Long-read

The reactionary turn against nuclear power

How disillusionment with modernity birthed the anti-nuclear movement.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

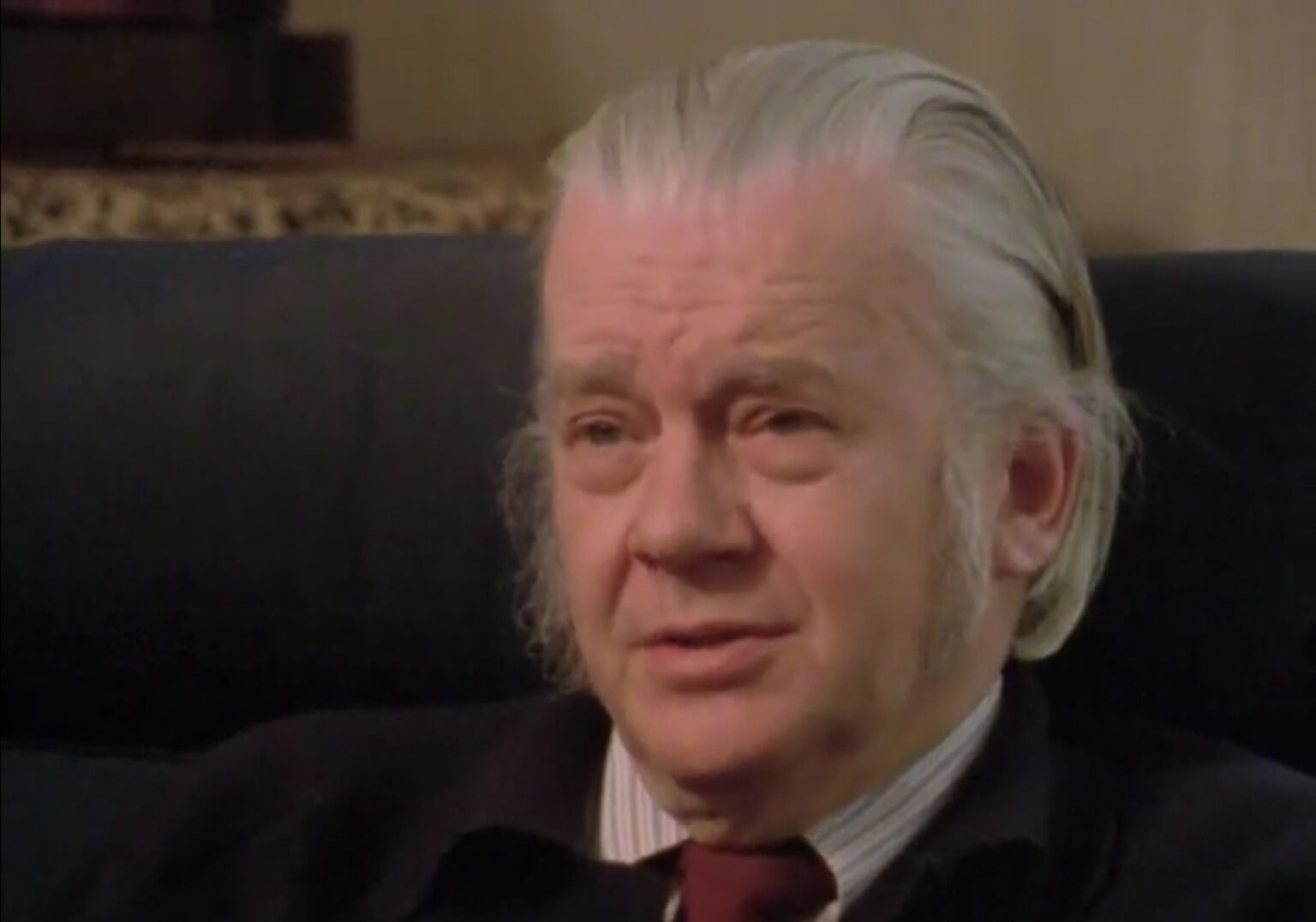

Following its spectacular and devastating entrance on to the world stage during the Second World War, nuclear power had been tamed and gloriously resurrected during the 1950s as a radically new way to deliver energy. While reflecting on his lifelong career in the nuclear field, a former Manhattan Project lab worker noted that he and his colleagues were ‘tainted by the bomb’ (1). They all felt better thanks to the nuclear power plant. ‘What could be nobler’, he wrote, ‘than providing the world with an ultimate energy source?’.

