How Sinn Féin became a party of the establishment

It has turned its back on its traditional voters – and is now paying the price.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

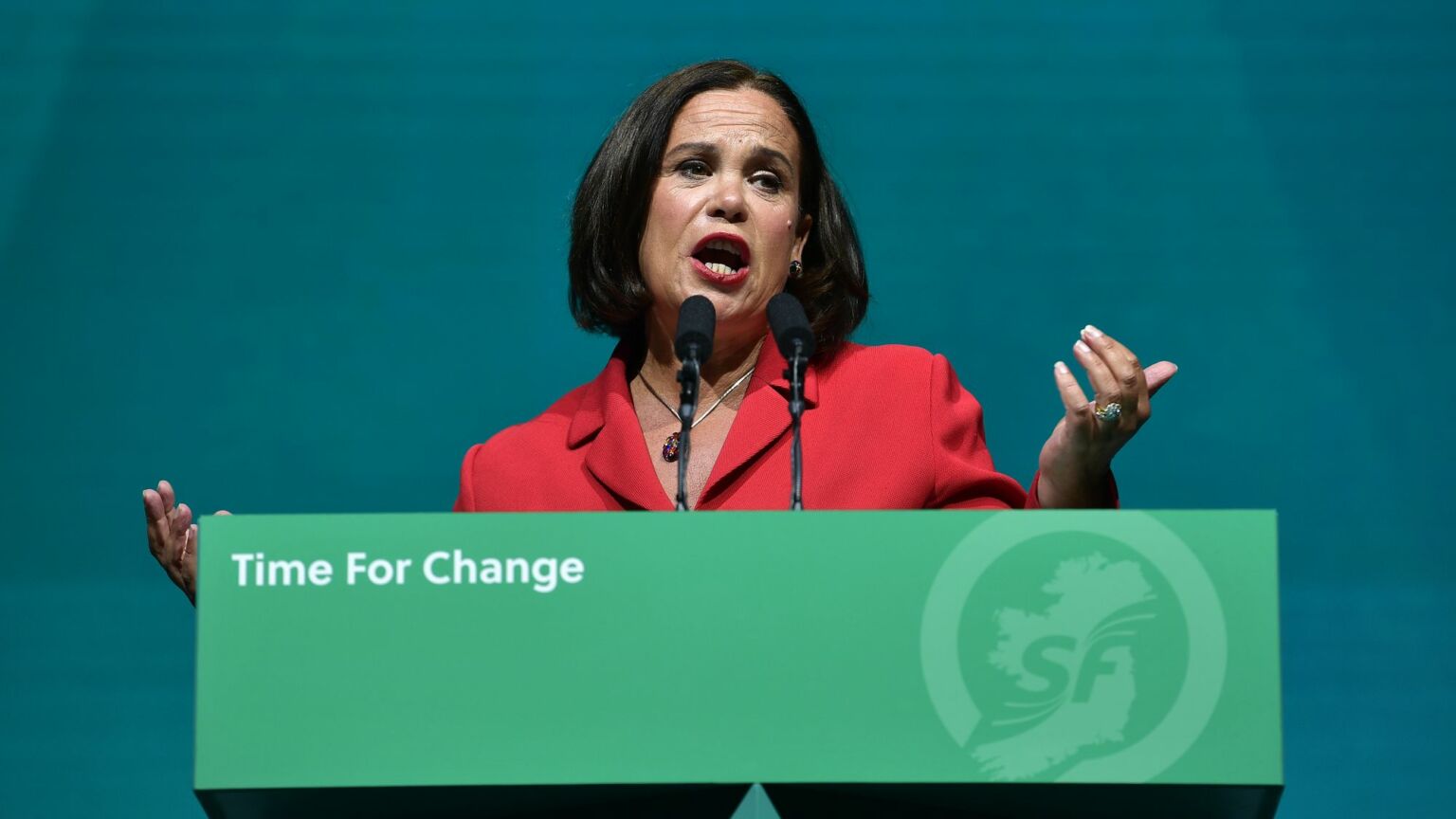

Not so long ago, a Sinn Féin government seemed all but certain in Ireland. In the closing months of 2022, it enjoyed a popularity rating of 36 per cent, which made it by far the most heavily supported party in Ireland. It looked set to leave all the other main parties trailing in its dust. It was only a matter of time before Mary Lou McDonald would become Ireland’s taoiseach.

In fact, the Shinners were so confident of romping home in the next election – which will likely be held later this year – that it wasn’t unusual to hear representatives loftily declaring all the changes they were going to introduce when they inevitably took power. The reasons for its success were clear and obvious.

