex of self-reference?

There is, it seems, a rule about great authors: whenever their works seek openly to break the boundary between the real and the represented — usually signalled by self-reference – this means that they have reached their best, or are past their best.

James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922) was a case in point. His follow-up, Finnegans Wake (1939), is a masterpiece of gibberish and mischievous wordplay, but it couldn’t be described as a novel. In science-fiction, Valis (1981), by Philip K Dick, which had a version of the author as the protagonist, augured the decline of that writer. More recently, Jonathan Coe underwhelmed us with The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim (2010) with its cop-out ‘it was just a dream’ ending. In all art, self-reference becomes tedious indulgence.

This is the problem with postmodern fiction that breaks boundaries. No matter how entertaining and thought-provoking it can be, it is an artistic dead-end. It collapses upon itself. Cervantes was a master at breaking the rules. But that doesn’t mean anyone can follow his example. It was a splendid joke – 400 years ago. But even the best jokes get less funny the more times they are told.

The myth of self-righteous vegetarians

‘Vegetarianism’, writes the former Labour MP Tom Harris in the Daily Telegraph this week, ‘is the number-one cause of self-righteous sanctimony in Britain today.’

Really, Tom? You think vegetarians are the worst for sanctimony? Not lycra-lout cyclists ‘saving the planet’? People campaigning on behalf of the transgendered? I would certainly put vegetarians below radical students and NHS junior doctors in the self-righteousness stakes.

The stereotype of the ‘self-righteous vegetarian’ may have been valid up to the 1980s, when vegetarianism was considered strange. Those who abstained from meat thus were constantly called upon to justify their lifestyle choice. Meat-eaters didn’t like what they heard in the response – that meat consumption involves killing – hence the creation of the ‘sanctimonious vegetarian’ who said things you would rather not hear.

But vegetarianism is commonplace these days, as is tolerance towards those of us who don’t eat meat. Because it’s no longer an interesting subject, it seldom even becomes a topic of conversation. Not even Jeremy Corbyn makes a big deal about his vegetarianism.

So why does the myth prevail? I fear it’s because of the bad conscience of many meat-eaters who happily eat meat but couldn’t stomach killing an animal themselves. Their bad conscience leads to displacement activities that involve transferring guilt, such as campaigning against foxhunting or against vivisection, or imagining that people only give up meat in order to feel superior.

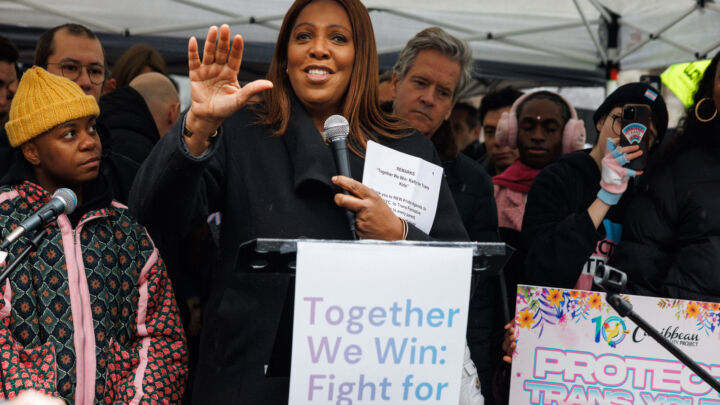

Sneering at North Carolina

Following in the footsteps of Ringo Starr and Bruce Springsteen, the grunge-rockers Pearl Jam have become the latest performers to withdraw from concerts in North Carolina. This follows legislation passed in the US state earlier this year requiring people to use public toilets that correspond to the sex on their birth certificates rather than their gender identity.

If you want sanctimony and self-righteousness, here you are: good old-fashioned disdain of folks in the South coming from the mouths of liberal, metropolitan Yankees. There are many places in the world that treat transgender people worse than North Carolina, including Japan, Russia, China and India. I trust Pearl Jam will not be touring there, either.

There is an obvious way to sort out this tedious, non-issue of public lavatory usage. Simply have toilets with the three categories: ‘Male’, ‘Female’ and ‘Miscellaneous’.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. Follow him on Twitter: @patrickxwest

Picture: Don Quixote, Honoré Daumier.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.