Long-read

The myth of the population time bomb

Why ageing and declining populations are not all doom and gloom.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

In Britain and most other countries today, the birth rate has fallen below replacement levels – usually defined as 2.1 babies per woman. Fertility first fell below replacement levels in about 1973, and since 2010 has fallen steadily to about 1.55 babies per woman. In a few countries, including China and Japan, there have already been absolute population declines.

These trends are now prompting a lot of doom-laden commentary from demographers, economists and politicians. They claim that an ageing population, with ever-fewer working-age people supporting ever-more retirees, is creating an unsustainable burden for society.

But these fears about an ageing population are not as new as they seem. In fact, in 1939, during a House of Lords debate on ‘population problems’, Viscount Samuel expressed concerns about Britain’s falling birth rate that are very similar to those being expressed today. ‘From the economic point of view’, he said, ‘it is obvious that a decline of population must mean a great diminution of productive power’. The economy will fall ‘into a period of decline’, he continued, which will have a terrible effect ‘upon our national finances owing to the burden of pensions for an older population’. He ended by pointing out that the growing debt ‘could hardly be borne by a greatly diminished population’. Fellow peer Viscount Dawson agreed. Counselling against complacency, he argued that ‘we have to bring home to people’ that the problems of an ageing population are ‘absolutely inescapable, inexorable facts passing into the next 20 years’, which are already ‘on top of us at the present moment’.

So concerned was parliament by the prospect of an ageing, declining population that, in 1944, it established a royal commission on population. By the time it published its findings five years later, it was still signalling that the demographic trends flowing from falling fertility could make society ‘dangerously unprogressive’.

We’re all well aware of what happened next: the postwar baby boom. By the end of the 1940s, fertility rates had already returned back above replacement levels. Britain’s population has since grown from 48million in 1939 to over 68million today.

Politicians, academics and other intellectuals in the 1930s and 1940s were right that fertility was low and the population ageing. But they were too eager to read a grim future into these real trends. Their fears were then disproved by the wealthier society that ensued, despite the population continuing to age.

There are obviously huge political, economic and cultural differences between then and now. But what this episode shows is that there are historical precedents for today’s population anxieties. They teach us, at the very least, to remain sceptical about demographic fear-mongering.

Then, as now, politicians, economists and other intellectuals downplayed or ignored the human benefits made possible by a steady growth in productivity. And then, as now, they erroneously presumed that low fertility and population ageing would itself be bad for productivity and economic growth.

Population ageing itself is not a new phenomenon, especially in developed countries which, over the past two centuries, have already experienced the demographic transition from high fertility / high mortality to low fertility / low mortality (1). This means that, at first, the average age of the population increased in these countries due to fewer people dying prematurely – especially infants and children. Then, declining fertility slowly took centre stage as the main driver for ageing. This phenomenon is known as ageing ‘from below’, with younger cohorts being smaller than their predecessors, which pushes up the population’s average age.

We’ve certainly seen this in Britain. First, reductions in elderly mortality raised the average age of the population. Then, in recent decades, the decline in fertility rates since the end of the baby boom has become the main driver behind the ascending age structure.

Yet these demographic trends did not create an unsustainable burden for society. That’s because, up until the 1970s, the steady growth in output per worker – ie, productivity growth – ensured that society was able to ‘afford’ a continuously ageing population, including the additional outlays for more elderly people. Indeed, during the 20th century, productivity growth in Britain was sufficient to improve material living standards five-fold.

Today, however, those concerned about ageing appear not to see this history. Instead, they warn about the economic and social consequences of an ageing and shrinking population. And they do so on a global scale. The Telegraph has warned that ‘the world’s falling birthrate is leading to economic catastrophe’. Economist Andrew Scott has suggested that falling fertility rates ‘represent no less than an existential crisis for humanity’. And demographer Paul Morland has claimed that smaller populations mean ‘the entire economic system will creak and perhaps collapse as those too old to work grow in number while those of working age shrink’.

