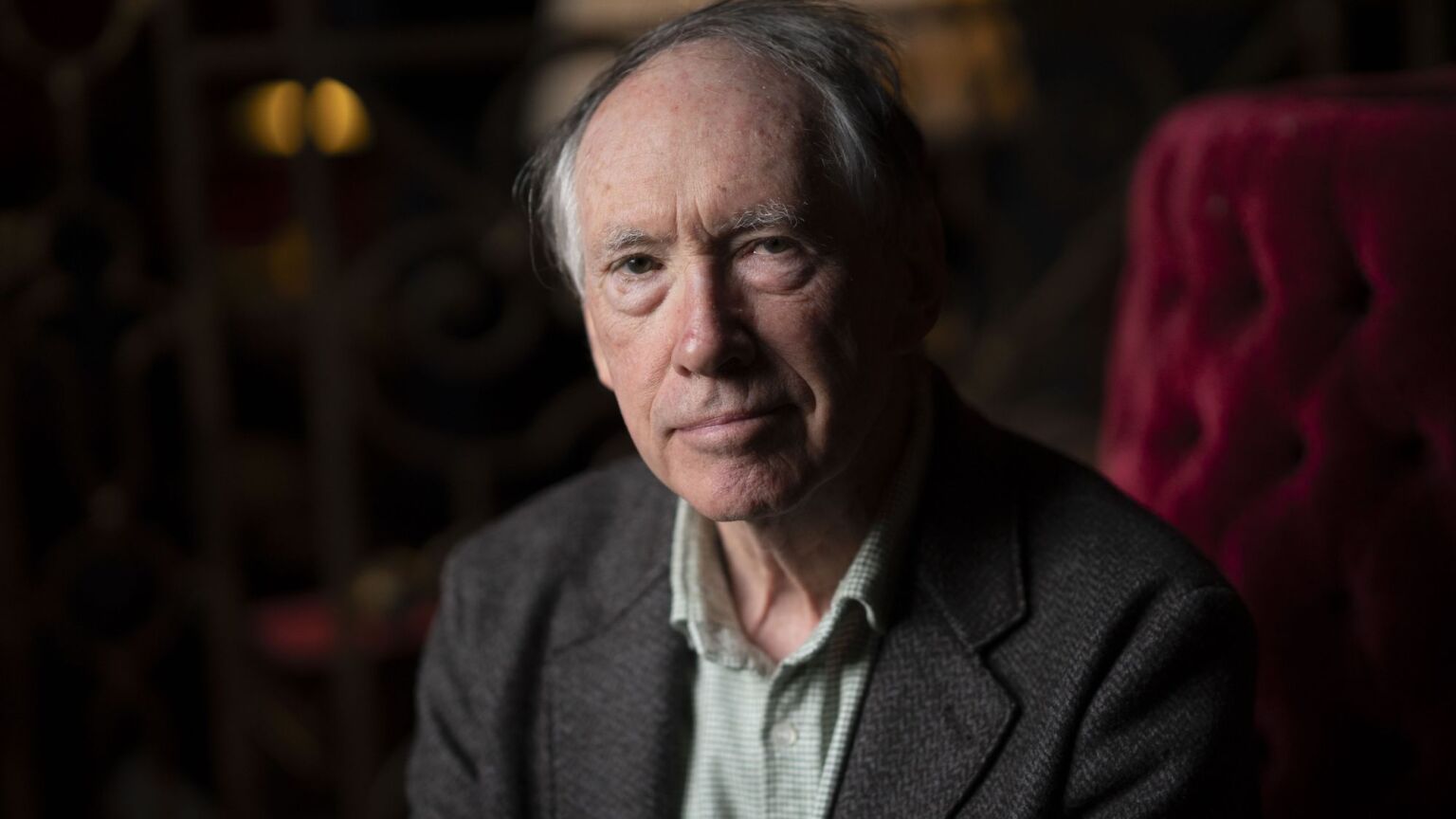

The demise of Ian McEwan

His latest book is about as exciting as a Guardian editorial.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

There has perhaps always been a centrist dad lurking inside Ian McEwan, waiting to break free. His latest novel – set in a future ravaged by climate change – confirms he is now firmly out and proud.