Well, not everybody appreciated it. Those who opposed nuclear power during the 1960s and 1970 challenged the establishment. They distrusted science, politics and big business, and they would no longer keep quiet. They wanted to have a say in everything: on capitalism, war and oppression in general. Every opinion counted, especially their own.

When it came to nuclear power, supporters and opponents talked past each other. One group believed nuclear power was clean and safe, while the other thought it dirty and risky. Both sides acted as if they had knowledge, whereas the other side only had ideology. They made the same accusations: their adversaries were thoughtless, superficial, short-sighted. In the public debate, the opponents of nuclear power won. They showed their emotions and appealed to those of others, while nuclear advocates came across as detached accountants.

This clash illustrated a growing gap between the scientific world and literary intellectuals. The divide was identified as early as 1956 in a New Statesman essay by a man who had affinity with both sides: Charles Percy Snow, better known as CP Snow. He had studied physics, worked under Ernest Rutherford and served the British government as a scientific adviser. Everyone knew him as a writer of popular novels.

In ‘The Two Cultures’, considered to be one of the most influential lectures ever, Snow stated that there was a deep mutual distrust between science and the humanities. Between the two cultures, the relationship was one of hostility. Above all, there was a lack of understanding. Snow was annoyed that the scientists among his friends even spoke of Charles Dickens as if he were an obscure experimental author. Of the writers among his friends, he found it unacceptable that they had about as much insight into modern physics ‘as their neolithic ancestors would have had’.

Snow noticed that literary intellectuals were gaining influence in politics. This worried him. It is dangerous, he warned, when policy is increasingly made by people with an interest in the classics but not in the natural sciences, a discipline that had arguably given people richer and healthier lives. What Snow did not and could not see was that it was precisely this increasing prosperity that would soon be challenged.

One of the first to question this idea of progress also worked for the British government, at the intersection of politics and industry. He too wrote eloquent commentaries. And he too became known by his initials. EF Schumacher was born in Germany, but moved to England when the Nazis were preparing for a war in which his brother-in-law, Werner Heisenberg, was put in charge of developing Hitler’s atomic bomb.

In his new homeland, Schumacher, a trained economist, worked alongside the renowned John Maynard Keynes. Together they reordered the global economy, creating institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, and sparking rapid postwar recovery. In factories, automation increased productivity, while agriculture saw higher yields thanks to the introduction of fertilisers and synthetic pesticides. Economies boomed, unemployment fell and wages rose.

Daily life was becoming more pleasant for everyone, but Schumacher felt a growing unease. Progress, he thought, was breaking the bond with ourselves, with each other, with nature, with the divine. He referred to industrial society as ‘the mother of the bomb’, as it had grown out of the same roots as the atomic bomb – ‘a violent attitude to God’s handiwork instead of a reverent one’. He concluded: this is all a great failure.

In lectures and essays from the 1960s onwards, Schumacher asked pressing questions. Is economic growth really such a good thing? Doesn’t it contribute to social disruption? How long can growth be sustained? Isn’t there more to life than money? Should technology keep advancing? Why should companies, profits, cities, the world population, everything, keep getting bigger and bigger?

Schumacher had answers, too. The worship of economic growth was wrong. Growth had ruined us. He used inverted commas for words like ‘modernisation’ and ‘development’ to illustrate his scepticism.