Morland, in particular, worries that ‘population collapse is the greatest problem facing humanity’. In his cheerfully titled book, No One Left, he writes that we’re ‘running out of babies’.

These are not sober, reasoned analyses of economic and demographic data. They are pieces of excitable mythmaking, fuelled by misconceptions about the economic impact of population change. There are three main myths that are particularly misleading.

The first is that falling fertility is bad for economic growth and for living standards. It’s claimed that fewer people means fewer workers, which means less economic output. But anticipating arithmetical changes to the level of economic output does not imply anything about the rate of economic growth. That’s because the latter is a function of the rate of productivity growth, the average output of each of these workers. The size of a workforce therefore tells us nothing about the pace of growth being slower, or faster or flat.

Moreover, a smaller national output does not necessarily result in lower living standards – a product of GDP per capita, or national output divided by the total population. Take the latest Office for National Statistics (ONS) population projections for Britain, based on a long-term fertility-rate assumption of 1.59. Even in the implausibly dismal scenario of no productivity growth and no changes in employment rates for the rest of this century, the average GDP per capita of £33,257 today is projected to decline to about £30,500 by 2100. This is not a future anyone – degrowth environmentalists aside – would look forward to. But a gradual eight per cent fall in income over nearly 80 years – an average annual drop of 0.1 per cent – is hardly the ‘economic collapse’ portrayed by the population alarmists. And it can be overcome.

Indeed, a return to any decent productivity growth would overwhelm the arithmetical effect of population decline. With other assumptions staying the same, a productivity growth rate of just one per cent a year would see GDP per head double to over £65,000. With a return to the long-run productivity growth of two per cent, GDP per head would grow four-fold to about £140,000. Thus, even slightly raising productivity growth would swamp any income effects of the birth rate staying well below replacement levels.

The second myth is that we’re running out of people. For a start, it takes decades for below-replacement fertility rates to translate into a smaller population. So although Britain has had below-replacement fertility rates for half a century, the population is in fact still growing. And that is not all down to net migration. ‘Natural’ population growth – the annual balance of births and deaths – remains positive in Britain. According to the ONS, that is expected to continue for another couple of years.

In fact, if we extrapolate official sub-replacement fertility forecasts of about 1.6 per mother forever, and assume continually falling net-migration levels, the latest UN projections show Britain’s population continuing to grow for another half-century. It is expected to peak in 2073 at about 76million, with the subsequent decline being very gradual.

By 2100, with the population dipping 1.6 million from this 2073 peak, there are still expected to be more people in Britain than at any time before 2043. That does not amount to a dangerous shortage of people.

Other demographers worried about low fertility have helpfully extrapolated the UN’s global projections based on a fall to a global average of 1.66 babies per woman – the same as the US fertility rate in 2022. Their model shows that by the beginning of the 23rd century, there would still be over six billion people, the same level as at the beginning of the millennium. Recall that in 2000 most observers of population trends were worrying about there being too many people, not too few.

In short, gradually reversing the population increases of the 21st century over the course of the 22nd century hardly merits the term ‘disaster’. As for the threat of absolute depopulation, that would follow in about 12 centuries from now with no people left by about the year 3255. Put it in your diary.

Such demographic fear-mongering is an example of the fallacy of spreadsheet extrapolation. Historically, as evidenced in the mid-20th century, birth rates have fluctuated. They are not the result of statistical forces beyond our control. No, they are the result of human choices and actions. We don’t know the future, but who would bet against a fair few population-impacting changes over the next millennium? To imagine that the contemporary influences curbing birth rates will remain fixed over future centuries seems rather far-fetched.

The third and final myth we need to dispel is that favourite metric of anxious demographers. Namely, the old-age dependency ratio. This measures the number of people of retirement age compared to the number of working-age people. The direction of change of this ratio is not in dispute. While five British people of working age were supposedly supporting each elderly person back in 1970, today just three of working age are supporting each elderly person. This could well decline to just two for every one elderly person within the next half-century.

