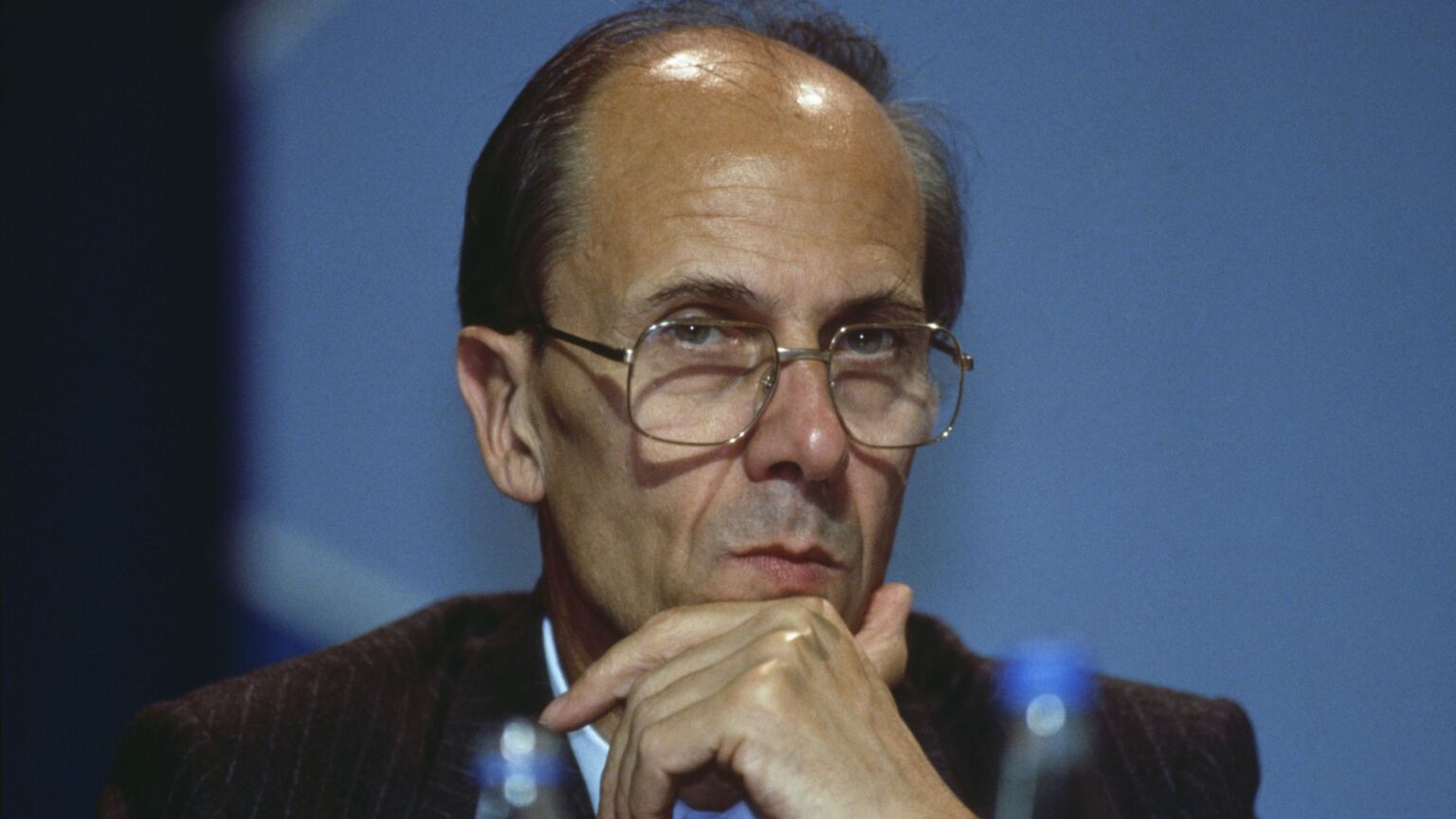

Norman Tebbit and the pull of working-class Toryism

The Tory stalwart spoke to patriotic, aspirational working-class voters who Labour could never reach.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

With the death of Norman Tebbit aged 94, it feels like we’re seeing the final passing of an older and very different type of politician – unvarnished, confrontational, brutally honest and utterly indifferent to the vapid mores of technocrats.

For many, Tebbit will forever be caricatured as Margaret Thatcher’s street-fighting enforcer. He was the ‘Chingford skinhead’ who, in a succession of cabinet positions during the 1980s, gleefully wielded the cosh against trade unionists, leftists and anyone else who got in his way.

But that cartoonish image obscures what Tebbit really represented – a strain of working-class Conservatism the left never understood, and which today’s Tories have all but abandoned.

