Long-read

The shock, awe and terror of Hiroshima

Why the atomic bombing of Japan still gnaws at the Western conscience, 80 years on.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

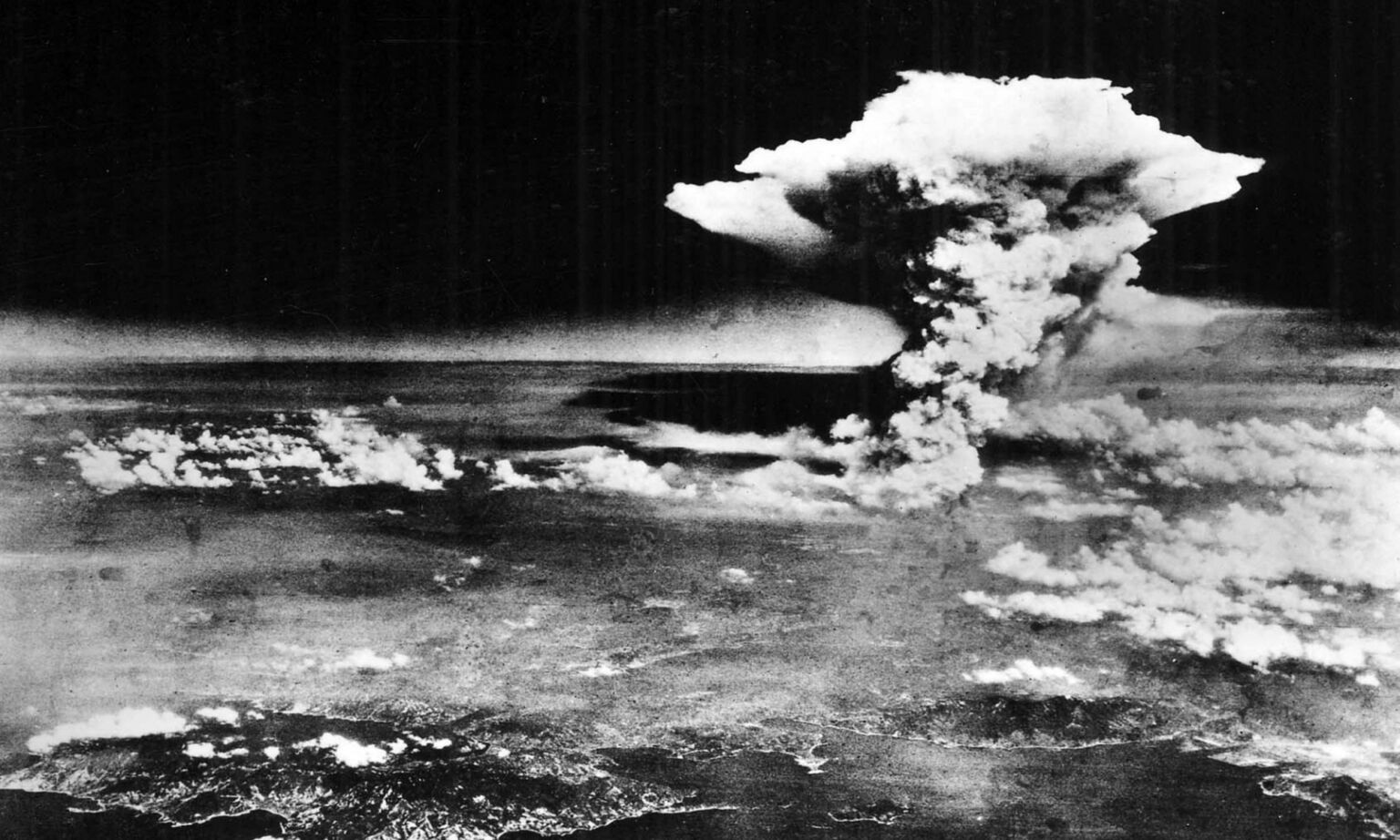

In the early hours of 6 August 1945, US bomber Enola Gay took off from North Field, in the Northern Mariana Islands, and headed towards Hiroshima, a naval port on the south coast of Honshu, Japan’s main island. At 8.15am that morning, Enola Gay unleashed its payload.

This consisted of a 9,700lb atomic bomb, known as Little Boy. Designed like a gun, Little Boy fired a bullet of enriched uranium-235 into a hollow cylinder of the same material, to begin a nuclear chain reaction 1,900 feet above the centre of Hiroshima.

