‘Workers of all races have a common bond’

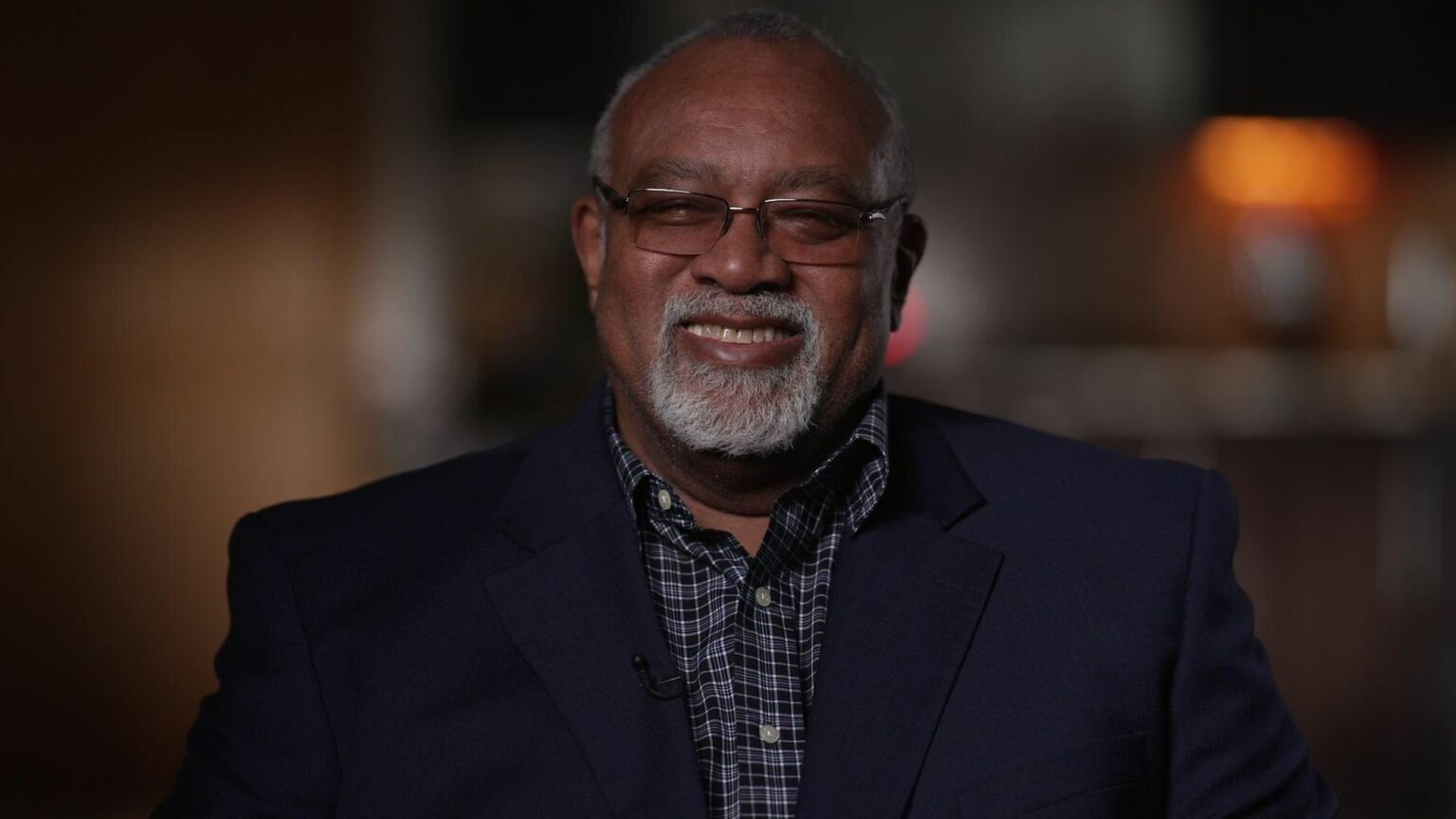

Glenn Loury on how obsessing over race corrodes working-class solidarity.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Glenn Loury is hardly your typical conservative. He has been, at various times, a high-school dropout and Harvard professor, drug addict and intellectual powerhouse. This unorthodox life birthed an equally unorthodox thinker. In his new memoir, Late Admissions: Confessions of a Black Conservative, Loury details how his experiences led him from left to right to left and back again, shaping him into a thinker unafraid to challenge consensus. He has been especially outspoken on matters of race, taking the left to task for its identitarian, patronising turn while also chastising the right for its indifference to African Americans.

