Long-read

Sally Rooney’s regime literature

The Irish novelist has cornered the market in predictable bourgeois leftism.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

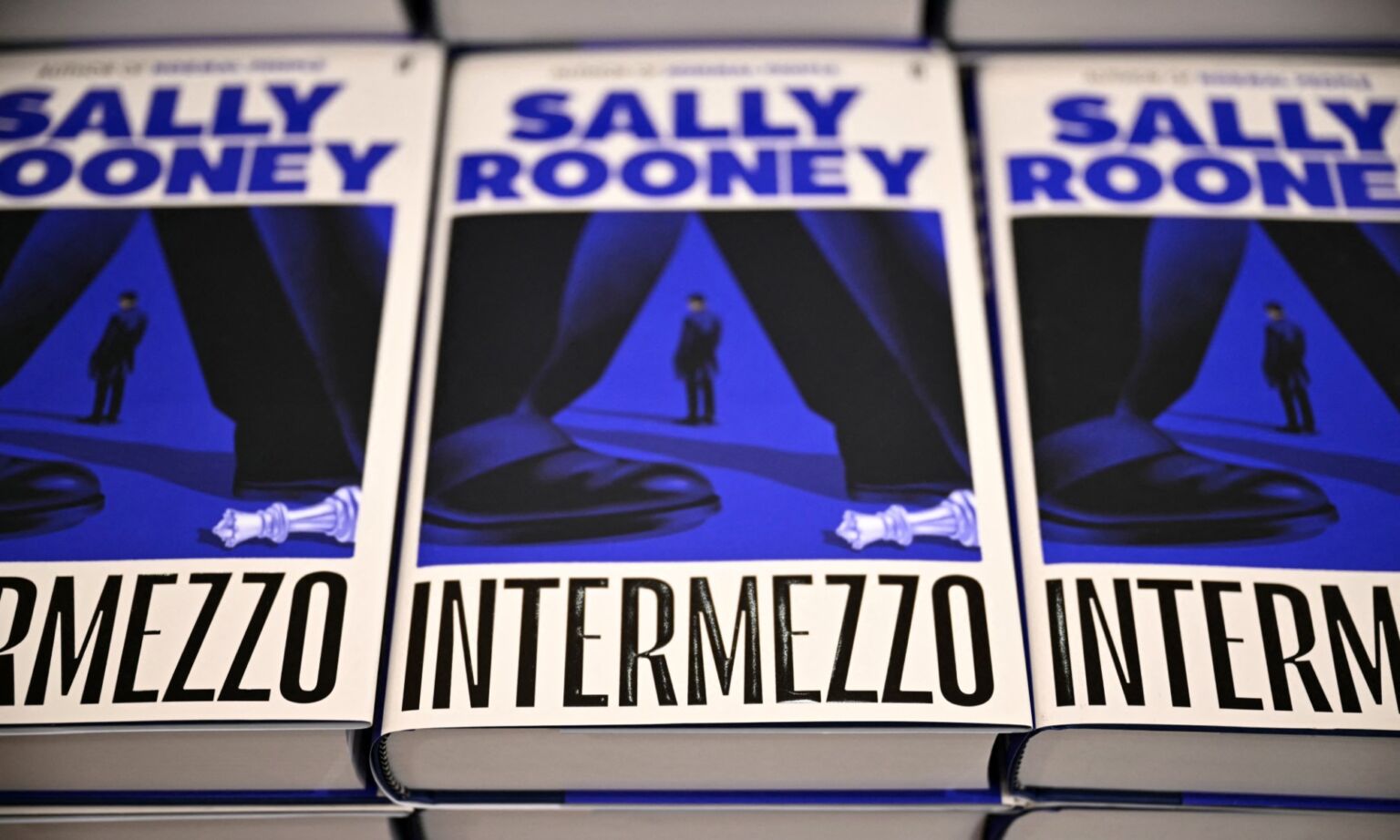

You cannot avoid Sally Rooney when she publishes a new novel. Over the past year in London, the Irish writer’s latest book, Intermezzo, has been as ubiquitous as the ‘Free Palestine’ badges and ostentatiously worn-out sneakers that constitute the uniform of her millennial disciples.