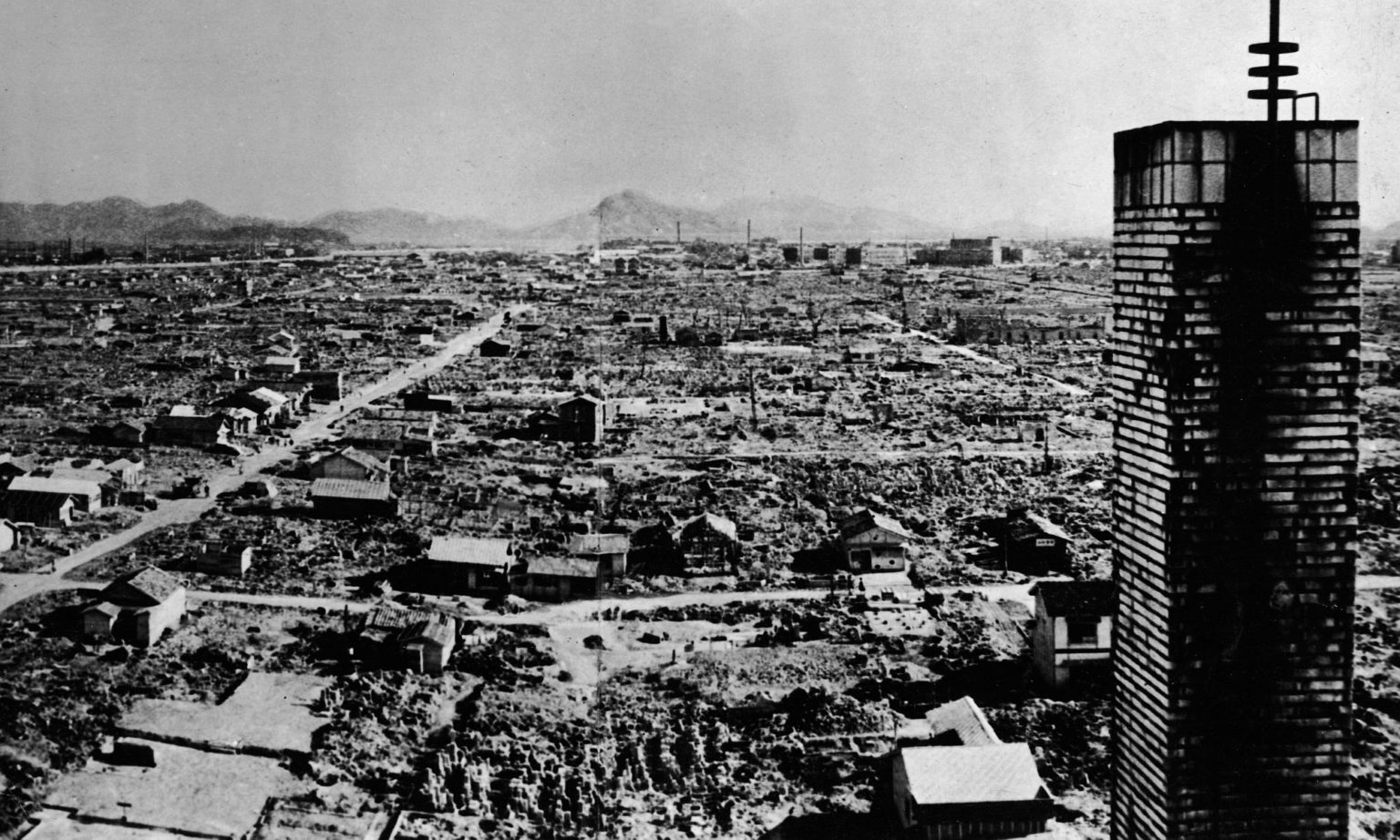

The immediate impact was devastating. Many of Hiroshima’s inhabitants were skinned alive, in part or in whole, by the intense heat caused by the explosion of the bomb. In 1951, the US-Japanese Joint Commission for the Investigation of the Atomic Bomb in Japan calculated that 64,500 people – more than a quarter of Hiroshima’s population – had died from the blast by mid-November 1945, and an additional 72,000 had been injured. Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 30,000 workers conscripted from Japanese-occupied Korea may also have died at Hiroshima.

