Long-read

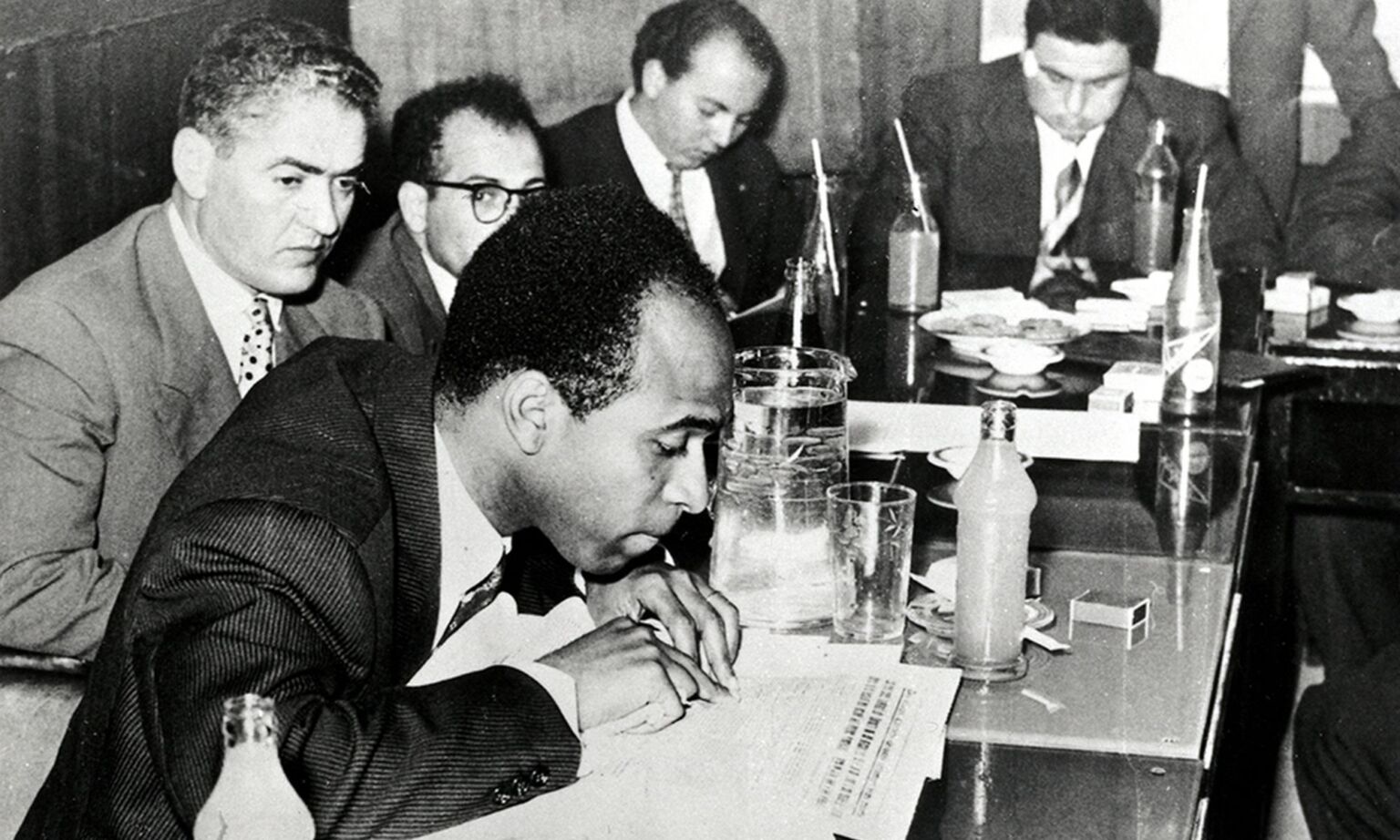

Frantz Fanon’s struggle for freedom

A hundred years from his birth, he is held up as a champion of a racial politics he rejected.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

‘I am endlessly creating myself’, wrote Frantz Fanon in the conclusion to his 1952 work, Black Skin, White Masks. It was a commitment to freedom that underwrote his short, but remarkable life.

