We’re sending far too many people to university

Plans to push 70 per cent of young people into higher education would be a disaster.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

There is a plan afoot to turn British universities into little more than an extension of school. That at least seems to be the objective of Universities UK (UUK), a body that represents vice-chancellors.

In its ‘blueprint for change’, published this week, UUK states that the government should aim for 70 per cent of all young people to continue their education at university after leaving school by 2040. This would mean that nearly every school leaver would become a university student – and that university would, in effect, become a natural extension of the school system.

In many ways, UUK’s ‘blueprint’ continues the programme of widening access to higher education introduced by Labour prime minister Tony Blair 25 years ago. At the time, Blair announced that he wanted at least 50 per cent of young people under 30 to participate in higher education. Getting more bums on the seats of lecture halls proved relatively easy and New Labour’s target was met in 2019.

The programme of widening access was and continues to be justified on the basis of inclusion. However, the pursuit of inclusion has proved to be a fool’s errand. Yes, more people have been included in higher education since the late 1990s, but in the process the academic experience has been devalued. What students have been included in bears only a superficial resemblance to what a real university looked like just three or four decades ago.

The project of inclusion, of widening access, required the lowering of entry requirements. So as a growing cohort of new undergraduates piled into universities from the 1990s onwards, lecturers’ expectations of students steadily declined. As someone who worked as a university teacher from the early 1970s until very recently, I was shocked by how little was increasingly expected of undergraduates. Many in the humanities and the social sciences were no longer required to even read a book from cover to cover.

The lowering of expectations and standards inevitably ran in parallel with grade inflation. Soon the number of students graduating with a first began to rise. By the end of the first 2000s, even the most mediocre and slothful of undergraduates felt insulted if he did not at least gain a 2.1. The student who failed to pass an exam was fast becoming an endangered species. Indeed, in many universities exams were eliminated to relieve students of ‘unnecessary pressure’.

The fall in standards at universities was not lost on students’ prospective employers. Many became sceptical about the qualifications of graduates.

The expansion of higher education meant that universities soon started to resemble a school environment. The bored school kid soon reappeared as a bored university undergraduate. Many attended not because they had a passion for gaining new knowledge, but because they simply wanted to gain a paper qualification. In some cases, they were entirely turned off by discussions in seminars.

The presence of a growing proportion of uninterested students had an inhibiting effect on others. Students who were genuinely interested in their course and wanted to participate in seminars had to contend with what was fast becoming an unstimulating environment.

Many of my colleagues soon realised that they were expected to teach students who were not interested in their subjects at all. In my own field of sociology, I estimate that about a third of the students I was teaching in recent decades had little real interest in the course.

As a result of the Blair-era project of inclusion, thousands of students ended up wasting their time. Some of these students dropped out while others walked away with a paper degree. They would have been far better off if they had gone for an apprenticeship or joined the world of work.

If the UUK’s ‘blueprint for change’ is implemented, it would turn this already bad academic situation into a disaster. This would be terrible news for society as a whole. After all, we need our young people to acquire the real skills that are needed if Britain is to develop industrially and technologically. The last thing society can afford is more bored, time-serving undergraduates.

Not that any of this would bother UUK. The principal driver behind its ‘blueprint’ is the need for new funding schemes for a financially broken university system. But vice-chancellors’ desire for cash should be resisted. Taxpayers’ money would be far better spent on creating a world-class system of apprenticeships, rather than on subsidising mediocrity and failure.

Frank Furedi is the executive director of the think-tank, MCC Brussels.

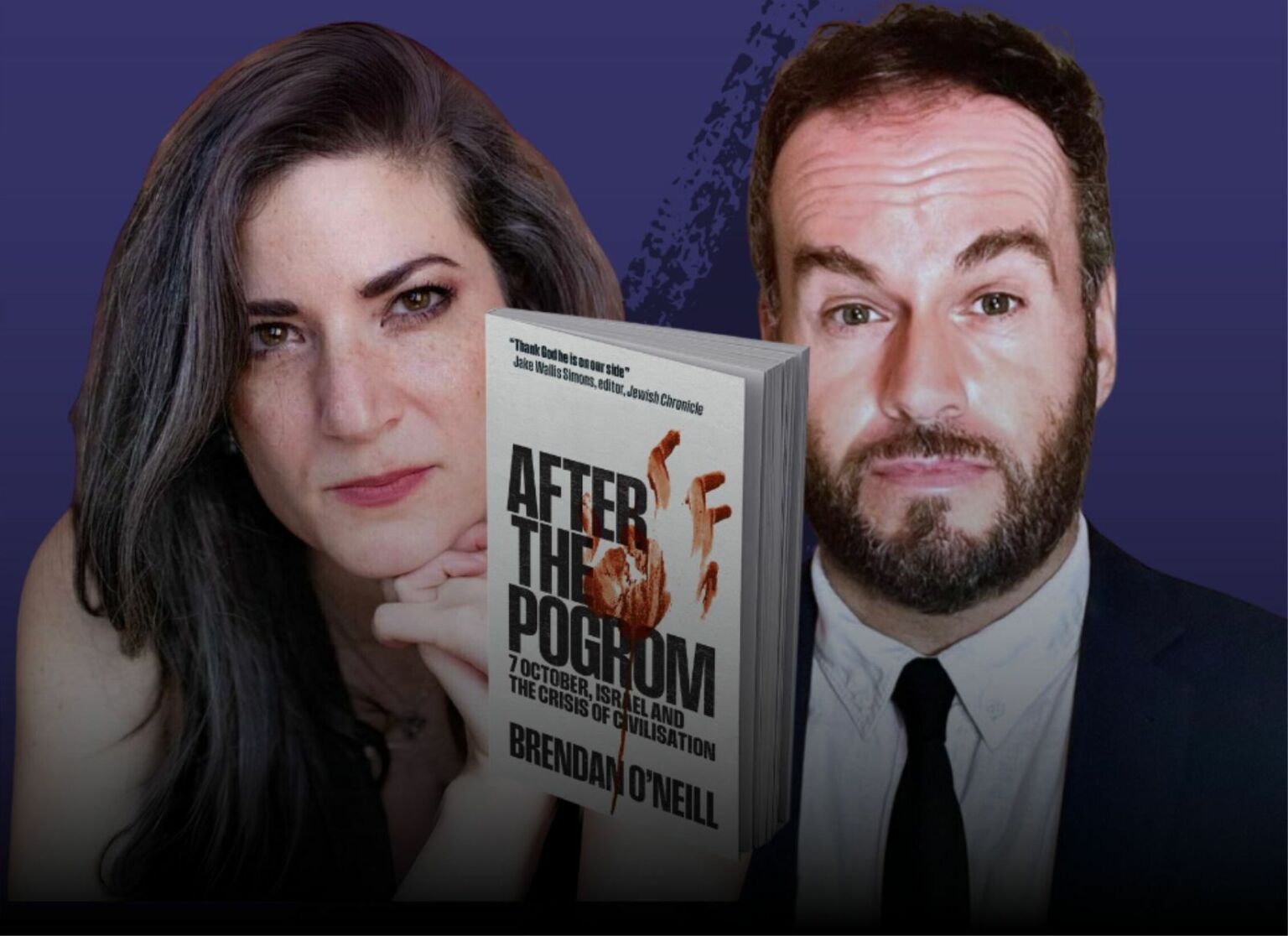

After the Pogrom – book launch

Tuesday 1 October – 7pm to 8pm BST

Batya Ungar-Sargon interviews Brendan O’Neill about his new book. Free for spiked supporters.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.