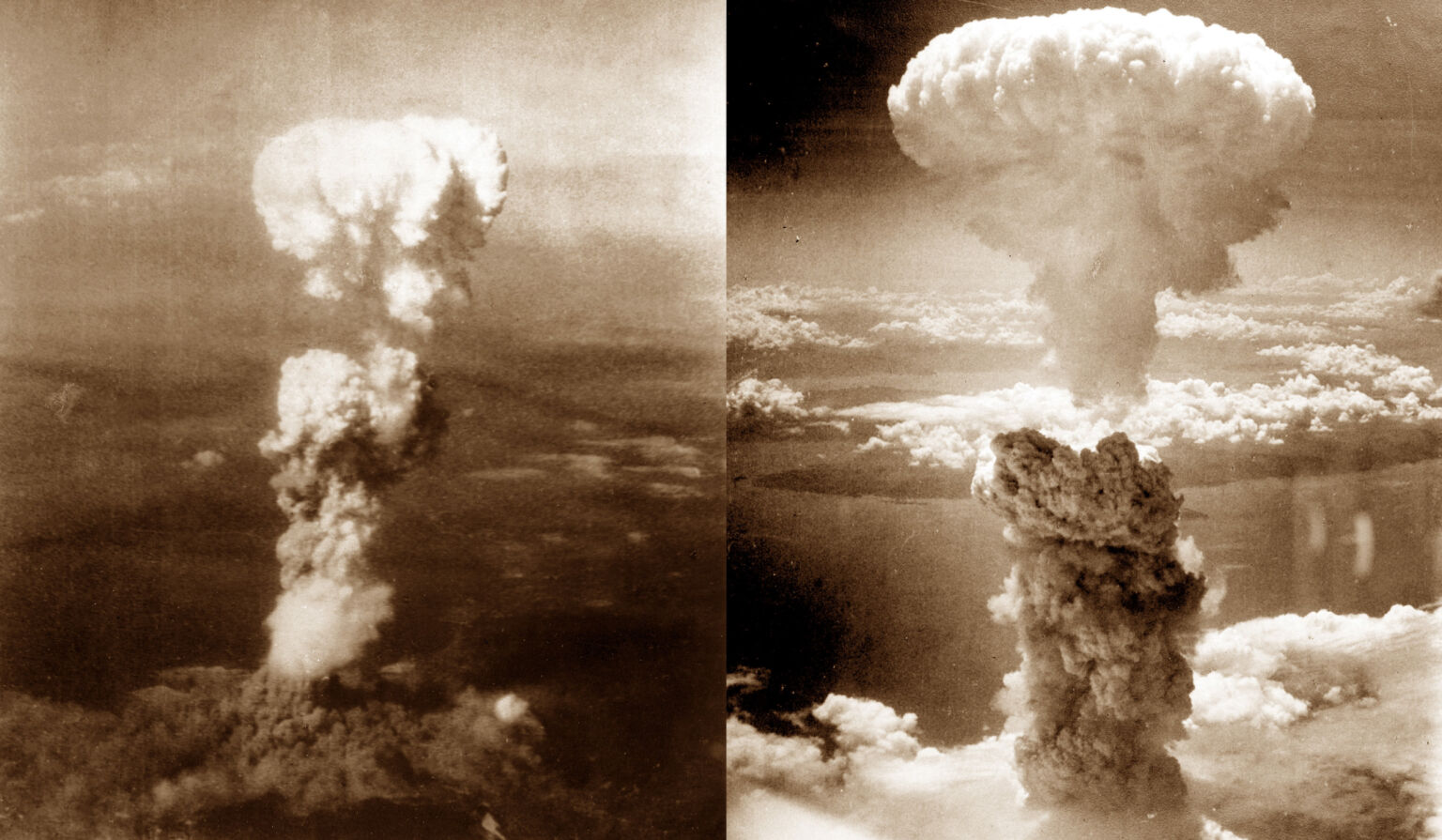

Three days later, on 9 August, the US dropped another atomic bomb on Nagasaki, a city on the island of Kyushu. This killed more than 39,000 – a fifth of Nagasaki’s population – and injured a further 25,000.

The long-term impact of dropping the bombs was horrific. Roughly 400,000 people from the two cities were irradiated and disfigured. Referred to as hibakusha, the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki often faced discrimination when seeking jobs. Their children and even grandchildren still encounter similar problems today.

Eighty years on, amid mounting geopolitical conflict between nuclear powers, it is worth asking what drove America to do something that no other nation had done before or has done since – deploy a nuclear weapon.