Fanon was born on 20 July 1925, in Fort-de-France, the capital of the then French colony of Martinique. His father, Félix Casimir Fanon, a customs inspector, was from a long-line of free, property-owning ancestors. His mother, Eléonore Félicia Médélice, was a shopkeeper. Her lineage reached back to 17th-century Strasbourg, Alsace, a legacy Fanon’s most recent biographer, Adam Shatz, suggests is reflected in the choice of name for their third son, Frantz.

A bright, rebellious boy, Fanon grew up immersed in the putative wonders of French culture and the republican tradition. He may be remembered today for his revolutionary, anti-colonial zeal, but in the early 1940s, he was a youthful, fervent patriot. During the Second World War, the teenage Fanon even went to fight for Charles de Gaulle’s French Free Forces in North Africa and Europe.

This was to prove a disillusioning moment. It was while fighting for France, before living and studying there, that he first encountered himself as the native Frenchman saw him. That is, as a black man, a nègre. And worse, as an inferior, a beastly, animalistic, even cannibalistic threat. He dramatised this painful awakening in Black Skin, White Masks, recalling a particular incident in a train carriage involving a French woman and her young child. The small boy notices Fanon, and yells out: ‘Maman, look, a Negro; I’m scared!’ The small boy didn’t stop there. ‘Maman, the Negro’s going to eat me’, he continued. Suddenly, Fanon felt the weight of a racialising, colonialist vision bearing down up on him. He was experiencing himself not as a man, but as black.

If this was an alienating moment, it was also a catalyst. From that point on, Fanon, who was training to be a psychiatrist in Lyon, seemed to embark on a ceaseless process of self-transformation. A relentless struggle against the reifying, racialising gaze of others. While the existentialist writers whose work Fanon devoured in the 1940s preached a philosophy of human freedom, he practised it. To borrow their jargon, his existence continually and self-consciously preceded his essence.

After the war, he pursued his medical career, practising psychiatry first in France and then in Algeria and Tunisia during the 1950s. He then committed himself to anti-colonial struggle in Algeria, waging war against the very nation he had been willing to die for just 10 years earlier. And in his last years, he turned himself into a champion of an incipient Third Worldism, railing against the colonial crimes of the West – an intellectual development captured in his second published book, The Wretched of the Earth (1961).

He ended his days in a hospital in Maryland, in the heart of the American empire. By the time he died on 6 December 1961, aged just 36, his body wracked by leukemia, Fanon had lived a life true to his credo – ‘I am my own foundation’.

It is a cruel irony then that, in the 21st century, someone so committed to realising our ontological freedom, living authentically as the existentialists had it, should have been turned into what he feared most; namely, a thing. An intellectual brand to be invoked in the name of contemporary identity politics. A ‘postcolonial theorist’ to be quoted in the service of BLM-style anti-racism. A bite-size philosopher of ‘decolonisation’ endlessly cited in identikit anti-Israel diatribes.

Reduced to a set of pithy quotes and biographical factoids, Fanon has himself become a mask to be worn by privileged Western identitarians. They use his scathing analysis of the psychological impact of racism on black people in Black Skin, White Masks to dress up and dramatise their own experiences of (real or imagined) discrimination today – as if Fanon’s experience as a nègre’ in colonial-era France is equivalent to well-heeled middle-class activists’ experience of ‘microaggressions’. And they see in his glistening portrait of the violent struggle for decolonisation in The Wretched of the Earth a glamorous, bloody anticipation of their attempts to remove Geoffrey Chaucer from a university English literature syllabus.

Or worse. Decontextualised, packaged-up and distributed through the seminar room and on broadsheet op-ed pages, The Wretched of the Earth has been turned into a justification for Hamas’s GoPro-ed slaughter and rape of hundreds of Jews on 7 October 2023. The Keffiyeh set point to Fanon’s claim that ‘decolonisation is always a violent phenomenon’, that rebels’ violence is ‘proportionate to the violence exercised by the threatened colonial regime’, and they claim it as an exoneration of the genocidal lunatics of Hamas.

