Elon Musk’s party for oligarchs

The America Party is a cult of no personality that has nothing to offer to voters.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

Just what America doesn’t need – another party dominated, and this time even started, by oligarchs. SpaceX owner Elon Musk may be able to design rocket ships, but his understanding of politics and public opinion is below elementary-school level. His plan to launch a new party, the America Party, seems largely delusional.

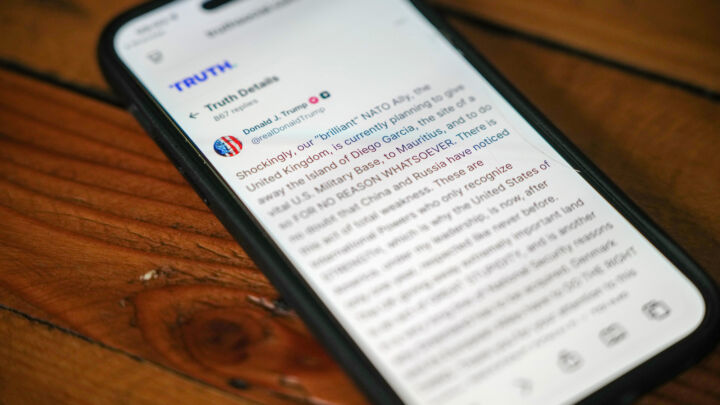

Musk had been teasing the idea of a new, third party for several weeks, following his spectacular falling out with US president Donald Trump. Musk, who had previously led the White House’s efforts to cut public spending at the Department for Government Efficiency (DOGE), was dismayed to learn of Trump’s plans to massively boost spending in his flagship One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Last weekend, Musk announced the creation of the America Party, which he claims will be able to defeat the Republican-Democrat duopoly and represent the ‘80 per cent’ of Americans ‘in the middle’. Billionaire Mark Cuban and financier Anthony Scaramucci have offered to help get the party going.

Musk may be the most successful entrepreneur of his generation, but he is not remotely popular, with 55 per cent of Americans disapproving of him. Nor is the idea of oligarchs funding political parties well received. According to Pew Research, 80 per cent of Americans believe wealthy donors have too much power – and they are right. In 2024, election spending in real dollars is estimated to have been two to three times higher than two decades ago. Some 40 per cent of all political contributions, according to Jacobin, come from the wealthiest one per cent.

The US Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United ruling, which essentially prevented any real restraints from being placed on campaign spending, accelerated this pattern. This is hardly just a Republican gambit. Until recently at least, the main beneficiaries of so-called dark money have been Democrats, getting big paydays from backers like Microsoft’s Bill Gates, LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman and Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff. These donors helped Kamala Harris raise well over $1.5 billion – the highest figure in history – for her losing presidential campaign.

Americans once admired the tech oligarchs but increasingly find them objectionable and scary. Between 2018 and 2021, Facebook, Amazon and Google all suffered a large-scale loss of confidence. They are now even more unpopular than the hated mainstream media.

Let’s face it. These guys are not upstarts anymore, but increasingly monopolists. Google and Apple account for nearly 90 per cent of all mobile-browser use worldwide, while Microsoft, Android (Google) and iOS (Apple) hold roughly the same share of all operating-system software. Like Wall Street bankers, their power epitomises the relentless concentration of the economy that many Americans instinctively fear.

Those on the Democrats’ left flank, unlike their dunderheaded and oligarch-dependent moderate opponents, know an opportunity when they see one. Responding to this sentiment, Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez have launched a ‘fighting oligarchy tour’, proposing that Trump-aligned oligarchs are the precursors to a new authoritarian – even fascist – regime. Hypocrisy alert: the Democrats’ recent ‘no kings’ campaign against Trump was largely funded by the ultra-rich, led by an heiress of the Walmart fortune.