For many, the main argument is well established. It was given one of its first public airings by US president Harry Truman in a nationwide radio broadcast on the day of Nagasaki. He said the use of atomic bombs was a reply to the perfidy of Japan’s 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. He denounced ‘those who have starved and beaten and executed’ US prisoners of war. And then came his key argument: ‘We have used it to shorten the agony of war, in order to save the lives of thousands and thousands of young Americans.’ (1)

The argument that the Bomb shortened the war and therefore saved lives is a familiar one. But it’s been disputed, even by many US militarists, including Paul Nitze and his colleagues on the government’s Strategic Bombing Survey. They declared that ‘certainly prior to 31 December 1945, and in all probability prior to 1 November 1945, Japan would have surrendered even if the atomic bombs had not been dropped… even if no invasion had been planned or contemplated’.

Their view was supported by America’s top military commander, General Douglas MacArthur, who had always opposed the use of atomic bombs. He held that Japan would surrender ‘by 1 September at the latest and perhaps even sooner’. Dwight Eisenhower, president from 1953 until 1961, declared the bombings ‘completely unnecessary’. Top brass Chester Nimitz and William Leahy and even the rabid US airforce general Curtis LeMay thought the same, with LeMay saying: ‘The war would have been over in two weeks without the Russians entering and without the atomic bomb. The atomic bomb had nothing to do with the end of the war at all.’

To cap it all, in late August 1945, then secretary of state James Byrnes was reported in the New York Times as saying that Tokyo’s request for Soviet mediation in the war was proof of Japan’s recognition of defeat. He learned of this request at the US-UK-Russian Potsdam conference held from 17 July until 2 August 1945 – that is, before Hiroshima.

Academics Lakshmi Singh and Rahul Tripathi have recently described the bombings as ‘one of the darkest chapters of the 20th century, driven by experimental and political motivations rather than pure military necessity’. In many ways they’re right. Hiroshima was driven less by military imperatives than by two other key factors. First, America needed to flaunt its new, fearful domination of the soon-to-be-postwar world, and so strengthen its rearguard action against the rise of Asia and the growth of anti-imperialist, ‘pan-Asianist’ ideology in the East. Second, America and the Allies were motivated by animosity and contempt towards the Japanese as a race.

The road to 6 August

Hiroshima was in part a culmination of America’s determination to demonstrate its vastly superior military power – especially in the air. In the excellent new book, The Hiroshima Men, historian Iain MacGregor notes that at a White House conference on 14 November 1938, barely six weeks after Britain and France capitulated to Hitler and signed the Munich Agreement of 30 September, President Franklin D Roosevelt made sure that air power was ‘the key discussion’ that day. FDR called for America to double Germany’s annual production figure of 12,000 fighters and bombers, and to be prepared to defend the Western hemisphere ‘from the North to the South Pole’ (2).

By the spring of 1939, the US was concerned not just by the prowess of the Luftwaffe, but also by the superiority of Japanese planes flying over China. The global scope of America’s plans was confirmed when, in November 1939, a committee that included Charles Lindbergh sent a report to congress on what was to become Boeing’s B-29 Superfortress, the enormous bomber that was to deliver the atomic weapons of 1945. Its range spoke volumes about America’s objectives: more than 5,000 miles. So did the sense of urgency that surrounded the B-29 – Boeing was paid upfront for it before it was built, or its components tested (3).

The sums involved were eye-watering. In 1941, the US budget for weapons procurement stood at about three times the $8 billion it had laid out in 1940. It showed that America was intent on reigning supreme.

Indeed, part of Washington’s gameplan in the Second World War was to supplant Britain’s role in the world, and install itself as a more disinterested arbiter of Asian affairs in general and Chinese affairs in particular.

America’s immediate objective was to defeat Japan. Taking a leaf from the RAF’s ‘carpet’ or ‘area’ bombing of German cities, B-29s directed by LeMay firebombed Japanese cities from March to August 1945. In Rain of Ruin, an excellent new book on the atomic bombs, historian Richard Overy quotes a postwar inquest conducted by the British Mission to Japan. It observed that using incendiaries against the population ‘undoubtedly paved the way for the collapse of morale that followed the atomic bombs’. The firestorm campaign prompted Tokyo to put out ‘feelers’ for peace to the US in June 1945. As Overy rightly comments, incendiaries and atomic bombs ‘are often treated as different subjects, but were complementary’ (4).

