Long-read

Grooming gangs: the making of a scandal

How elite fears of social unrest and accusations of racism led the state to look away from industrial-scale abuse.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Thanks to the numerous local inquiries and court cases, this much we do know about the grooming-gangs scandal. From at least the 1990s and likely long before then, criminal networks prostituted, raped and tortured thousands of young girls in towns and cities across the UK. And the authorities, despite being aware of what was happening, did very little to intervene.

The sites of the abuse may differ – significant gangs have been identified and partially prosecuted in Bradford, Derby, Newcastle, Oxford, Telford, Rotherham, Oldham, Birmingham, Rochdale and many more places. But we know that the pattern of offending remains similar. Groups of men working in or around the nighttime economy target 11- or 12-year-old girls, often from challenging backgrounds. They pose as their ‘boyfriends’. They ply them with drink and drugs. Then over months and years they rape them. They pimp them out for sex with other men. They beat and threaten them.

These organised abusers have left a trail of human devastation across parts of the UK that we are still to come to terms with.

But we also know something else about grooming gangs: the perpetrators are mostly of Pakistani heritage, while the victims are overwhelmingly white. For our political and cultural elites, this has been treated as something to be squeamish about, ‘an awkwardly inescapable part of the story’, as one Guardian columnist put it.

Yet the ethnic identity of the perpetrators is not merely an ‘awkward part of the story’. Their ethnic identity is integral to the scandal itself. This is not, as racists are desperate to imply, because the horrendous actions of these particular men show how wicked and anti-white all Pakistani people are – cue despicable talk of mass deportations, etc. No, it’s because the predominant ethnic identity of the perpetrators is precisely what fuelled the state’s shameful, years-long reluctance to tackle the problem of grooming gangs in the first place.

This is what makes it such an epoch-defining scandal. Not just the violent, sexual exploitation of thousands of young girls, but also the authorities’ long-standing failure to stop it. Because, thanks to the ethnic identity of the perpetrator, they feared doing so would provoke accusations of racism. That it would stoke tensions in already racially divided towns. So they looked the other way. The abusers were emboldened, empowered even. And the victims were betrayed.

There is now little question that local constabularies, councils and other state agencies were aware of the horrific offences being committed right under their noses from at least the late 1990s onwards. Take Tom Crowther KC’s four-volume report into child sexual exploitation in Telford, Shropshire, which was published in 2022. Crowther notes that there was widespread awareness that gangs of largely Pakistani or ‘Asian’ men were systematically sexually abusing youngsters at least as far back as the 1990s. It was ‘commonly known among police officers, police civilian employees, and the public’, he writes.

What’s more, the police’s intelligence system had compiled copious reports on the gang-led sexual abuse of youngsters, but had failed to act on any of them. ‘At least between February 1997 and July 1999’, he writes, ‘no steps were taken to assess, investigate or disrupt what I consider to have been obvious patterns of organised and serious sexual offending against children’. The cost of Telford’s authorities’ negligence is staggering. In 2018, the Mirror reported that there could be as many as 1,000 victims of Telford’s grooming gangs. Surveying the evidence, Crowther conceded that number was ‘conservative, or in the words of one witness, “tame”’.

Then there’s Alexis Jay’s 2014 inquiry into child sexual exploitation in Rotherham, which looked at the period 1997 to 2013. Social workers told the inquiry that they had come across examples of what they called ‘child prostitution’ at the hands of groups of ‘Asian’ men from the early to mid 1990s onwards. Indeed, local youth workers had even responded to the problem of girls in local residential care units being targeted by criminal gangs by establishing a project called Risky Business. That was in 1997. Working with other agencies, Risky Business soon identified over 80 under-18s who were being prostituted. Yet those referrals, like so many future ones, seemingly went nowhere. As in Telford, the cost of such negligence is shocking. The Jay report put the number of grooming-gangs victims in Rotherham at over 1,400 – a figure Jay, like Crowther, felt was ‘a conservative estimate’.

Across the Pennines in Rochdale, it was a similar story. In a 2024 report on ‘non-recent child sexual exploitation’ in the town, it was revealed that councillor Sara Rowbotham – as part of an NHS sexual-health service known as the Crisis Intervention Team – had repeatedly told the police and children’s care services about the organised sexual exploitation of vulnerable youngsters in the mid-2000s. She told the inquiry her team had shared a wealth of information to suggest kids were being sexually exploited by an organised crime gang led by two professional criminals operating out of two takeaways. Again, those tasked with protecting these at-risk young people ‘failed to respond appropriately’.

