Who’s afraid of Wegovy?

An easy fix to obesity is staring us in the face – so why are weight-loss drugs still so controversial?

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Obesity is a seemingly intractable problem. Losing the spare tyre and keeping it off is far easier said than done. Meanwhile, public-health types insist – on the basis of very questionable figures – that our weight issues are a drain on the economy and the health service, too. Something must be done, they insist.

So you would think everyone would be delighted about the arrival of new weight-loss drugs. Recently, semaglutide, a class of drugs normally used to treat diabetes, has been repurposed to help with weight loss. But while it has been acclaimed by those who had previously struggled to lose weight, it has been met with much tut-tutting from nanny statists. Apparently, taking these drugs is the ‘wrong’ way to lose weight.

The traditional approach to weight loss is that, one way or another, you eat less and / or move more. For those with sufficient motivation, cutting calories consumed and increasing calories expended can indeed result in weight loss. But there is a big natural barrier to be overcome when losing weight and keeping it off – namely, hunger.

Semaglutide is part of a class of drugs that mimics the effect of the GLP-1 hormone, which is released in the gut after eating. The effect is to reduce your appetite, thus removing that most monumental obstacle to shifting the pounds.

The sheer power of hunger should not be underestimated. In his 2008 book, Good Calories, Bad Calories, author Gary Taubes describes an experiment conducted in 1944 by physiologist Ancel Keys and colleagues at the University of Minnesota. The aim was to observe the effects of the famine diets that were then being experienced by many in war-torn Europe. The volunteers, all men, were restricted to 1,570 calories per day (for comparison, the current recommendation for men is 2,500 calories) and were asked to walk five or six miles per day.

Quickly, the men became obsessed with food. Their blood pressure and pulse rates fell and they began to feel cold, even when wrapped up. One or two effectively suffered breakdowns as a result of this semi-starvation. All ate ravenously when allowed to do so, piling on the weight quicker than they had lost it. They even ended up heavier than before the programme started.

Calorie-restrictive diets are the bread and butter, as it were, of most weight-loss programmes. Yet so many people, even if they have lost substantial amounts of weight by suppressing the desire to eat, suffer the depressing reversal of that weight loss when they attempt to normalise their diets.