Evolving attitudes during the course of the war towards the firebombing of cities and towns, which caused immense devastation, paved the way for the use of the atomic bombs. As the atomic physicist, Rudolf Peierls, noted in 1987, indignation may have greeted the aerial bombardment of Guernica in 1937 and Rotterdam in 1940, but Western views soon began to change. ‘The deliberate fire raids on Hamburg [in 1943], Dresden and Tokyo [both in 1945] were considered an acceptable form of warfare. Without this background the atomic bomb raids on Japan might not have taken place.’ MacGregor goes further, writing that the firebombings ‘morally prepared’ the US and its allies for what was to come (5).

The firestorm raid on Tokyo in March 1945 was particularly destructive. Using cluster bombs and napalm, the US killed 100,000 Japanese, laid waste to 300,000 buildings and forced half the population to evacuate to the countryside. Killing similar numbers using an atomic weapon did not seem like such a big leap.

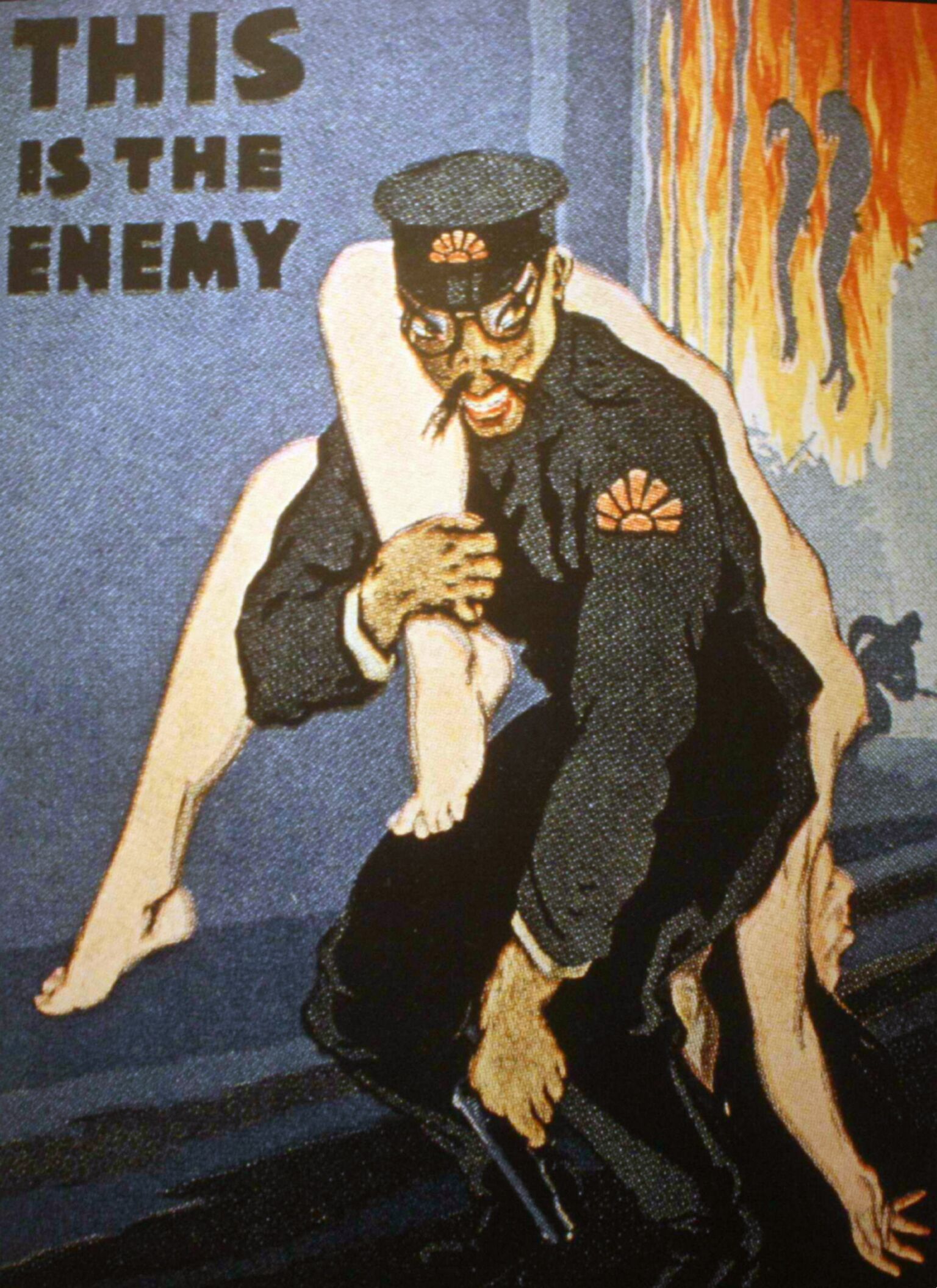

Furthermore, the destruction visited on the Japanese never occasioned the kind of doubts among the Allies that followed similar incinerations in Hamburg and Dresden. Thanks to the Allies’ racial animosity towards the Japanese, every man, woman and child was deemed a fair target. This was clear during the famous island battle of Iwo Jima in February / March 1945, when the Chicago Tribune led with the headline: ‘You can cook them better with gas’. It argued that Japanese dugouts on the island ‘would be an ideal testing ground to determine whether we can render the enemy impotent and materially reduce our own casualties’.

Washington’s uninhibited antagonism towards the Japanese had deep roots, and was fuelled in part by Japan’s rise during the early 20th century. When clinching its victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, the Japanese navy overcame a large Russian force at the Tsushima Strait, which divides Japan from Korea. The following year, a top British military planner described the Battle of Tsushima as ‘by far the greatest and the most important’ naval event since Trafalgar a century before. It was a massive shock to Western self-esteem, and demonstrated Japan’s military strength.

This explains why, after the Russo-Japanese war, America guarded itself with Plan Orange, a series of army and navy war plans for dealing with a possible conflict with Japan. By 1923, that plan included a potential air war with Japan. Five years later, America had drawn up a full war plan, which included intensive air attacks ‘designed’, as Overy says, ‘to make a ground invasion of the Japanese home islands unnecessary’ (6). By 2 March 1943, General Henry Arnold, chief of staff of the Army Air Corps, told a State Department committee that ‘complete and utter havoc-bombing’ should assure ‘the total destruction of the enemy on his own soil’.

