I suffer therefore I am

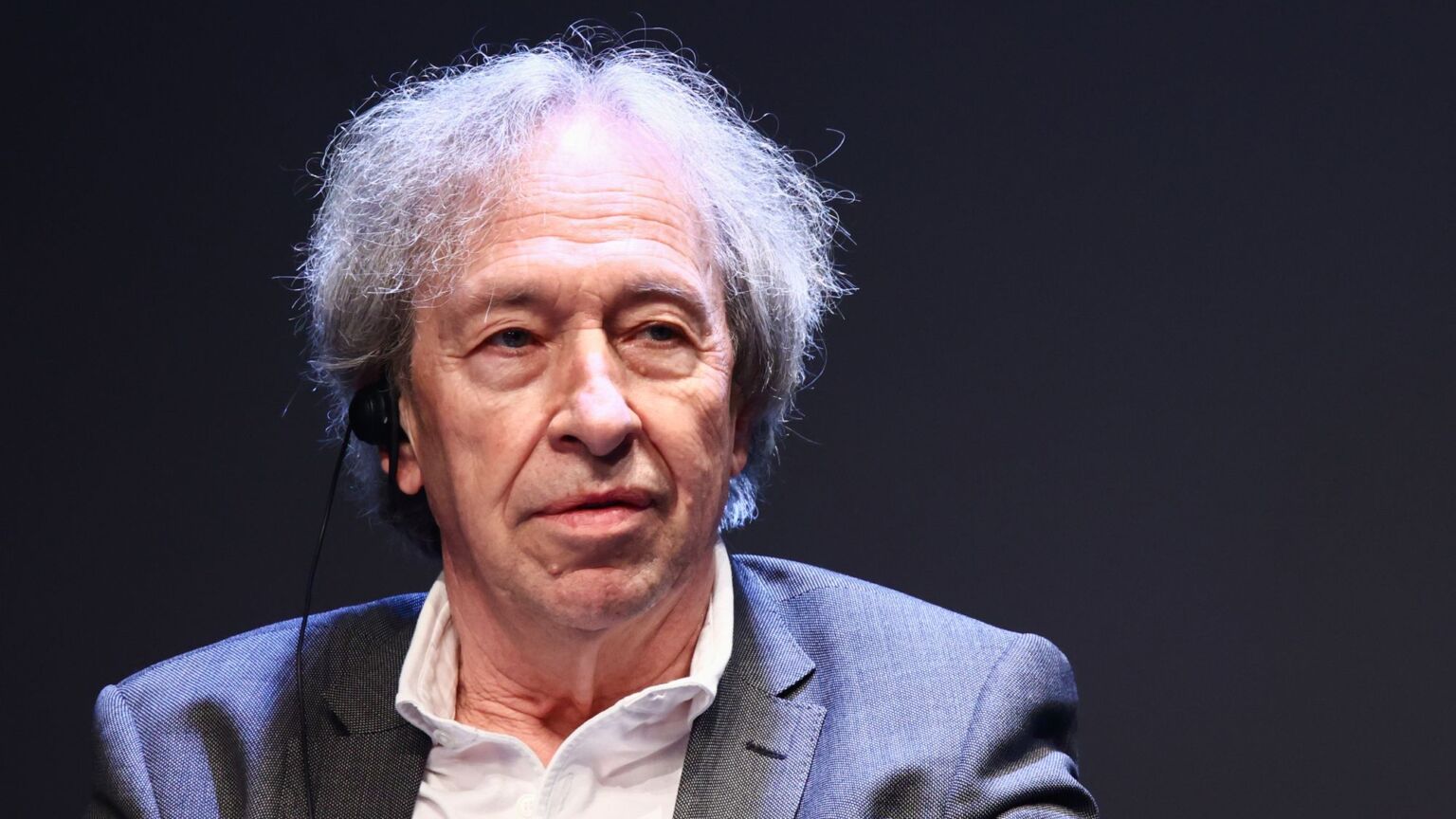

Pascal Bruckner’s latest book offers a devastating critique of modern victim culture.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

It has become common today for some groups to accuse others of being fascists or Nazis, while simultaneously presenting themselves as the most victimised peoples in the world. It’s almost as if assorted aggrieved parties in the world are in a competition as to who has suffered the most, as to who demands the most sympathy. An exaggerated sense of persecution has consequently driven many to claim that their people are the victims of actual genocide.

This has been witnessed most conspicuously in the past two years, with Israel’s military campaign in Gaza routinely labelled as such. For some, even the appropriation of that loaded word hasn’t sufficed. In the spirit of this unspoken contest, last month, the British-born broadcaster Mehdi Hasan claimed that the ‘Gaza genocide is worse than a lot of previous genocides – Rwanda, even the Holocaust’.

It’s not only Palestinian activists who have belittled and debased this word. Many others have been doing likewise.