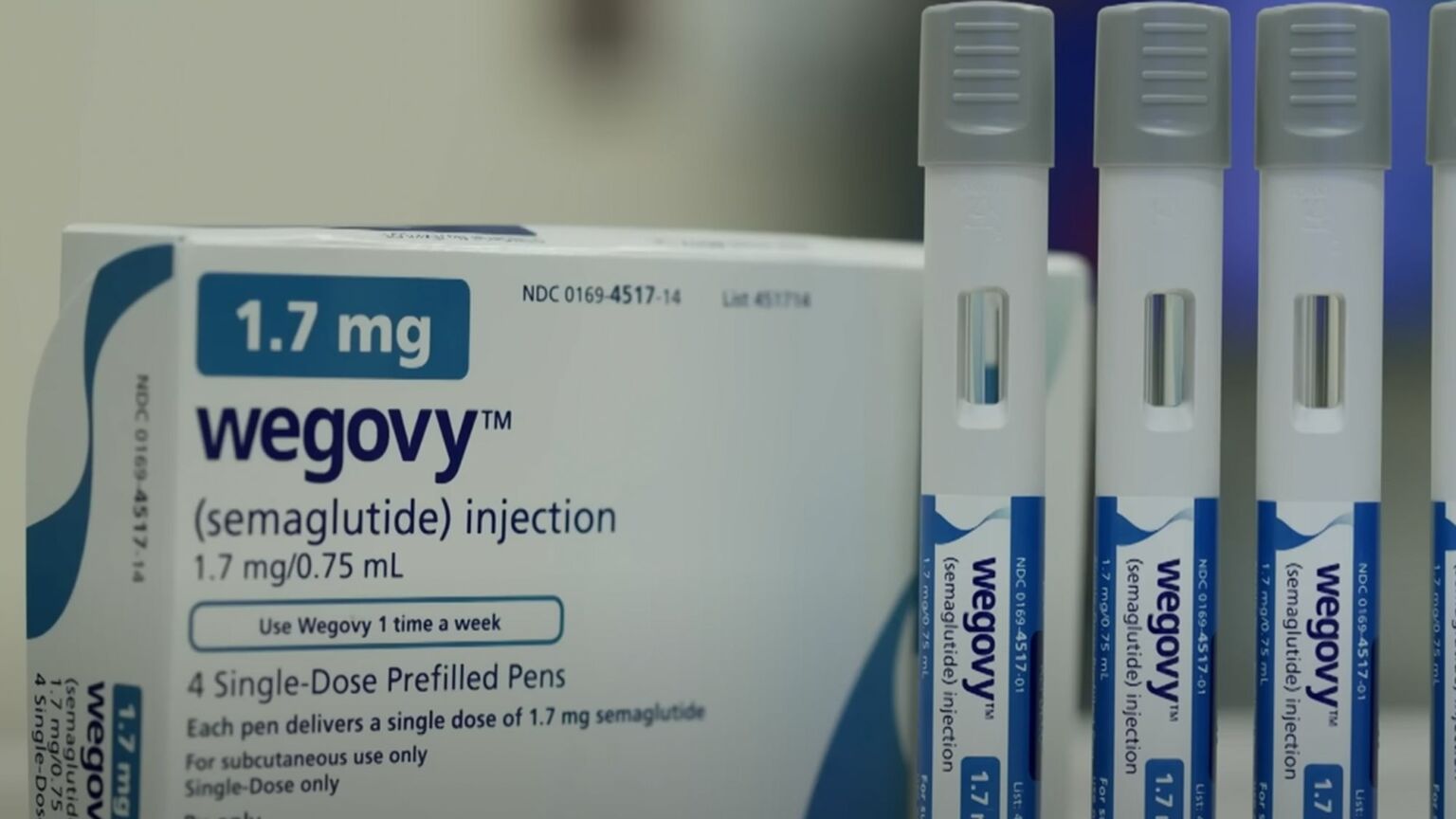

That means anything that can reduce the horrible feeling of hunger is a boon to those trying to keep off the pounds. Semaglutide – marketed as Ozempic for diabetes and, in higher doses, Wegovy for weight loss – has proven to be very successful in this regard. Users still have to adjust their calorie intake, but doing so is a lot easier with a smaller appetite.

Of course, such drugs don’t guarantee weight loss. And in the long run, there is always the risk that the weight will come back – particularly as current UK guidance suggests semaglutide should only be used for two years. Nevertheless, the development of these drugs is undoubtedly a step in the right direction.

Finding a safe and effective drug that can help with weight loss has been an aim of the pharmaceutical industry for decades. Previous attempts have tried to use amphetamines or related compounds to suppress appetite. But the long-term effectiveness of those drugs is limited and the side effects can be severe. For example, the combination of fenfluramine and phentermine (colloquially called ‘fen-phen’) was a common treatment for obesity in the early 1990s. But it soon became clear that it was linked to heart-valve problems and was subsequently banned.

If the new breed of appetite-reducing drugs prove to have sustained benefits for weight loss and are safe in the long term, they could be extremely beneficial. After all, despite the recent movement for body positivity, which insists we can be ‘healthy at every size’, being very overweight is at best inconvenient and at worst a serious health risk.

So it’s no wonder that these drugs are being widely embraced. In February 2022, the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) began recommending semaglutide for weight loss. And since September of this year, the NHS has begun a ‘controlled and limited launch’ of Wegovy for those in the greatest need.

Celebrities have also sung the praises of semaglutide. Last week, Oprah Winfrey revealed in an interview with People magazine that she is now using the weight-loss drug. Her experience is typical of many people. She said her previous attempts to lose weight had ‘occupied five decades of space in my brain’. She was only able to get a handle on her weight with semaglutide.

Yet others have been more disapproving. Founder of fast-food chain Leon and former UK food tsar Henry Dimbleby declared in April that Britain cannot not ‘drug its way out of the problem’ of obesity. While he is not opposed to prescribing Wegovy to those suffering with serious health problems, he has argued that the UK should instead look to the ‘very interventionist’ approaches of Japan and South Korea to get a handle on obesity. In Japan, for example, overweight employees are sent on weight-management courses by employers. This is effectively state-mandated fat-shaming.

Dimbleby’s recommendations are certainly interventionist. In his report for the National Food Strategy in 2021, he argued for a ‘£3 / kg tax on sugar and a £6 / kg tax on salt sold for use in processed foods or in restaurants and catering businesses’. This would be, in effect, an extension of the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (aka the sugar tax) that came into force in 2018. This has made some soft drinks more expensive and has ruined the taste of others, as sugar has been replaced with artificial sweeteners.

In its five years in operation, the sugar tax has only led to vanishingly small changes in average calorie intakes. Last week, a research paper in the British Medical Journal had to be retracted after wrongly claiming that the levy had cut sugar consumption by 30 grams per household per week. The real figure was only eight grams.

When faced with a choice between ineffective, authoritarian measures and a safe, effective weight-loss drug, why do so many still push for the nanny-state option? Sometimes the ‘easy’ way really is the best way.

Rob Lyons is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: YouTube.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.