America soon learned how badly things were going for Japan. After September 1943, MacArthur’s Central Bureau in Melbourne, Australia deciphered the codes used by Japan’s principal attachés in Europe. As a result, the newly constructed Pentagon knew the details of Tokyo’s defensive formations against a final US assault, as well as about Japan’s leanings toward peace.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, then, were not simply triggered by a desire to avoid American casualties (7). The bombings were the climax to 40 years of planning a response to the threat posed by Japan. They were part of America’s determination to vanquish its Pacific rival, and demonstrate its aerial superiority to the entire world.

But the atomic bomb was different to the firebombing campaigns – not so much in the scale of immediate deaths, but in its terrifying and awesome symbolism.

‘A brilliant luminescence’

After a swift win in the Marshall Islands in February 1944, the US found itself able to attack Japanese targets ahead of schedule. By December, inflation and the worst rice harvest in nearly 50 years had reduced Japan still further. By summer 1945, few Japanese cities were left for the US to bombard. The atomic bomb, therefore, was designed not so much to pile on further devastation, but rather to organise a show for the whole world. As war secretary Henry L Stimson wrote in 1947, the atomic bomb ‘was more than a weapon of terrible destruction; it was a psychological weapon’.

At a key meeting between military chiefs and scientists at Los Alamos, New Mexico, held over 10 and 11 May 1945, minutes record that it was agreed that the Bomb had to be ‘sufficiently spectacular for the importance of the weapon to be internationally recognised when publicity on it is released’. On 31 May, at another key meeting, it was stated that the effect of one atomic bomb would not differ from ‘any Air Corps strike of current dimensions’. However, at that point, Robert Oppenheimer, the so-called father of the atomic bomb, felt compelled to interject. ‘The visual effect of an atomic bombing’, he said, ‘would be tremendous. It would be accompanied by a brilliant luminescence which would rise to a height of 10,000 to 20,000 feet.’ (8) The use of the Bomb was always conceived in spectacular terms.

Covertly delivered by single planes, the atomic bombs were to exterminate thousands through what war secretary Stimson called a ‘coherent surprise shock’. The shock was aimed at the whole world, not just Japan. Moscow was certainly meant to get the message. Leslie Groves, who directed the Manhattan Project and oversaw its security against espionage, said that after two weeks into the job, he never had ‘any illusion’ that ‘Russia was our enemy, and the project was conducted on that basis’.