‘The struggle for freedom is rarely bloodless and we shouldn’t apologise for it’, tweeted one typically posh leftist after Hamas militants had slain some 1,200 people. ‘For Palestinians in Gaza and beyond, for the wretched of our shared earth, as for Fanon, “to fight is the only solution”’, wrote another. Again and again over the past two years, we’ve seen the Fanonisation of Hamas. In the words of one American academic, Fanon was ‘helping liberate colonised peoples from the savagery of colonial domination of the sort we see in full throttle in Gaza today’.

Let’s leave aside the absurdity of equating French colonialism in North Africa in the mid-1950s with Israel’s war of self-defence today. The problem here is that they are reducing Fanon’s complex, sometimes contradictory work to a justification for atrocity. They are turning it into little more than a species of contemporary identitarianism, full of wicked white people and evil settler-colonialists. And in doing so they are squeezing the intellectual life out of it. They are erasing precisely the extent to which Fanon challenges present-day leftist orthodoxies.

Take Black Skin, White Masks, which began life as a (rejected) university thesis. Fanon here was not writing about anything close to ‘systemic racism’, or the ‘logic of whiteness’. These fashionable bits of empty jargon treat racism as an all-determining force shaping the world for time immemorial. For a historically conscious thinker like Fanon, they would have been anathema. As he saw it, the specific colonial context was key to understanding racism. ‘The black problem is not just about blacks living among whites’, he writes, ‘but about the black man exploited, enslaved and despised by a colonialist and capitalist society that happens to be white’. It was in a historically specific colonial context, then, that a black man like Fanon, when encountering the ‘first white gaze’, would suddenly feel ‘the weight of his melanin’. That is, it was in a historically specific colonial context that a black man could experience ‘inferiorisation’ and demonisation at the hands of economically and socially dominant people who happen to be white. Racism was a symptom of colonialism, not its cause.

Fanon argues that it is the ‘colonial situation’ that leads to black people experiencing a sense of self-alienation. Focussing on his own experiences in colonial-era Martinique and those of some of his black patients, he argues black people grow up in an environment that promotes a way of thinking and acting that is white – that expresses the sense of superiority of the colonial power. He recalls being taught of the glory of Gauls at school, and the books, comics, movies and advertisements that attributed virtue to all that is white, and evil to all that is black – ‘darkness, obscurity shadows, gloom, night, the labyrinth’.

Little wonder, black Martinicans wanted to see themselves as white French people – indeed, they invariably wanted to become white in some form, to wear white masks. Fanon himself writes of wanting to be treated as a ‘man among men’. Yet, thanks to the fact of Martinicans’ skin colour in the colonial context, the white gaze constructs them as black. It differentiates them, subordinates them. In the white, colonial world, Fanon experiences his body as if it is another’s. Through the white, colonial gaze, he is alienated from himself and his humanity. Of the experience of being a black man in the French colonial context, Fanon writes,’The white world wants him to behave not a like a man, but like a negro’.

What makes Fanon’s account of racism so compelling today is the way in which he ultimately rejects what amounts to a proto-identity politics. This took the principal form in Fanon’s time and place of the ‘Négritude’ movement. Promoted during the 1930s by poet, politician and Fanon’s one-time tutor, Aimé Césaire, future president of Senegal Léopold Sédar Senghor and French Guianan poet and politician Léon Gontran Damas, it amounted, as Adam Shatz puts it, to ‘the affirmation of the values of “black culture”’. It was an assertion of black people’s essential cultural difference – intuitive, ecstatic and in touch with nature – from their European colonisers – rational, utilitarian. It was an incredibly influential movement that, in many ways, shaped a lot of the ethnic-minority cultural nationalism and multiculturalism that was to follow.

Fanon, who knew Césaire well, was not unsympathetic to the cultural separatism of the Négritude movement. In the face of one’s denigration, Fanon himself said that he felt the need to assert himself ‘as a black man’. Sections of Black Skin, White Masks engage in the poetical self-mythologisation of the Négritude movement. Since the black man has always been treated as inferior, writes Fanon, it is tempting to develop a ‘superiority complex’ in response.

