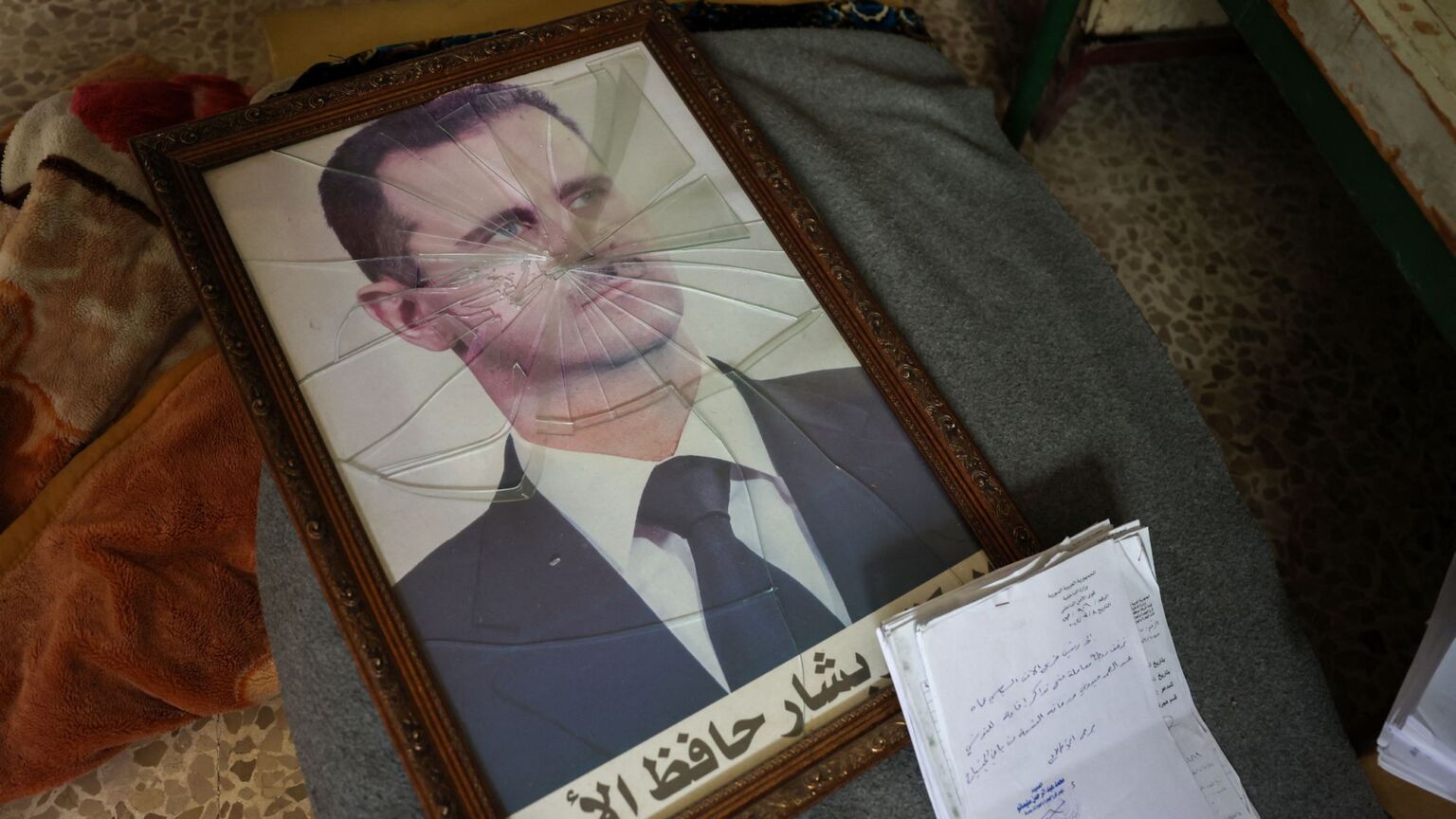

How Assad’s Potemkin dictatorship crumbled

His rotten, brutal reign is over. What now for Syria?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

And just like that, Bashar al-Assad’s reign over Syria is no more. Over the course of a mere two weeks, what looked from the outside like a brutal but relatively stable regime has evaporated into thin air.

When several thousand opposition fighters, headed up by Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), launched their offensive in late November, few would have predicted their triumph. Riding out from their anti-Assad hold-outs in Syria’s north-west, in pick-up trucks and on motorbikes, they looked like what they were – a fearsome set of militias, but surely no match for a state army backed by Russian airpower.