In one of his essays in Small Is Beautiful (1973), Schumacher addressed Snow directly. He deemed the optimism of scientists, which Snow said was needed to solve problems, as ‘guilt-ridden’ because of the damage their inventions had caused. No scientific or technological advance, nor any political or economic reform, could solve ‘the life-and-death-problems of industrial society’, he said, because the problems ‘lie too deep, in the heart and soul of every one of us. It is there that the main work of reform has to be done – secretly, unobtrusively.’

Luckily, Schumacher knew the right course. In 1955, he found inspiration in Burma, now Myanmar. He was there for three months to give economic advice, an important part of his role during the 20 years he worked as a top adviser to the British nationalised coal industry. As a representative of one of the world’s largest organisations, he defended the interests of coal against the rapid rise of oil and nuclear power – new, competing energy sources, about which he aimed to curb the apparent ‘limitless optimism’.

In Burma, Schumacher visited several villages before concluding that the locals needed little advice. Indeed, Western economists could learn something from them. ‘They have a perfectly good economic system which has supported a highly developed religion and culture.’ (2) He retreated to a Zen monastery and sat down to reflect. Here, he formulated the principles of a ‘Buddhist economy’, in which not greed but ethics, harmony and personal development were central (3). Schumacher felt he had found an ideal society. In reality, the people of Burma were plagued by ethnic violence and their life expectancy hovered around 40 years.

When Schumacher died in 1977, The Times declared ponderously: ‘To very few people is it given to begin to change the direction of human thought.’ The Times considered Schumacher to belong to this minority. ‘Small is beautiful’ was the motto that made him into a big name. It became the title of his 1973 book, which at the end of the 20th century was included in the Time Literary Supplement’s list of the 100 most influential books since the Second World War.

His plea for a smaller scale underpinned an intensifying call for setting limits to growth. We had to cut back: use less energy, buy less stuff, do away with our cars, have fewer children, close down industry. For those in Europe and the US with an interest in alternative living and holistic thinking, Schumacher became an inspiration. They shared his desire for a lifestyle less dominated by consumerism. They looked backwards to a mythical past, when nature was pure and morals unspoiled. They began to value tradition and longed for a connection with the local community. City dwellers began organising themselves into smaller groups – back to the village, back to nature. They grew food in their own organic gardens. They got their energy from ancient sources, such as wind and wood. As their own families grew smaller, they warned of population growth among those who weren’t like them. And they searched for meaning, contrasting puny humankind, which was to be distrusted, with grand nature, which was to be admired.

If these beliefs had once been recognised as conservative, now they also became applicable to those who maintained their beliefs were ‘progressive’.

Schumacher’s vision resonated with others. In the early 1970s, The Limits to Growth became the title of an influential report by the Club of Rome, a think-tank consisting mainly of captains of industry. Young, ambitious critics of modern society emerged on the scene. During a discussion on nuclear power, Paul R Ehrlich, a butterfly expert who wrote a bestseller on population growth in the human species, scolded: ‘Giving society cheap, abundant energy would be the equivalent of giving an idiot child a machine gun.’ (4) Criticism of mainstream thinking on energy prompted Amory Lovins, later the intellectual architect of Germany’s Energiewende (energy transition), to propose, as he put it in 1977, an alternative: ‘using as little energy’ as possible.

Nuclear power, developed at a time of discomfort with technology and contempt for science, became the embodiment of an unnecessarily complicated technology – one surrounded by danger and secrecy, and enclosed by barbed-wire fences and warning signs. Was this what progress looked like?, asked its many critics.

In a society seeking simplicity, there was little appreciation for boiling water by setting in motion a chain reaction of unstable atoms of enriched uranium. In people’s minds, a coal-fired power plant was just a scaled-up furnace, a wind turbine was simply a modern version of the old windmill in the barnyard, and a beaver could build a hydroelectric plant if it was somewhat stronger. But a nuclear plant? Were genius inventors like James Watt or Thomas Edison to travel to the future in a time machine, even they would have no clue what was going on in a nuclear reactor.