Serbian nationalists have jumped on this squalid bandwagon. One of its leading intellectuals, politician and writer Dobrica Ćosić, once said that ‘the Serb is the new Jew, the Jew at the end of the 20th century’. Their senior Slav brethren, today’s Russian ultra-nationalists, as embodied in Vladimir Putin, likewise cast themselves as plucky defenders of their people against contemporary ‘Nazis’.

The abasement of the word ‘genocide’ is not new. As Pascal Bruckner writes: ‘Since 1947, the use of this word has snowballed exponentially, and it has been appropriated indiscriminately by all people and minorities who suffer persecution.’

Bruckner is one of France’s veteran conservative intellectuals. His latest book, I Suffer Therefore I Am: Portrait of the Victim as Hero, originally published in his native country last year, seeks to explain the origins of a phenomenon that has now reached epidemic proportions and has an increasing bearing on our politics: the cult of the victim. Why are so many people and groups claiming for themselves the status of the dispossessed, marginalised and oppressed?

Although it’s been thrown into sharp relief in the past two years, Bruckner argues that ‘victimisme’ (victimism) – one of his many neologisms – has been in long gestation. He traces it back to the ascendency of Christianity, with its values having inverted those of Greek antiquity. Borrowing from Friedrich Nietzsche, who first made this argument in his 1887 work On the Genealogy of Morality, Bruckner writes how this new creed rejected the aristocratic values of heroism, stoicism and strength as cruel and callous, and instead venerated the meek, powerless and wretched.

A further factor came into play with the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, which, in removing God as an active agent, rendered man fully responsible for his fate. But that proved an impossible ask. Mankind is incapable of taking responsibility. As Nietzsche summed it up in On The Genealogy of Morality: ‘Someone must be to blame for the fact that I do not feel well.’ As Bruckner concludes, the blame today invariably falls on ‘capitalism, my family, the bourgeoisie, patriarchy, the system’. And while anyone can claim to be oppressed, to be a hero requires exceptional character and special deeds.

Cumulatively and by stealth, there has festered in the West an undercurrent of dissatisfaction and disenchantment. Our present-day obsession with ‘happiness’ has worsened matters, insofar as its ceaseless pursuit only reminds us of what’s wrong with our lives. New technologies have been the final enablers: ‘Cohorts of the “vulnerable” are gathering online to share their despondency and their fears.’ Although he doesn’t specifically blame the rise of woke, its baleful presence is implicit throughout his diagnosis.

The consequences for our politics have been grim. A toxic combination of attention-seeking, self-pity and self-righteousness has let loose a mood of belligerence and vengeance. ‘Victimism is warmongering: the more people feel sorry for themselves, the more they feel justified in punishing those they see as their enemies.’ In Britain 10 years ago, Julie Burchill coined a word for these types: cry-bullies.

We see this bellicosity not only in the politics of black supremacists and revanchist Slavs but also in ‘bitter masculinists’ and radical Islamists. The latter have become experts at victimhood and ‘offensologie’, deploying the cry of ‘Islamophobia’ as a ‘semantic shield’ to deflect criticism. Such is their proficiency in this area that they’ve even managed to invert and pervert history itself. ‘Is the Muslim the new Jew?’, Bruckner asks rhetorically, before outlining how Islamists and their apologists in the West have succeeded in reinventing themselves as the real ‘Holocaust’ victims, with the Jews as the new Nazis.

This development represents the nadir of the sordid, cynical politics of victimhood – as Mehdi Hasan’s recent words unwittingly laid bare. In the words of Bruckner: ‘Many groups and minorities see genocide not as the height of barbarity but as an opportunity to be misfortune’s new elect. The nightmare of Nazism has become the dream of many peoples.’

The proliferation of ‘victimism’ has not only corrupted politics, it has also degraded us as people. This is most apparent in the realm of what he calls ‘neo-feminism’, which in continually apportioning blame to ‘the patriarchy’ leaves little scope for autonomy or agency. The #MeToo movement left a particularly poisonous legacy: ‘Victimising all women means infantilising them, denying them all freedom and responsibility.’

Such sentiments from a white male aren’t likely to go down well in some quarters, but Bruckner is old enough to withstand any bruising comeback. Indeed, that’s his parting message in this bracing, erudite and stark book: be hard. ‘Composure is one of the faces of heroism’, he says. Or, in his own italics: ‘Misfortune is a fact, and there’s no need to make a faith of it.’

We may be the products of our environment, but we have the freedom and the will to escape from history and from our past. Brooding on your problems and always blaming others just makes life worse for everyone.

Patrick West is a spiked columnist. His latest book, Get Over Yourself: Nietzsche For Our Times, is published by Societas.

You’ve read 3 free articles this month.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Help us hit our 1% target

spiked is funded by readers like you. It’s your generosity that keeps us fearless and independent.

Only 0.1% of our regular readers currently support spiked. If just 1% gave, we could grow our team – and step up the fight for free speech and democracy right when it matters most.

Join today from £5/month (£50/year) and get unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content, exclusive events and more – all while helping to keep spiked saying the unsayable.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.