It isn’t hard to understand why this is the case. Indeed, if a public-relations or marketing firm was to design a novel for maximum ‘market penetration’ in an age that doesn’t read, it would look and read precisely like Intermezzo. The characters themselves are close to stereotypes. There is the quiet yet intensely romantic, chess-playing university student – the soft boy. There is the free-spirited, drug-taking and directionless younger woman – the brat. There is the social-justice-warrior barrister with distinctly middle-class problems – which is every lawyer, seemingly, practising in London. Rooney’s characters are young, socially progressive, emotionally vulnerable and beset by depression and anxiety over things like climate change, inequality and the rise of the far right.

In other words, Intermezzo feels less like a product of imagination than the result of extensive market research on the ‘progressive’ middle class – the outcome of Venn diagrams and Excel spreadsheets analysed in consultancy boardrooms. And perhaps most importantly, her books tend to be short and easy to read.

Rooney was born in 1991 in County Mayo, Ireland, where she continues to live. She read English at University College Dublin, distinguishing herself as a student and a debater. What might be best described as the cult of Sally Rooney began in 2017, when she published her first novel, Conversations with Friends.

The phrase ‘literary phenomenon’ may well be aggrandising publishers’ jargon, but it seems appropriate in Rooney’s case. After publishing an essay in the Dublin Review that described her discomfort with the ethics of university debating (she quit because she found it ‘vaguely immoral’), she was approached by one of Ireland’s top literary agents. The manuscript Rooney sent her was subject to bids from seven publishing houses, an auction eventually won by Faber. Conversations with Friends has sold close to a million copies, been translated into nearly 50 languages and was made into a successful television series on BBC Three.

Conversations with Friends is a snapshot of the university lives of Bobbi and Francis – students in their early 20s, housemates in Dublin, former lovers and a spoken-word poetry duo. They strike up a friendship, which turns into a half-secretive ménage-à-quatre, with a married couple in their thirties. Bobbi develops a romantic bond with Melissa, a 37-year-old writer, and Francis has an affair with Nick, Melissa’s 32-year-old husband. Melissa allows the affair to continue on the grounds that it has improved her husband’s mental health, while after a period of estrangement Bobbi and Francis resume the sexual relationship the pair had in high school.

Everything irritating about her work was already present in Conversations with Friends. First, there is a plot that sounds like an interminable, torturous anecdote you can’t help but overhear at a pub. Then there is a pathological absence of humour, combined with a stern, unforgiving millennial morality. ‘No one who likes Yeats is capable of human intimacy’, Bobbi says to Francis at one point. (In an interview after the book was published, Rooney describes the Irish poet as a ‘horrible man’ and ‘really into fascism’.) Every character has a severe mental-health condition or physical disability – Francis cuts herself and develops endometriosis, Nick had a mental breakdown as a result of the stresses of his marriage and Bobbi is the victim of a capricious, alcoholic father. Finally, there is the prose itself, which is devoid of any rhythm and life. The reader is left without a single memorable phrase or passage.

Drawing attention to Rooney’s deficiencies even then would have been an exercise in futility. Evidently, we weren’t dealing with a young novelist – she was just 26 when Conversations with Friends was published – whose work lacked the depth and moral ambiguity that might have come through a more varied life. Instead, it became increasingly clear that we were dealing with a cult. As with the emergence of expressionist painter Jean-Michel Basquiat in New York in the 1980s, it was as though the establishment – in Rooney’s case, publishers rather than art dealers and critics – simply decided that we were in the presence of the new ‘voice’ of a generation. Or, more accurately, they identified a hole in the millennial book market, which they’ve filled with Rooney.