As soon as nuclear energy took off in the 1960s, warnings were issued, mainly from members of the environmental movement and the coal industry. Representing both groups, Schumacher labelled nuclear fission in Small Is Beautiful ‘an incredible, incomparable and unique hazard for human life’. He also described nuclear plants as ‘satanic mills’. In another chapter, Schumacher lamented on page after page that too many British coal mines were closed in the 1960s, ‘as if coal were nothing but one of innumerable marketable commodities, to be produced as long as it was profitable to do so and to be scrapped as soon as production ceased to be profitable’.

Safety concerns were also heard from some within the nuclear industry. George Weil had worked on reactor designs and wrote an exposé in 1971. Weil, who removed the control rods one by one in the world’s first nuclear reactor at the Chicago squash court in 1942, now deemed nuclear power to be dangerous and inefficient. Nuclear plants, he wrote, ‘offer too little in exchange for too many risks’ (5).

Concerned insiders reported incidents or near misses that could have had major environmental consequences but were hushed up by the authorities. They were not so sure exposure to radiation was without harm and they criticised the nuclear industry’s close relationship with the military.

Their candid reservations contrasted with the cocky attitude of the industry, which continued to boast of endless possibilities. For instance, the US Air Force squandered billions of dollars in fruitless attempts to use nuclear power in aircraft. There seemed to be no end to their future plans. Small atomic bombs must be detonated to dredge canals and a nuclear missile must be fired at the moon, just to see the effect.

Scepticism of nuclear miracles reached Hollywood. On 16 March 1979, The China Syndrome premiered in cinemas. Jane Fonda plays a television reporter, Michael Douglas a cameraman. They’re filming inside a nuclear plant when an incident occurs. Alarms go off. The floor is shaking. Panic in the control room. For a while, it looks like the place could explode. In the end, it fizzles out.

Then attempts to dismiss the incident as trivial begin. The energy company obstructs an investigation into the events. Superiors at the TV station refuse to broadcast the secretly recorded footage. An independent expert looks at the film and concludes that everyone for miles around is lucky to be alive. When a plant employee notices a leaking pump and discovers that a safety report has been falsified, he is ignored. Film critics raved. ‘A terrific thriller that incidentally raises the most unsettling questions about how safe nuclear power plants really are’, wrote one renowned reviewer. The New York Times stated that the film was ‘as topical as this morning’s weather report, as full of threat of hellfire as an old-fashioned Sunday sermon and as bright and shiny and new-looking as the fanciest science fiction film’. Critics were careful to mention that the fictional events were based on real mishaps, such as the stuck needle on a meter that caused technicians to misjudge the water level.

The nuclear industry bit back. The film was said to be full of fantasies, accusations and errors. An executive declared: ‘The systems are designed and built in such a way that a reactor will operate safely even if there is a significant equipment failure or human error.’