Which is one way of putting it. While the care service was complacent and local councils wilfully downplayed the significance of the gangs, the police treated the gangs’ victims with active disdain. According to a 2002 Home Office report on tackling prostitution, young women in Rotherham complaining of sexual abuse were being ‘threatened with arrest for wasting police time’.

The countless individual stories of victims’ treatment are truly shocking. The Jay report tells of the experience of ‘Child A’ who was just 12 when, according to her case file, she began associating with ‘a group of older Asian men and possibly taking drugs’. She told the police that she had had sex with five adults, two of whom were given cautions. But the police refused to see this for the sexual abuse it clearly was. In the absurd words of one senior detective, the child had been ‘100 per cent consensual [sic] in every incident’.

Then there’s the case of a then 12-year-old girl referred to as ‘Child H’. She told her care workers that she and another child had been sexually assaulted by a gang of men. She was later found drunk in the back of a car with a man who had indecent photos of her on his phone. Yet just three months later, her care worker concluded she was not at risk of sexual exploitation. A few weeks later, the police found her and another child in a derelict house with a group of men. She was arrested for being drunk and disorderly, while the men were let go without charge.

Then there was the tragic case of Rochdale teenager Victoria Agoglia. In 1998, she was put into care by her mother when she was eight years old. After her mother’s death, she soon found herself being regularly moved between foster homes. Her chaotic life, including countless episodes of going missing, left her vulnerable to the local predators. They soon pulled her into their world, plying her with drugs and raping and abusing her. Aged 13 she scribbled a self-loathing note detailing all the illicit substances she was taking and admitting having ‘slept with people older than me, half of them I don’t even know their names – I am a slag and that is nothing to be proud of’. Local care workers were aware of what was happening to her and deemed her ‘at risk’ – as were the police after she required medical attention following a sexual assault. Yet all those in a position to help her failed to do so.

In 2003, the then 15-year-old Agoglia was going regularly missing from her care home, sometimes for weeks at a time. The police were asked to look for her, but made little effort to do so. It turned out that she was being taken away to be sexually abused by large groups of men in return for drugs and cash. In September 2003, Victoria was sent to the home of 50-year-old Mohammed Yaqoob, who injected her with a large dose of heroin. She died in hospital five days later. Yaqoob was sentenced to just three and a half years in jail – for the single charge of injecting her with a noxious substance.

A 2019 review into the conduct of Greater Manchester Police provided a sober but damning portrait of Agoglia’s care: ‘Her exposure to sexual exploitation by adult males was known to police and social services and, despite the risk of significant harm caused by the men who were sexually exploiting her, statutory child-protection procedures, which should have been deployed to protect her, were not utilised.’

These individual tragedies were not aberrations. They were the norm. As report after report has shown, the authorities were all too aware of the violent abuse and rape of children by criminal networks in towns and cities across the UK. And time and again they failed in their duty of care. The words of a serious case review on the police response to an Oxford grooming gang could apply to local social services and forces across the country: ‘[They] failed to see that these children were being groomed in an organised way by groups of men.’

Part of the reason lies in the authorities’ dim view of the victims. From dysfunctional families, and often in and out of care homes, these young girls were seen as lost causes before their lives had really had a chance to begin. Their chaotic behaviour, from truanting to pre-teen alcohol and drug use, elicited contempt rather than sympathy from the authorities. They were seen as ‘deviant’ and ‘promiscuous’. As one care worker told the Jay inquiry, ‘the attitude of the police at that time seemed to be that they were all “undesirables”… young women [who] were not worthy of police protection’.

This kind of class prejudice certainly made the grooming-gangs scandal possible. It enabled the authorities to dismiss the victimisation of hundreds upon hundreds of children, casting them as part of a feckless underclass. In this, they politely echoed the vicious, racialised disdain of the abusers themselves, who, as court cases have revealed, viewed their prey as ‘white slags’ and ‘whores’.

But if class prejudice provided the conditions for a lack of state action, it was the racial identity of the perpetrators that all but ensured nothing would be done. It was the very fact that these networked child abusers were from ethnic-minority backgrounds that fuelled the authorities’ willful inertia. The ethnicity of the perpetrators impelled state bodies, from the care service to the police, not to intervene.