The world of What We Can Know, set 100 years in the future, is one we can hardly recognise. Such has been the impact of rising sea levels that most of England is now submerged. Civilisation’s rapid descent started in 2036, when India and Pakistan went to war because the Himalayan glacier – from which both countries derive their water – dried up. This preceded a disastrous war between America and China over Taiwan and a nuclear exchange in Europe.

As a result of what posterity has come to call the ‘Derangement’, one of the supposedly great poems of the early 21st-century has been lost. In 2119, an academic makes it his life’s ambition to find ‘A Corona for Vivien’, a tribute by the prodigal Francis Blundy to his wife, written in 2014. The academic’s quest takes him on a perilous journey across the sea to Blundy’s former estate in the now sealed-off, uninhabitable Cotswolds.

Politics and fiction almost never mix well. What might have been an interesting book with a worthwhile theme – say, the bond English literature creates with the past – is dampened by the bland, moralising tone of an eco-zealot. We read that Blundy, despite his genius, is a ‘denier to his core’. His wife, after witnessing Blundy’s angry response to a climate protest, reflects somberly that she ‘was familiar with his kind of views. I occasionally read the Telegraph, Spectator and Wall Street Journal among others. Francis was hardly alone.’

McEwan’s superior, finger-pointing tone becomes shrill – almost hysterical – in certain passages. We get an insight into the author’s contempt for our benighted times when one character shares her thoughts on the time of the ‘Derangement’:

‘If I was transported back there, I would loathe it. The stupidity and waste would suffocate me or make me insane… so would the nastiness of social media… How could we overlook or forgive the desolation those times bequeathed, the poisons they left in the ocean, the forests they stole, the soils and rivers they ruined and the Derangement they acknowledged but would not prevent?’

One of the worst things about climate alarmism, along with the insurmountable damage it does to the economy and living standards, is how boring it makes people. That McEwan – a writer capable of producing a book as enthralling as Atonement – can be made to sound like George Monbiot, bewailing the evil of climate deniers who poison the oceans, is proof of how strong this (to borrow McEwan’s phrase) derangement can be.

Like many formerly interesting writers, McEwan is now a proud and (as his latest book reminds us) dogmatic adherent to every establishment orthodoxy. That he has become incredibly wealthy – McEwan was well-placed to write about Blundy’s palatial Cotswolds estate, being the owner of one himself – at least in part explains this. Climate hysteria is, after all, one of the original and most indulgent luxury beliefs. It is hard to conceive of an issue further from the minds of working-class people.

What We Can Know isn’t the first time McEwan has tried to make a political statement in a novel. This book, at least, isn’t as desperate as The Cockroach, published in 2019 as a parody of Brexit, borrowing from Kafka. Jim Sams, the Conservative prime minister, wakes up in Downing Street one morning to find that he has overnight turned into a giant cockroach. It was regime humour at its most banal, as edgy as a Led By Donkeys stunt.

Like many English writers (AC Grayling comes to mind), McEwan lost his mind, and seemingly his sense of humour, as a result of Brexit. Indeed, so outraged was he by the result that he appeared to look forward to the death of his political opponents. ‘By 2019, the country will be in a receptive mood’, McEwan told an audience in 2017 about his hopes for a second Brexit referendum – and that, by 2019, there would be ‘1.5million oldsters, mostly Brexiters, freshly in their graves’. Brexit, he stressed, was motivated by ‘the lowest human impulses, from the small-minded to the mean-spirited to the murderous’ – a description that seems to fit his odious dreams far better than those of the 17.4million people who simply wanted to get out of the EU.

Writers once prided themselves on being against the grain. Where they interacted with politics, it was provocative and iconoclastic. These days, however, there is almost no prominent English novelist whose views don’t exactly mirror the politics of the Guardian and the BBC. McEwan, whose career began 50 years ago with the publication of First Love, Last Rights, is an apt example in this sanitisation of the literary world. The avant-garde writer once known as ‘Ian Macabre’ is now lecturing us on the ‘climate emergency’ and Brexit from his 18th-century manor house, like all of the other establishment scions the rest of us would rather not hear from so often.

Ian McEwan’s demise as a writer is nothing to celebrate. In an era dominated by Sally Rooney, the public’s need for a writer with flair and originality has never been so acute. Whoever that person is, it is not Ian McEwan.

Hugo Timms is an editorial assistant at spiked.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.