These figures are credible. It’s the dismal interpretation that is flawed. It is a mistake to see a person’s economic capability and role as determined primarily by their chronological age, rather than by what they do. Are they working or not? If they are, how productive is their work? If they are not in work, are they living off their own resources, or are they reliant on state welfare?

In reality, not all those of working age are independent, and not all those past working age are dependent. Consider who is most dependent here: a 70-year-old taking her full state pension of about £11,500, or a 35-year-old public-sector worker earning the median salary of £36,000. Both are paid from the same tax revenues, yet the public-sector worker is three times more ‘dependent’ on the country’s wealth producers than the pensioner.

In short, population alarmists are guilty of conflating numbers of working-age people with numbers of workers. Indeed, increasing numbers of people aged over 64 are working, and many others say they would like to work if they could find suitable jobs.

Many non-workers, including people older than 64, are physically and financially independent. They may also be doing socially valuable charity work or engaged in informal caring activities. And while the vast majority of the elderly are in receipt of a state pension, many rely primarily on their own accumulated asset wealth in property or savings in order to support themselves.

Furthermore, the focus of demographers on age-related dependency ignores one key fact. In Britain today, there are 12.3million children and 10.5million working-age adults not in work. By contrast, there are just 11million people aged over 64 not in work. This means there are twice as many people aged 64 and under not in employment than there are over it.

Finally, those obsessed with age-related dependency make an often ignored, but highly consequential, error. That is, young and old, working and jobless, ultimately rely for their incomes on produced wealth. In that sense we are all dependent on production, on the productive, wealth-making parts of the economy.

For these and more reasons, age-dependency ratios are hugely flawed as economic signifiers. What really matters in funding the costs of dependent people is not an arithmetical relationship between age groups, but the numbers of the people actually working. And factoring in any growth in worker productivity over time would, of course, make an ageing, diminishing population even more ‘manageable’.

Today’s demographic doomerism is not based on economics, let alone genuine concerns about the future. It is better understood as an expression of the fatalism and pessimism that now grips the imagination of our elites. In this, they share much with their predecessors in the 1930s. Against the background of an economic slump, political disarray and geopolitical tension, they too turned their fears and anxieties into demographic projections – projections that were confounded by the population growth and economic development of the 20th century.

We need to move beyond this fixation on population. It generates anxiety, leads to fatalism and sets old against young. It can also further deter people from bringing babies into what appears as an ever-more dangerous, uncertain and even apocalyptic world. By focusing instead on economic growth, on raising productivity and improving the quality of jobs people do, we can defuse the very idea of a demographic time bomb.

Perhaps then we might be in a position to create the additional wealth that Britain, and all countries, need to boost living standards, support genuine dependents – old and young – and build on the foundations of a civilised society.

Phil Mullan’s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Amazon (UK)

(1) See Chapter 2, The Imaginary Time Bomb: Why an Ageing Population is Not a Social Problem, by Phil Mullan, IB Tauris, 2000

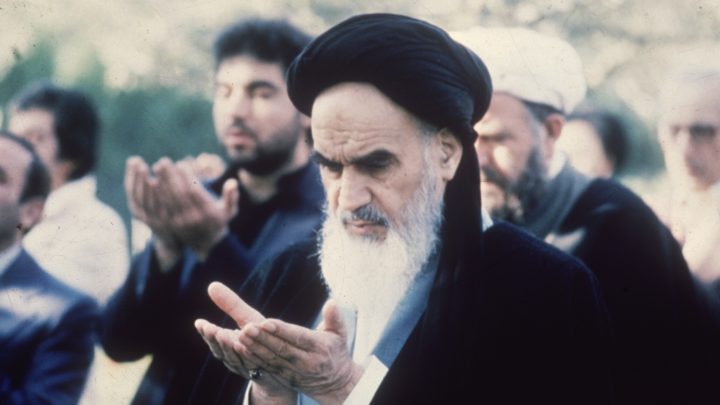

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.