By 2022, the Fine Gael / Fianna Fáil coalition had become unpopular with an increasingly disillusioned electorate. Top of the list of grievances, which Sinn Féin used to its advantage, was the unprecedented housing crisis. Many young Irish people now fear that they will never get to own their own home. Sinn Féin’s oft-repeated mantra, ‘It’s time for change’, resonated with many voters who felt their concerns were simply ignored by the two largest parties. In fact, at that point, Sinn Féin’s rise looked unstoppable.

But that was then and this is now. The current situation is far more precarious than the party could have ever expected. The latest polling, released last week, shows that Sinn Féin has fallen to 24 per cent, a precipitous decline since its heyday in 2022. The last five reputable opinion polls have all placed it below 30 per cent.

For this, the Shinners have only themselves to blame. Rather than making promises that might both energise the base and attract new supporters, Sinn Féin seems to have spent the past 18 months blundering into a series of landmines. This has taken it, in the eyes of many voters, from being the most viable opposition to the current coalition to being just another party of the establishment.

Take immigration. This has now replaced housing as the No1 concern for many voters. This development seems to have caught Sinn Féin completely by surprise. In its hunger to attract a more liberal, metropolitan voting bloc, it has been consistently pro-immigration. In a country that now has regular protests against accommodation for asylum seekers being provided in completely unsuitable areas, the normally canny and cunning Shinners simply failed to read the room.

Ireland is not a racist country. But as people see their community assets, such as hotels and sports halls, being taken over by the state and used to provide shelter for asylum seekers, resentment has grown to boiling point.

Yet according to Sinn Féin’s senior figures, anyone who opposes mass and uncontrolled immigration is simply a bigot. This convenient left-wing narrative may play well with those who live in the leafier areas of Dublin. But it has managed to alienate many of Sinn Féin’s older, more conservative, traditional and rural supporters, who are now in open revolt against their own party.

Without that traditional base, the party is left relying on younger voters who were born after the Good Friday Agreement was signed in 1998, and who simply don’t care about the party’s legacy from the Troubles. That simply won’t be enough to get Sinn Féin over the line at the next election.

But it’s not merely the vexed issue of immigration. Sinn Féin seems to have dropped the ball on numerous other issues as well. It supported this month’s two ruinous constitutional referendums, on changing the definition of the family and the rights of domestic carers in the Irish constitution. These were proposed by the coalition government which, like Sinn Féin, was confident that both motions would pass with ease.

Instead, the ‘care’ referendum was rejected by an historic 74 per cent of voters, while the proposal to redraw the definition of the traditional family was beaten by 67 per cent. These were the worst referendum results ever suffered by an Irish government.

Not only were the results an absolute disaster for the government – and likely the main contributory factor to taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s resignation the following week – but Sinn Féin’s leaders also found themselves caught in the splatter. This created a most unusual position for a party that had always been keen to stay on the populist side of politics.

The party’s confusion about what it actually stands for, as opposed to merely getting into power, became even more apparent this week when it announced it would no longer back the government’s hated Hate Crime Bill.

This draconian piece of legislation would, among other things, make it a crime simply to be in possession of offensive material. It was supported by Sinn Féin in a Dáil vote last April. But the party has now changed direction. Many of its senior members are even calling for the whole thing to be scrapped. Of course, they insist that they always had reservations about the bill. But they still can’t explain why they have now performed such a drastic reverse-ferret.

So why have Sinn Féin’s fortunes started to decline so sharply? One simple explanation may be that it had always relied on floating voters being more annoyed with the government than they are with Sinn Féin. The party would make grandiose promises on housing and the economy that, while utterly unworkable in the cold light of day, attracted people who were simply angry with the status quo. But there’s not much point in being an ‘anti-establishment’ party when many of your policies now put you on the same side as that establishment.

Sinn Féin can still take consolation from the fact that it remains the most popular individual party in Ireland. But to get into government with such a low vote share, it will need to form a coalition – and the main parties have been quite clear that they will refuse to take part.

Indeed, it was interesting to note that one of the first things Simon Harris did this weekend, upon replacing Varadkar as taoiseach, was launch a series of broadsides against Sinn Féin. In his first speech, he said that he wants ‘to take our flag back’. This was in response to the former IRA member and Garda killer, Pearse McAuley, being buried recently with a tricolour on his coffin. In the 1990s, Sinn Féin fought for him to be released early from prison.

Sinn Féin’s leaders might try to distance themselves from their past. But their past has an unfortunate habit of coming back to haunt them.

Ian O’Doherty is a columnist for the Irish Independent.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.