He appeared on last week’s episode of The Brendan O’Neill Show to discuss his book and the issues it raises. What follows is an edited extract from the conversation. Listen to the full thing here.

Brendan O’Neill: How formative were the Vietnam War protests of the 1960s and 1970s in your political journey?

Glenn Loury: That movement was very important. I was raised by a working-class family in Chicago. When those protests began, I was a school drop-out and young father working at a printing plant. The factory was full of skilled, working-class tradesmen from largely Irish, Jewish and Italian backgrounds. They were blue-collar workers, not radicals. I identified with these men, despite the fact that I’m black and they were all white. There was a shared class bond.

Like them, I had a family to feed. I was always trying to get overtime, usually the second shift from 4pm until midnight, so I could put bread on the table. That was the world I belonged to in the late 1960s and early 1970s. I was working 40 hours a week plus overtime, tending to my family and studying at night. I thought of the radical, young protesters as pot-smoking kids. They weren’t my people. That was the crucible out of which my political heterodoxy developed.

O’Neill: What was it like to mix with these student radicals, including the black activists, when you eventually went to university?

Loury: I was originally at a community college, before eventually transferring to Northwestern University, Illinois in my third year. The community college was full of working-class people, many of whom couldn’t afford to attend fancy universities, trying to better their lives. I was one of them. The student body was also a mix of people from different racial and ethnic backgrounds. When I arrived at Northwestern University, thanks to a scholarship, I was introduced to an entirely new world. The elite, leafy-green campus was populated almost entirely by wealthy, upper-middle-class students. That was true not just of the white students, but of the black students as well.

I had a hard time relating to them. This was partly because I had a huge chip on my shoulder, but that wasn’t the whole picture. I was getting off work at 7am some mornings and driving straight through Chicago to attend my 9am class. Meanwhile, a lot of these students were just rolling out of bed after partying the night before. It seemed to me that their politics wasn’t rooted in any real-world experience. I thought about how, in my working-class neighbourhood, people I knew had friends in prison. I knew people engaged in various ‘marginal’ activities just to get by on the housing projects.

It was clear to me that student radicals were able to indulge their various political enthusiasms, without having to actually square it with the experiences of struggling people. I saw myself as someone trying to overcome disadvantaged origins, while many of my black compatriots knew next to nothing about the realities of life beyond campus.

O’Neill: Was your university experience an early example of the tensions between class politics and identity politics?

Loury: At that critical moment in the late 1960s and early 1970s, identity politics as we know it today was being born. The prerogatives of those who I called the ‘negro cognoscenti’ (elite, well-educated African Americans) were largely rooted in their status as members of an ‘oppressed’ group. They saw themselves as the persecuted descendants of slaves. The problem with this entire way of thinking, which is even more popular today than it was back then, is that it never considers the importance of class.

When I was working in the printing factory, I felt I had a lot in common with the people I was working with. They identified with me, too. This was not because we all belonged to some oppressed identity group, but because we were all trying to make a better life for ourselves and our families. I was coming from nothing and working my tail off, trying to scrape enough nickels together to put myself through school. I remember that, on one midnight shift, the foreman urged me to stop working on the noisy factory floor and use his office to type up a literature paper. Why? Because he identified with my struggle to improve my life, not my ‘oppressed’ background. An identitarian outlook can’t make sense of that.

In the long-run, those who are most interested in advancing the wellbeing of struggling, poor and disadvantaged African Americans do not play identity politics. Instead, they fashion politics in such a manner that black Americans can coalesce with the interests of other working peoples. Instead of basing everything on racial claims, we should focus our efforts on creating a better, more decent society. We should devise policies that promote the advancement of those who are actively trying to improve their lives – all those Americans who are struggling against the odds.

This kind of politics is universal and transcends identitarian boundaries. That’s the way that we should be looking at the world.

Glenn Loury was talking to Brendan O’Neill on The Brendan O’Neill Show. Listen to the full conversation here:

Melanie Phillips and Brendan O’Neill – live and in conversation

Wednesday 26 June – 8pm to 9pm BST

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

Picture by: YouTube.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.