But Fanon acknowledges the limits of this form of identity politics and ethnic particularism. Following Jean-Paul Sartre in Black Orpheus (1948), Fanon reluctantly agrees that embracing and celebrating some sort of essential black culture is a form of ‘anti-racist racism’. It is the mere ‘antithesis’ of ‘white supremacy’, ‘a weak phase in the dialectic of progress’. Blackness, like whiteness, will need to abolish itself if we are to achieve genuine, universal human emancipation.

Fanon resented the blithe way in which Sartre dismissed Négritude as almost as a passing fad, especially after he had initially praised it in Black Orpheus. Moreover, Sartre underplayed the necessity of black people in the colonies asserting themselves, as black people, in the face of their denigration. After all, just as the Jew has to stand up for himself as a Jew in the face of anti-Semitism – a point Sartre himself had made – so the ‘nègre’ has to stand up for himself, as a ‘nègre’, in the face of France’s colonial racism.

But Fanon’s commitment to human freedom as a universal always trumps racial thinking. The final chapter of Black Skin, White Masks is a broadside against incipient identity politics. From Fanon’s existentialist vantage point, racial thinking reifies people, turning them into ‘this or that’, into blacks or whites. The gaze of each ‘fixes’ the other. It reduces the individual to a mere expression of his or her respective, petrified culture and history.

To all this, Fanon says no. ‘It is not the black world that governs my behaviour’, he writes, adding that ‘black skin is not a repository for specific values’. ‘The density of History determines none of my acts’, he continues, arguing that ‘I am not a slave to slavery that dehumanised my ancestors’, and ‘I have neither the right nor the duty to demand reparations for my subjugated ancestors’.

‘The black man is not’, he concludes, ‘No more than the white man’. They are constructs of the colonial era. ‘Both have to move away from the inhuman voices of their respective ancestors so that a genuine communication can be born.’ You won’t find that in the Fanon section of a critical-race-theory primer.

In its gritty optimism – in its commitment to humanism and universalism over racialism and particularism – Black Skin, White Masks can seem a world away from the ruthless, raging eloquence of The Wretched of the Earth. Published just before Fanon’s death in 1961, The Wretched of the Earth is marked by his experiences in psychiatric wards in French-occupied Algeria, as well as by his involvement in the Algerian National Liberation Movement (FLN). Having moved there on the eve of the Algerian revolution, which broke out in 1954, Fanon found himself treating traumatised French soldiers by day and broken Algerians at night. He was able to see the brutality of French colonialism at first hand, an experience that led him to resign from the hospital in 1956 on the grounds he could no longer be involved with French state efforts in the country. He was expelled from Algeria the following year, moved to Tunis and became a member of FLN.

Fanon’s tone had certainly changed in The Wretched of the Earth. In Black Skin, White Masks, he had framed the colonial conflict in the existentialist terms of self, Other and the gaze (or ‘look’). Now he was framing the conflict in the far starker terms of one people’s struggle to violently replace another – the ‘replacement of a certain “species” of men with another “species” of men’.

His prior universalism, and his belief in the individual’s capacity to determine their own existence, also appeared to have been dealt a blow. He had once tried to throw off the nightmare of history in the name of individual freedom, rejecting talk of reparations, a black mission and white guilt. Now he appeared to be speaking a language that has become all too familiar. He writes of Europe’s crimes, of it stealing from ‘underdeveloped peoples’, of its wealth resting on the slave trade. The colonised must demand the settlers pay their debts, he writes.

He also appears to directly attack any talk of universalism – of rights, of humanism – as just so much colonialist cant. ‘Leave this Europe where they are never done talking of Man’, he writes, ‘yet murder men everywhere they find them, at the corner of every one of their own streets, in all corners of the globe’. He urges those engaged in anti-colonial struggles to create new societies in their own image, and ‘not pay tribute to Europe by creating states, institutions and societies which draw their inspiration from her’. At these points, Fanon really does appear to be a progenitor of the Third Worldism that went hand in hand with New Leftists’ growing anti-Westernism from the 1960s onwards. Indeed, here he appears to be moving away from the universalism of Black Skin, White Masks and towards the racial, cultural politics that now predominates among bourgeois ‘progressives’.