As if to prove that what we were witnessing was a marketing drive, rather than artistic achievement, Rooney’s debut was met with gushing celebrity endorsements. This included Sex and the City actress Sarah Jessica Parker (‘This book. I read it in one day and I hear I’m not alone’) and the supermodel Emily Ratajkowski, who subjected Conversations with Friends to a long analysis on her Instagram page after claiming to have read it ‘in one sitting’. The literary establishment joined in the gushing praise of a completely mediocre first novel, exemplified by a New Yorker interview with Rooney. Quoting a passage from the novel where a party is described as ‘full of music and people with long necklaces’, the journalist intoned: ‘read that sentence and you may never want to wear jewellery again’.

Rooney’s second novel was published a year later. Normal People was greeted with a level of attention one might expect for the discovery of a lost Shakespeare play. The book sold more than three million copies and was longlisted for the Booker Prize. The BBC adaptation, along with launching the career of Irish actor Paul Mescal, has gone on to be streamed more than 65million times. The Times anointed Rooney ‘the first great millennial author’, while her presence in Time magazine’s ‘100 Most Influential People’ seemed to confirm her emergence as a Really Important Person.

Normal People is Rooney’s attempt at a more conventional love story. The protagonists are Connell and Marianne, both students at Trinity College Dublin. They established a romantic connection at high school, when Connell’s mum cleaned the house belonging to Marianne’s wealthy, yet distant and at times violent family (her brother, Alan, breaks her nose at one point). It is a relationship beset by false starts and other romantic interests – Marianne, for example, briefly dates the son of a banker, whose sexual sadism she finds unexpectedly thrilling, and which becomes a feature of her romantic life for the rest of the book. Connell spurns the set in which Marianne unexpectedly flourishes at Trinity because of what we are left to interpret are his working-class hang-ups. The relationship is revived in unlikely circumstances: Connell’s friend dies of suicide, Connell himself develops anxiety and depression and Marianne’s ministrations through this period reignite their sexual chemistry. Things fall apart again when Marianne insists Connell hit her erotically, which he refuses to do. Their status is ambiguous when the book ends after a brief 80,000 words.

Rooney’s two most recent novels – Beautiful World Where Are You, published in 2021, and Intermezzo, published last year – have grown in characters and length. The former is an epistolary-by-email novel, and articulates her trite anti-capitalism more forcefully than any of her other works of fiction. The latter combines pseudo-Marxism with Rooney’s other great interest, personal fulfilment through unorthodox sexual arrangements.

Taken together, Rooney’s novels are better read not as complex dramas, but as didactic, bien-pensant morality tales. Her vision is simplistic, resting on an intractable antagonism between young people who have the ‘correct’, leftish outlook on life, and others – generally men or older generations – who don’t. She takes herself ever so seriously. ‘There is a part of me’, Rooney told the New Yorker after Conversations with Friends was published, ‘that will never be happy, knowing that I am just writing entertainment, making decorative aesthetic objects at a time of historical crisis’.

Yet the distinction between entertainment and ‘historical crisis’ frequently dissolves in her books. In Intermezzo, we find Ivan Koubek, the insular protagonist, telling his older lover:

‘Not everyone has what they need. In terms of world poverty, and all those problems. And then a lot of people have way too much, to the extent that they’re just throwing money around for no reason. Paying people to make graphs, and the graphs could cost anything. The number comes from nowhere. It’s not related to any real resource value. You have – not to get too politicised about it, because I’m not saying it from that side. But you do literally have people going hungry, I know that’s a cliché. Food shortages, it is a real thing. And then you have these tech companies paying me to make a graph. Why? It comes from the wrong distribution of resources.’

Ivan only buys his clothes second hand, and sees nothing but inequality, exploitation and general misery in the economic life of the West. His older brother, Peter, is also fiercely on the left (a quality that, in all of Rooney’s books, marks the characters out as superior), and spends his career as a barrister fighting for moral causes. ‘Sales associate wins discrimination claim over “sexist” uniform’, is how one of his cases is reported in a newspaper that Ivan’s lover happens to be reading. The article reads:

‘“The complainant performs precisely the same workplace duties as her male colleagues, but is obliged to do so in uncomfortable, restrictive and implicitly sexualised apparel, because and only because she is a woman”, Mr Koubek told the tribunal. “The disparity between the ‘male’ and ‘female’ uniforms serves no practical purpose, except as a visual advertisement for gender inequality in the workplace.”’