In this atmosphere, I doubt that many will rally to Musk’s new party. Third parties in America are generally built around personalities who can run for president – such as Teddy Roosevelt and Ross Perot – which Musk is disqualified from doing, having been born in South Africa. More importantly, third parties are most often driven by grassroots anger from classes who feel ignored by both parties. Prime examples vary from the agrarian-oriented Populists of the early 20th century, the Socialists under Eugene Debs, Robert La Follette’s Progressive Party, as well as the George Wallace movement in the 1960s and early 1970s.

A far more proven strategy lies in penetrating an existing party, as Trump has done with the GOP and as liberals managed with their takeover of the Democratic Party in the 1930s. In each case, these challengers responded to popular calls against perceived elite evils. Musk’s campaign, in contrast, is entirely astroturfed and is built around a cult of no personality. It’s unlikely that disgruntled voters could identify with a super-rich South African with numerous offspring from numerous unmarried women.

Nor is it likely that Americans are ready to flock to Musk’s libertarian agenda of shrinking government services. Two-thirds of voters, according to a recent Pew survey, believe the economic system needs a large-scale overhaul. Over 60 per cent of voters overall – including over 40 per cent of Republicans – favour raising taxes on corporations and the wealthy. Cutting the bill for social security and Medicaid may well be necessary to repair America’s public finances, but the very thought of it is widely opposed throughout the middle and working class. In fact, rising inequality and general fear of downward mobility could have the effect of boosting support for expanded government and greater redistribution of wealth. Musk’s libertarianism, if not openly elitist, offers a dim future for the plebeian classes.

Far from being exemplars of the vitality of democratic capitalism, the oligarchs are now better known for suppressing opportunity. Amazon is accused of mining sales data from independent sellers to launch competing products under its own brands. Google has been fined billions of dollars for giving preferential treatment to its shopping service on its search site and for manipulating browser extensions to drive customers from rival products. Small businesses – and consumers – have to pay for services only these monopolies can supply. As Michael Lind has noted, these are exemplars of ‘tollbooth capitalism’ – firms that receive steady revenues on transactions for which most consumers have no alternative.

Any party for oligarchs is unlikely to have much time for the needs and wants of the masses. The rightist tech elite celebrates the likes of Curtis Yarvin, who favours ending democracy and imposing a tech-led monarchy. Like the eugenicists of the last century, he favours measures to keep down those deemed inferior. For good measure, he seems also to have a soft spot for slavery, suggesting blacks might have been better off without abolition.

Peter Thiel, an influential figure and funder on the tech right, and longtime Musk ally, warns darkly of ‘a deadly race between politics and technology’, with technology deemed superior to democracy. Thiel embraces the notion that the cognitively and genetically gifted represent the future of society. Musk seems to be on board with such a vision, too.

In the broadest sense, Musk epitomises not so much an ideology but a technocratic mindset that has little political appeal outside fellow oligarchs and some of the humans they still employ. Most do not hold ordinary people in high regard, notes Gregory Ferenstein, who interviewed 147 digital company founders. At best, they expect them to be put on the dole, as the devices created by the elites make them redundant. This is one reason why so many tech oligarchs support a universal basic income – a policy embraced by Mark Zuckerberg, eBay founder Pierre Omidyar, Open AI’s Sam Altman and, of course, Elon Musk.

America’s two-party system is certainly flawed, its ballooning debt remains a vital issue, and the federal government may well need to cut back on some of its social spending for fiscal reasons. But a political party designed by one of the world’s richest men that sets out to cut public spending is going to be a tough sell – not least as his own fortune has been largely financed by government subsidies. Most likely, Musk’s latest brainstorm will be abandoned by its attention-deficient architect once he finds a new, shinier object of his desires.

Joel Kotkin is a spiked columnist, a presidential fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University in Orange, California, and a senior research fellow at the University of Texas’ Civitas Institute.

£1 a month for 3 months

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked – £1 a month for 3 months

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Exclusive January offer: join today for £1 a month for 3 months. Then £5 a month, cancel anytime.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.