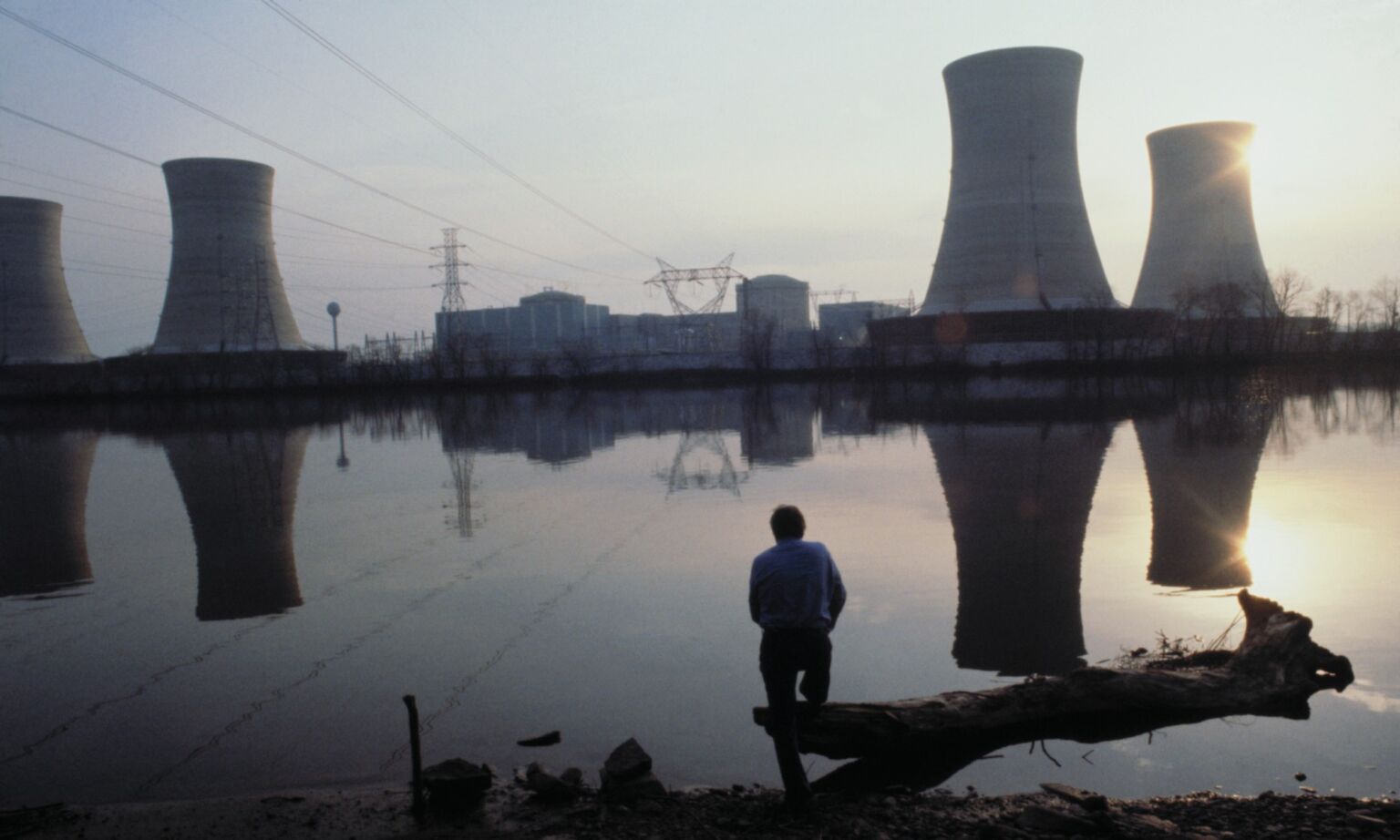

However, 12 days after The China Syndrome was released, alarms rang out in the newest reactor at Three Mile Island, a nuclear plant near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. A minor malfunction in the cooling system had caused the reactor to shut down automatically. In the control room, hundreds of lights started flashing but none revealed that a relief valve had failed to close, causing coolant to drain and the reactor core to heat. Because the operators could not see on their instruments that the valve had remained open, their decisions resulted in a partial meltdown. Radiation escaped.

The next day, authorities insisted there was no cause for concern. Local residents listened and thought, ‘yeah, right’. Some 140,000 chose to evacuate their homes for a while.

News about Three Mile Island reached Europe at a time when Germany was writing the next chapter in its protest against nuclear power. Resentment at the decision to store radioactive waste in a salt mine in Gorleben in Lower Saxony caused opponents to organise a multi-day march 100 miles long. It started with a few hundred hikers and cyclists. When the tour concluded in Hanover, newspapers were brimming with stories on what remains the most serious nuclear plant accident in the United States, leading to a turnout of at least 50,000 protesters in the German city.