The background is important here. At the very moment local authorities were being made aware of ‘Asian’ men allegedly abusing vulnerable youngsters in the mid-to-late 1990s, the British state was busy diagnosing itself with ‘institutional racism’. This was the explicit charge levelled at the Metropolitan Police in 1999 in the Macpherson Report, following its deeply flawed and prejudiced investigation into the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence by a white, racist gang.

This partially explains why local bodies were so concerned that intervening could lead to charges of racism. In her report into the Rotherham grooming gangs, Jay notes that in the ‘early years’ of the scandal, several council staff ‘described their nervousness about identifying the ethnic origins of perpetrators for fear of being thought racist’, while ‘others remembered clear direction from their managers not to do so’. This ‘nervousness’ about addressing the nature of the abuse led some councillors to simply ignore the issue entirely. They ‘seemed to think it was a one-off problem, which they hoped would go away’.

In his inquiry into the Telford grooming gangs, Crowther found that the police in particular were worried about charges of racism. ‘In the 1990s and early 2000s and even beyond’, he writes, ‘a concern about racism, and being seen to be racist, permeated the mind of West Mercia Police’. This led to ‘a reluctance to police parts of Wellington’ (a town in Telford borough). One witness told the inquiry that on being approached to join a team tasked with investigating allegations of abuse, they refused to do so: ‘I said no, and that was because of the Asian element, you know, we’re going to be on to a loser.’ It was the same story in Rochdale. A senior investigating officer, in trying to explain why the police were not stopping the countless Asian taxi drivers seen ferrying around single young girls, ‘I can only guess that Greater Manchester Police patrols were frightened of being tarnished with a race brush for doing it’.

Such fears were reinforced by what happened to those who did speak out publicly. When in 2003, Ann Cryer, the then Labour MP for Keighley in West Yorkshire, told a TV interview about several 12- and 13-year-old girls being sexually exploited by a group of older Asian men, she was roundly attacked as a racist.

But it wasn’t just fear of being accused of racism that fuelled institutions’ active reluctance to intervene. It went deeper than that. They were fearful, above all, of social disorder.

Years of multicultural policymaking had helped fuel division and segregation in certain towns and cities. It had fostered a sense of grievance and victimhood among members of different, increasingly antagonistic communities. Mutual distrust reigned between them as they lived separate, ‘parallel lives’ – a phrase used by Ted Cantle in his 2001 government-commissioned review into social cohesion. As a result, the authorities had become preoccupied with policing intercommunal tensions, especially after the race riots in Oldham, Burnley and Bradford in 2001. They were therefore terrified of how the public would react to the facts of the child sexual exploitation scandal then unfolding, especially in the very towns that only just erupted in violent unrest. They feared the reaction of Asian communities to a targeted clampdown on British Pakistani criminal gangs. Above all, they feared the reaction of Britain’s white working class, which they saw as a racist mass just waiting to erupt. It was a view that insults all communities and sections of society.

Every single one of the reports into the local grooming-gangs scandal is shot through with this same elite anxiety over social disorder and unrest. In Oldham in the early 2010s, an official safeguarding document warned that ‘the proactive confirmation of ethnicity [in the grooming gangs] could provide ammunition for far-right groups’. In Rotherham, a senior police officer warned the father of an abused teen that the town ‘would erupt’ if the routine abuse of children by Pakistani men became public knowledge. Jay’s report talks of the broad ‘concern’ among the local authorities ‘that the ethnic element could damage community cohesion’. As a former senior police officer told Louise Casey’s 2015 report on Rotherham council: ‘They didn’t want riots.’ Likewise, Crowther speculates that West Mercia Police’s abject failure to intervene in Telford stemmed from a fear of stoking ‘racial tensions’.

Birmingham City Council was so concerned about social disorder that it even buried its own report from the early 2000s on links between child sexual exploitation and Asian taxi drivers. Later, in 2015, the Birmingham Mail forced a 2010 West Midlands Police report on grooming gangs into the light using freedom-of-information requests. In it, the police warned that ‘the predominant offender profile of Pakistani Muslim males… combined with the predominant victim profile of white females has the potential to cause significant community tensions’. And so they withheld the report from public view for five years.