A shining conscience is one of the few traits that the brothers seem to share. Like most child chess geniuses, Ivan is an introvert with few friends. Peter is handsome, popular and roistering – he has the cool flat, the girls and the job. Yet like all of Rooney’s inventions, he too has his ‘problems’, and is unable to get through the day without a variety of analgesics and alcohol.

Nonetheless, the book has a happy ending. Ivan finds love, somewhat implausibly, with a very attractive woman much older than him – a local teacher who supervises one of his chess competitions. Peter finds fulfilment via a throuple, the members of which are the much younger woman he intermittently sleeps with and his disabled ex (a literature academic), with whom he has a deeper emotional bond. ‘All of them loved, completely needed, for better or worse’, Rooney writes. ‘Inextricable.’ Peter, wracked with guilt,

‘Feels he at once has too much power and too little, enough to make a mess of everything, not enough to sort it out. Is he humiliating them both, she, the other, inflicting on them some terrible exotic pain, for his own selfish satisfaction. Is it shame he feels, that hot blood pounding in his ears…’

In many regards, it is the perfect millennial novel. Every relationship is therapeutic and unorthodox. There is the omnipresence of some kind of disability, either physical or mental. And there is the sense among the characters that society has never been as cruel and unequal as it is in Western Europe in the 21st century.

There is a glaring omission in her oeuvre. None of her novels mention that long-standing staple of middle-class leftist politics – namely, a loathing of Israel. Which is perhaps a little surprising given the war in Gaza has been Rooney’s sole, burning preoccupation in recent months, complete with her high-profile pledge of support for Palestine Action. Perhaps she considers this part of the ‘historical crisis’ too serious a subject to address in one of her ‘entertainments’. For that, at least, we should be grateful. With any luck, her numerous open letters, articles and public statements will spare us a book about, say, an international lawyer who leaves his Dublin polycule to spearhead the prosecution of Netanyahu at the International Court of Justice.

If Rooney is to be credited with anything, it is that she has managed to keep a significant section of a younger generation engaged with reading. For many years this has seemed like a truly impossible task, with even Oxford professors lamenting that the supposedly brightest students in the country struggle to read ‘long novels’. She seems to be one of the only writers standing in the way of Philip Roth’s 2009 prediction, that soon reading a novel would be about as common as reading Latin poetry, coming true.

Yet it seems wrong to classify Rooney’s work as ‘literature’. This isn’t only because it lacks any lyrical beauty or artistic depth. It is also that her books are far more interested in telling you how to live, rather than showing us the truth. She is too certain in her beliefs, too convinced of her moral rectitude. There are no tears or laughter in a Sally Rooney novel, nor does she demonstrate much interest in, for want of a better phrase, the ‘deeper’ questions in life. But then why would she, given she has all the answers?

Rooney is a reminder of two things. Firstly, politics and art rarely mix, particularly in the case of someone as intellectually incurious and ideologically rigid as Rooney. Her novels are closer in spirit to lectures than novels. The second is that compelling art needs to draw, to some degree, on an interesting life – and everything in Rooney’s upbringing, education and personal life suggest an incredibly limited contact with the kind of people and experiences that make a work of literature come alive. In many ways, the same qualities that made her an exceptional student and debater are the same ones that inhibit her as a novelist.

That said, the cult of Sally Rooney is clearly going nowhere. And, as the success of her compatriots Kneecap shows, the market for boring art has never been stronger, so long as it is combined with the ‘correct’ form of prating sanctimony. For those of us who want neither, there will always be the refuge of the second-hand bookstore.

Hugo Timms is an editorial assistant at spiked.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.