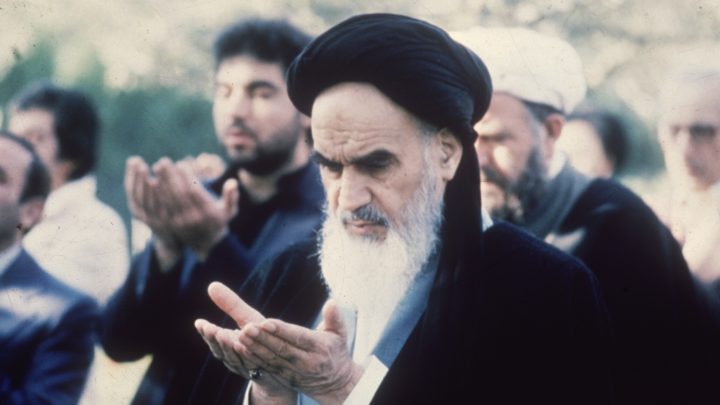

Opponents of nuclear power were winning. With 50.5 per cent of the vote in a referendum, Austrians prevented the commissioning of a fully completed nuclear plant at Zwentendorf an der Donau. The Swedes spoke out in their referendum against the construction of new nuclear plants in general. The Spanish declared a moratorium. One thing was clear: people did not want this. Nuclear power? No, thanks!

The industry crumbled. Construction plans for nuclear plants ended up in the shredder. After the Three Mile Island accident, pending orders for reactors came to a halt. Several nuclear plants under construction were converted into coal- fired facilities, without too much resistance from locals or environmentalists. A few nuclear plants that had already been built were mothballed before opening, such as the one on Long Island near New York City. After years left empty, the finished nuclear plant in Kalkar, Germany was being turned into a theme park complete with Ferris wheel and ball pit.

Due to their success, protesters developed a taste for more. Green parties were forming in Europe on a base of anti-nuclear activists. By the 1980s, they were making a breakthrough, with Die Grünen in Germany being a pioneer. These parties developed a comprehensive programme around nature protection and a cautious approach to technology. They broke with the style of traditional political parties, refusing to brand themselves as left or right, and found their electoral base mainly in ‘progressive’ university cities. Everywhere, Green parties became the natural home for people who really don’t like nuclear power.

Three years after carrying out a terrorist attack on a French nuclear plant, Chaïm Nissim entered politics in 1985 as a representative for Grüne Schweiz, Switzerland’s newly formed Green Party. By the time Nissim gave up his political work in 2001 and prepared to confess to the 1982 attack in L’amour et le Monstre (2004), his colleagues in Germany and Belgium were part of a coalition government. They seized the opportunity for a firm decision: all nuclear plants must close. The Belgian government went one step further and enshrined in its constitution that there should never be another nuclear plant.

By the turn of the 21st century, the dissenting voice had become the dominant one.

Marco Visscher is an author and journalist based in the Netherlands.

The above is an edited extract from Marco’s new book, The Power of Nuclear: The Rise, Fall and Return of Our Mightiest Energy Source, published by Bloomsbury. Order it here.

(1) The First Nuclear Era: The Life and Times of a Technological Fixes, by A Weinberg, Springer, 1974, p271

(2) ‘Schumacher in conversation with Satish Kumar, founder of the Schumacher College’, included in This I Believe and Other Essays, by EF Schumacher, Green Books, 1997, p8

(3) ‘Buddhist Economics’ first appeared in Asia: A Handbook, by G Wint (ed), Praeger, 1966; it is also included in Small Is Beautiful: A Study of Economics As If People Mattered, by EF Schumacher, Blond & Briggs, 1973, p38

(4) ‘Machine guns and idiot children’, by P Ehrlich, featured in Not Man Apart, Vol 5, no18, September 1975. The magazine was a publication of Friends of the Earth.

(5) ‘George Weil, from activator to activist’, New Scientist, 30 November 1972

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.