America was out to impress the whole world. Somewhere, somehow, an enormous number of combatants and civilians had to be burnt to death not over months, nor even in a night’s flames, but in an instant (9).

The Japanese were in some ways the ideal target. They had been conjured up in the Western imagination as a race apart – a cruel, martial and imperialistic people. The racial thinking went both ways. As historian John Dower explained in his classic, War Without Mercy (1986), in both America and Japan, race was the prism through which international relations were viewed (10).

Nevertheless, it was America that had developed atomic weapons. And as Dower showed in a later book, the Allies looked on the Japanese almost as a separate species. During a UK-US Conference on Psychological Warfare Against Japan, on 7 and 8 May 1945, speakers claimed that the Japanese were marked by an ‘inferiority complex, credulousness, regimented thought, tendency to misrepresent, self-dramatisation, strong sense of responsibility, super-aggressiveness, brutality, inflexibility, tradition of self-destruction, superstition, face-saving tendency, intense emotionality, attachment to home and family, and Emperor worship’ (11). Little wonder that, later that month, a top-level meeting involving Stimson entertained the use of poison gas against Japan and authorised tests of mustard gas. In June, ‘mass employment’ of gas, ‘throughout Japan’, was mooted (12).

After 1945, the horrors of the Holocaust discredited racist attitudes in the West. But right up to Japan’s surrender, American animus toward the Japanese was significantly more ferocious than what passes for racism in the US today. Why? Because of Pearl Harbor. Because of Japan’s treatment of American prisoners of war in general and the notorious, 65-mile ‘death march’ it held in Bataan, the Philippines, in 1942 – a forced trek to internment camps, during which hundreds of Americans died of exhaustion, overcrowding, brutality, starvation and disease.

To have these humiliations visited upon Americans instilled the spirit of revenge. While US generals and admirals might have objected to the use of the Bomb on military grounds, Truman, the politician, saw it as an essential lesson to friend and foe alike. World domination, and a world in which the Japanese could never again figure as impudent usurpers, was his aim. To that end, atomic weapons were for him a right and proper means to make these two points.

But America’s victory proved transient. By 1949, Uncle Sam had lost its monopoly of atomic weapons to Moscow, and had lost China to Mao. In retrospect, Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave American imperialism a breathing space – one that it still enjoys today. But they didn’t provide it with the supremacy it wanted.

The Allies attempted to present mass annihilation as an essential, even life-saving act. Eighty years on, it’s an account that no longer endures.

James Woudhuysen is visiting professor of forecasting and innovation at London South Bank University. He tweets at @jameswoudhuysen

(1) Quoted in Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P Bix, Harper Perennial edition, 2016, p502

(2) The Hiroshima Men: The Quest to Build the Atomic Bomb and the Fateful Decision to Use It, by Iain MacGregor, Constable, 2025, p58

(3) The Hiroshima Men, pp59, 61-63

(4) Rain of Ruin: Tokyo, Hiroshima and the Surrender of Japan, by Richard Overy, Allen Lane, 2025, ppX, XI

(5) The Hiroshima Men: The Quest to Build the Atomic Bomb and the Fateful Decision to Use It, by Iain MacGregor, Constable, 2025, p28

(6) Rain of Ruin: Tokyo, Hiroshima and the Surrender of Japan, by Richard Overy, Allen Lane, 2025

(7) Richard Overy notes that the figure of one million killed and injured ‘was suggested by former president Herbert Hoover and became a widely employed statistic to show how high the cost of [US] invasion would be’. See Rain of Ruin: Tokyo, Hiroshima and the Surrender of Japan, Allen Lane, 2025, p74

(8) Quoted in ‘Hiroshima: a strategy of shock’, by Lawrence Freedman and Saki Dockrill, in From Pearl Harbor to Hiroshima: The Second World War in Asia and the Pacific, 1941-45, Saki Dockrill (ed), Palgrave Macmillan, 1993, pp197, 199

(9) As Truman put it in a radio broadcast on 9 August, with typical American pragmatism, ‘Having found the bomb we have used it’. Quoted in Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, by Herbert P Bix (2000), Harper Perennial edition, 2016, p502

(10) See War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War, John Dower, Pantheon Books, 1986

(11) Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Aftermath of World War II, John Dower, Penguin Books, 2000, p284

(12) Rain of Ruin: Tokyo, Hiroshima and the Surrender of Japan, by Richard Overy, Allen Lane, pp74-75

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.