But appearances can be deceptive. While he rightly condemns European colonialism and the racist practices and attitudes it encouraged, he maintains his appreciation for the intellectual legacy of Europe. The problem is not the universality of certain ideas – of individual freedom, of the dignity of man, of equality. It’s that their universality has been betrayed in colonialist practice.

‘All the elements of the solution to the great problems of humanity have, at different times, existed in European thought’, he writes, ‘but Europeans have not carried out in practice the mission which fell to them’. He ends with a call for the Third World to make good on Europe’s promise, to forge a new history of man – ‘a history which will have regard to the sometimes prodigious theses which Europe has put forward, but which will also not forget Europe’s crimes’.

The Wretched of the Earth was never the straightforwardly anti-Western tract some have since cracked it up to be. It certainly provided a brutal critique of French and European colonialism. But what tends to be forgotten is that it mounted its critique in the name of Europe’s intellectual ideals.

Indeed, Fanon had not really abandoned the core ideas of Black Skin, White Masks at all. He had deepened and enriched them.

In his earlier work, there is a remarkable section on ‘The black man and Hegel’. Based on Alexandre Kojève’s hugely influential 1930s lectures on Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, this section focusses on what makes man human – namely his desire for the desire of another. Man is human, writes Fanon, to the extent he seeks not just to satisfy some immediate need, but also to impose on another a certain sense of himself – as superior, as worthy of being esteemed. The extent, that is, he seeks to affirm himself in the eyes of the other. This tends to be referred to as the struggle for recognition.

Famously, Kojève focusses on the so-called master-slave dialectic, in which the slave, through a long, complex process, fights to be recognised by the master as human. Through this struggle, the slave affirms his freedom, proves himself capable of autonomy. He wins his recognition, while the now ex-master himself finally has another worthy of granting him the recognition he also desires.

But in the colonial context of France, argues Fanon, the struggle for recognition has not really taken place. Masters may have ’emancipated’ slaves. But it is formal recognition, without struggle. The black person has not proven his freedom. He has not affirmed it in a life-risking fight, a struggle for recognition, with the former master. Fanon concludes that too many do not know the price of freedom because they have not fought for it. Meanwhile, the former masters don’t really recognise the formally emancipated as free, regarding him instead with indifference or ‘paternalistic curiosity’.

Fanon is spoiling for a fight. Not for its own sake, but for the sake of that which it proves – namely, his freedom, his humanity. ‘I am fighting for the birth of a human world’, he writes, ‘in other words, a world of reciprocal recognitions’.

The struggle for recognition in Black Skin, White Masks becomes armed resistance to French colonialism in The Wretched of the Earth. That’s why Fanon focusses so much on what looks like the transformative, ‘world-shaking’ power of violent struggle. Because as he still sees it, it is through the struggle that those fighting for independence prove their freedom, affirm it in the world and in the eyes of their colonial opponents. The violent struggle transforms ‘spectators crushed with their inessentiality into privileged actors’. Into people becoming and proving that they’re free.

Despite its popularity among identitarian leftists, The Wretched of the Earth retains in large part Fanon’s belief in a future free of racial categorisation and identity politicking. A future of ‘reciprocal recognitions’ of others’ freedom, others’ humanity. Indeed, its concluding chapter is replete in calls to ‘humanity’, and hopes for a ‘new history’, for ‘new men’. ‘What we want to do is go forward all the time, night and day, in the company of Man, in the company of all men.’ He was always concerned with human liberation, not racial assertion.

But this today appears to be a forgotten legacy. On what would have been his 100th birthday, Fanon is arguably more famous than ever. The Wretched of the Earth is now a must-have for every privileged BLM-supporting, keffiyeh-wearing dullard going. His thought has been boiled down to memeable units, and circulated online by the anti-Israel set. And yet for all his cultish fame, Fanon’s key beliefs and ideas continue to be ignored.

The Cameroonian philosopher, Achille Mbembe, said of Fanon that he envisioned ‘a world finally freed from the burden of race, a world that everyone has the right to inherit’ (1). In these divided, identitarian times, it is a world that seems further away than ever. Fanon, as flawed a thinker as he was, can still point us in a more genuinely progressive direction.

Tim Black is associate editor of spiked.

(1) Cited in The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon, by Adam Shatz, Apollo, 2024.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.