We were given an early glimpse of how this elite fear of disorder was driving the reluctance to face the problem of grooming gangs head on in 2004. In May of that year, on the eve of local and European Parliament elections, Channel 4 was due to broadcast Edge of the City, a documentary about social workers operating in the most deprived parts of Bradford. In one section, two white mothers from the nearby town of Keighley allege that their young teenage daughters have been groomed and sexually abused by individuals from the local Asian community. Social workers warned Anna Hall, the director, that the issue was too ‘racially sensitive’ to feature. But Hall kept it in, noting that the issue of child sexual exploitation at the hands of groups of men ‘kept surfacing’ during filming. In the run-up to its broadcast, the BNP advertised it on its website as ‘a party political broadcast’. This prompted the chief constable of West Yorkshire Police to join left-wing activists in calling for Channel 4 to cancel the screening. Just hours before Edge of the City was due to be broadcast, Channel 4 complied with police advice and pulled it from the schedules.

In a further twist, a 2019 review into sexual exploitation in Manchester claims that Greater Manchester Police launched Operation Augusta, its investigative response to the death of Victoria Agoglia, partially because it feared the public reaction to Edge of the City. The suggestion being that the similarities between Agoglia’s case and those covered in the documentary would stir up unrest. That Operation Augusta was promptly shut down the following year, despite not having completed its investigations, suggests that its ultimate purpose was to manage the public rather than tackle grooming gangs.

Edge of the City was eventually broadcast several months later. Still, in many ways, the affair captures the key dynamic of what we now know of as the grooming-gangs scandal; namely the refusal of the authorities to confront groups of largely Pakistani-heritage men committing the most abject crimes because doing so could inflame social tensions. In their eyes, it could anger Asian communities and it could drive a white working class into the arms of whatever wretched far-right group is the monster du jour.

Over the past decade or so, the horrific actions of these gangs of morally unconscionable men have been slowly exposed. Brave journalists, from Julie Bindel to Andrew Norfolk to Charlie Peters, have lifted the veil on the extent and nature of systematic rape and torture of vulnerable kids. Successive court cases have revealed the depths of these gangs’ depravity. And countless individual, localised inquiries have provided a sense of the potential scale of the rape and abuse.

Yet there still are too many among the authorities and our broader political and cultural elites who remain wedded to the tragically flawed thinking that fuelled this social catastrophe in the first place. They continue to warn, as Labour health secretary Wes Streeting did last week, that ‘inflammatory rhetoric’ around grooming gangs could lead to social unrest and far-right violence. They still flirt with labelling those focussing on the organised abuse of young girls as racist. And they willfully downplay and dismiss the scale and significance of what has happened, invariably using and abusing crime statistics on child sexual abuse.

The political class’s deflections and equivocations of the past few weeks show we still need a true reckoning with the driving forces behind the grooming-gangs scandal. A reckoning, above all, with the elite fear of disorder and unrest which led to countless state bodies to elevate some notion of ‘social cohesion’ above upholding the law.

As Tom Crowther wrote in his 2022 report on abuse in Telford: ‘It is impossible not to wonder how different the lives of those early 2000s victims of [child sexual exploitation] – and indeed many others unknown to this inquiry – may have been, had [the police] done their most basic job and acted upon these reports of crime. It is also impossible, in my view, not to conclude that there was a real chance that unnecessary suffering and even deaths of children may have been avoided.’

These words should send a chill down the spine of all those continuing to make the same mistake today. There is no excuse for looking the other way.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

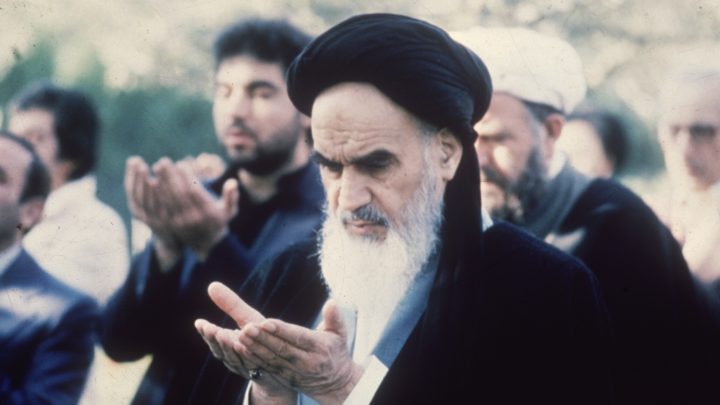

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.