Tebbit first entered parliament in the 1970 General Election, as the Conservative MP for Epping. This may have been Winston Churchill’s old seat, but Tebbit was no product of the Tory establishment. Born in 1931 in Ponders End, Middlesex, he was the son of a repairman and worked as a pilot, first in the Royal Air Force, then with British Overseas Airways Corporation. He didn’t walk into politics through elite networks – he pushed in through sheer will and shopfloor experience. His worldview was shaped not in the quadrangles of the University of Oxford, but in the cockpit and in the housing estates of postwar London.

That experience lay behind his most famous comment. When asked about unemployment in the early 1980s, he recalled how his own father, during the Great Depression, had ‘got on his bike and looked for work’. It was a phrase endlessly misquoted and weaponised by critics.

What the left never grasped was that Tebbit wasn’t trying to be cruel to those who had lost their jobs. He was talking about individual agency, about people’s own capacity to improve their lives. He loathed the defeatism of the left which seemed to encourage and fuel welfare dependency. And he despised the trade-union barons who, in his eyes, shackled working people and deprived them of hope.

Labour may still have claimed to have connections to the working class during the 1980s. But its leading figures and supporters never knew what to make of Tebbit. They saw him as a brute, and dismissed him as a Thatcherite attack dog.

They couldn’t see that Tebbit spoke to a swathe of blue-collar voters they couldn’t reach. He appealed to the patriotic and aspirational, to those who were suspicious of state handouts and furious at what they saw as the cultural vandalism of the 1960s. His politics resonated at a cultural as well as an economic level. Working-class Toryism was not a contradiction in terms to these voters – it was their political home.

Tebbit was contemptuous of the counterculture of the 1960s. While the left waxed lyrical about free love and liberation, Tebbit talked of ‘that fading, grey, grimy little decade, that third-rate decade of psychedelic dross and casual violence’. For him, the permissiveness of that decade unleashed forces that gnawed away at Britain’s moral fabric.

He famously riled Britain’s liberal establishment in 1990 with his ‘cricket test’ jibe, questioning the loyalty of immigrants who cheered for foreign teams over England. It was condemned as crude and inflammatory. But it touched on a growing anxiety about Britain’s lack of social cohesion – a subject few politicians since have dared to address with such brutal clarity.

Tebbit’s story is also a story of personal resilience. In 1984, he and his wife Margaret were badly injured in the IRA bomb attack on Brighton’s Grand Hotel during the Conservative Party conference. Tebbit was pulled from the rubble, battered but alive. Margaret was left permanently paralysed. Many would have walked away from public life, but Tebbit didn’t. He returned to frontline politics, serving as party chairman and remaining one of Thatcherism’s most recognisable standard-bearers. At the same time, he became his wife’s lifelong carer.

The left persisted in portraying him as some sort of Tory thug. But after the Brighton bombing, what he really showed was his loyalty, grit and sheer endurance.

Tebbit left the cabinet after the Tories’ 1987 General Election victory so as to be able to dedicate more time to Margaret’s care. He stepped down as an MP in 1992, and was made a life peer, Baron Tebbit of Chingford.

During the 2000s and 2010s, he continued to make his views known on certain issues, from the EU to overseas aid. If he seemed out of place during David Cameron’s tenure as Conservative leader and prime minister, it’s because Cameron’s Tories were everything Tebbit despised – slick, lightweight, obsessed with PR stunts and social liberalism. Cameron’s attempt to ‘detoxify’ the so-called Tory brand, from his championing of gay marriage, multiculturalism and environmentalism, was anathema to Tebbit. He saw it as a betrayal of Conservatism, and derided Cameron and his ilk as the ‘Notting Hill set’ – a privileged group of posh boys painfully estranged from the lives of the voters Thatcher and Tebbit had once won over.

Tebbit’s criticism of the Tories’ trajectory may have been derided by many pundits at the time, but it has since started to look prescient. He warned that the Tories’ abandonment of their core values, based on nation, family and work, would alienate voters. In many ways, the Brexit vote in 2016 and Boris Johnson’s subsequent electoral victory in 2019 were vindications of Tebbit’s view of Britain’s patriotic and culturally conservative majority. But even Johnson, for all his populist stylings, couldn’t match Tebbit’s consistency or resilience. Johnson’s politics were opportunistic – Tebbit’s were forged through experience and struggle.

In today’s political culture, where every utterance is pre-approved by focus groups and politicians grovel for forgiveness at the first whiff of controversy, Tebbit’s bluntness feels almost refreshing. He didn’t care about your outrage, because he thoroughly believed in what he said. Even those who disagreed with him could respect that. It’s a quality that is in strikingly short supply today.

It might be tempting to see Tebbit’s death as the final breath of a bygone era. But this would be a mistake. The forces Tebbit represented – self-reliance, patriotism and working-class conservatism – haven’t vanished. They’re still there, only waiting for an outlet.

Neil Davenport is a writer based in London.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.