The HTS-led forces soon took towns and villages with ease. By last weekend, they had captured Syria’s second city, Aleppo, and were seemingly advancing on the capital, Damascus. Even then, few inside and outside Syria believed that Moscow-backed government forces would not at some stage mount a counter-offensive. On Saturday, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov insisted that Russia ‘was trying to do everything possible to prevent terrorists from prevailing’. Rumours circulating that Assad had fled were denied. The interior ministry announced that the army was forming a ‘ring of steel’ around the capital. Surely, there would be a fightback.

But the fightback never came. The insurgents were able to enter and capture Damascus without really having to lift a weapon – except to fire celebratory shots into the sky. By Sunday, HTS had announced that ‘the city of Damascus is free from the tyrant Bashar al-Assad’, and a few hours later HTS leader Abu Muhammad al-Jolani, now going by his original name Ahmed al-Sharaa, was declaring victory in a speech to the nation from within Damascus’ historic Umayyad mosque, the same mosque at which Assad would usually mark Eid.

The speed with which Assad’s rule has collapsed and the sheer absence of any resistance reveals a stark truth about Syria’s fallen dictatorship. It has been completely hollowed out over the past decade or more of conflict. This was a regime built on repressive force that now lacked any actual force. A regime whose authority rested on military strength that now lacked a strong military. And so when Islamist factions pushed at the doors to the palace, as they did both literally and figuratively this weekend, they simply opened.

Few will mourn the passing of the Assad family’s half-century-long exercise in despotism. Bashar’s father, former airforce pilot Hafez al-Assad, had been a key player in a military coup in 1963, which brought the Ba’ath Party to power. When Hafez became president in 1971, it wasn’t due to popular support. From the start, his regime’s authority rested almost entirely on its use of force, principally through Syria’s much feared intelligence and security agencies.

Bashar al-Assad inherited this repressive regime, complete with its brutal security apparatus, in 2001. Initially feted by the West, this British-educated ophthalmologist set about liberalising Syria’s economy, largely for his and his network’s own benefit. At the same time, he busied himself repressing any hints of dissent and striking up a close relationship with Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in neighbouring Lebanon – all the better to suppress their mutual opponents.

It was the popular uprisings in 2011, and the subsequent conflict between internationally backed factions within Syria, that marked the beginning of the end for the Assad family’s miserable, decades-long tyranny. Assad effectively lost control from that moment on. The Kurds were fighting for autonomy in the east, Turkish-backed militias were battling for control in the northern borderlands and myriad Islamist militias were flourishing in the surrounding chaos. It took the harsh military intervention of Russia, Iran and Hezbollah from the mid-2010s onwards for Assad to regain a semblance of power.

But it really was just a semblance. Although order did appear to have been restored in 2018 after Russia shelled the last of Assad’s opponents, then holding out in Daraa, into submission, his regime was now reliant on external actors for survival. There was still a national army, of course, but amid the broader economic devastation of Syria, its rank and file were underpaid and demoralised while a self-interested officer corps concentrated on enriching themselves. The Syrian state had effectively become little more than a decadent ruling clique propped up by the military force of Russia, Iran and Hezbollah – each intent on using Syria for their own strategic interests.

The precarious balance of forces within Syria could only last for as long as Assad’s regional and global backers were able to sustain it. The moment they were not, Assad was in trouble. That moment arrived in two phases. First, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, and second, with Iran and Hezbollah’s latest clash with Israel, after Hamas’s attack on Israel on 7 October last year. As they refocussed their military resources away from Syria, they pulled the rug out from under Assad’s rotten kleptocracy. It left a Potemkin dictatorship, whose authoritarian facade hid the internal decay and collapse of Assad’s power.

And so, as the HTS-led factions approached first Aleppo, then Homs and eventually Damascus, the Syrian army’s soldiers melted away. Some have reportedly fled to Iraq. Others just returned to their homes. As Danny Mekki, a Syrian journalist in Damascus noted, ‘the regime was just running away’.

Many Syrians are elated at the fall of Assad. They suffered immensely under his and his family’s despotic rule. Over the past decade, his foreign-powered regime laid waste to towns and cities. He and his father were responsible for torturing and disappearing thousands upon thousands of people. And those who survived were plunged into Syria’s infamous prisons, the true, sadistic horror of which is only now emerging as militias free their inmates. Assad’s departure this weekend – to live in exile in Moscow – is the source of much understandable joy.

But it is joy fringed with caution. Syrians know of their liberators’ violent Islamist backgrounds, and especially of HTS’s brutal repressive rule, as the ‘Syrian Salvation Government’ in Idlib. And many will be all too aware of the factional conflicts that are already reigniting across Syria’s fractured territory.

Yet while Syria’s future remains deeply uncertain, one thing is clear: Assad will not be missed.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.