How the radical left learned to love state censorship

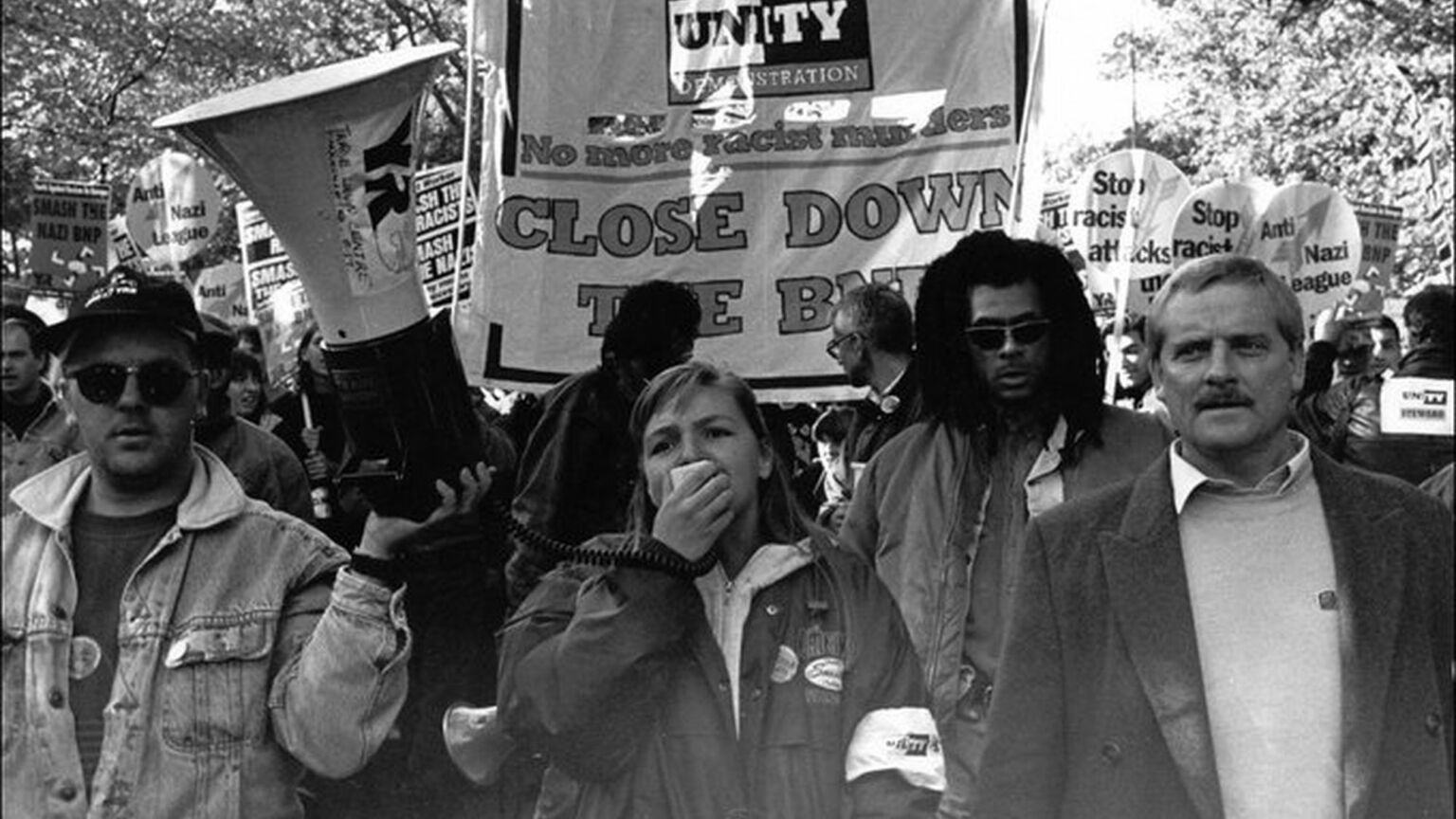

In the Welling riots 30 years ago, phoney anti-fascists laid the groundwork for today’s free-speech wars.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Thirty years ago, far-left activists gathered in Welling, east London, to demand the closure of a bookshop owned by the far-right British National Party (BNP). Attending that day as part of a group called Workers Against Racism, I can remember hearing a protester bellowing through a megaphone, ‘Where are the BNP? They’re not here! We have driven the fascists out from east London!’

The protesters certainly didn’t find the BNP on 16 October 1993. But, as they tried to approach the BNP bookshop, they did encounter resistance from the police. Tensions between the protesters and the police soon turned violent. In total, 74 people were injured in what became known as the Welling riots. This was the most serious case of civil disorder in the UK since the poll-tax riots in 1990.

The main far-left organisers of the Welling demonstration – the Socialist Workers Party’s (SWP) Anti-Nazi League and Militant Tendency’s Youth Against Racism in Europe – have long celebrated the Welling demo as a decisive blow against the BNP and fascism.

In truth, however, it wasn’t much of a victory. The SWP and Militant Tendency had spent much of the previous year inflating the threat of the BNP. It was neither a mass organisation nor a paramilitary outfit. Indeed, the BNP only ever managed to muster, at most, a few hundred boneheads for its street protests. Racist attacks were certainly still a problem in east London at the time. But the days of large, mobilised far-right organisations were already long gone by the early 1990s.

The hard left’s obsession with an organisation as insignificant as the BNP was born of a desperation to appear relevant. The collapse of Communism between 1989 and 1991 had disoriented and disillusioned many on the left, and their project of radical social transformation had become irrelevant to the masses. So to gain some currency with idealistic middle-class youth, far-left groups began to mobilise against the spectre of fascism. In 1992, the SWP revived the Anti-Nazi League, a 1970s campaign against the National Front. That same year, Militant Tendency launched Youth Against Racism in Europe, as a rival to the Anti-Nazi League.

While the Welling demo may not have contributed to any real struggle against fascism, it was significant for other far less radical reasons. It was the point at which the broader hard left revealed its willingness to embrace political censorship. The point at which it started calling on the state to decide what people can and can’t say. The point at which the middle-class, students’ union politics of No Platform became the politics of the radical left. Here we had nominally left-wing revolutionaries calling on the state to shut down a bookshop. It was quite shocking to witness at the time.

My comrades in Workers Against Racism were all too aware of the dangers state censorship posed to the radical left. We countered the would-be censors on the demo with the slogan, ‘Fighting racism, it’s up to us’. We were making the case for maintaining political independence from the authorities. Yet our campaign was met with considerable hostility on the demo. And the warning went unheeded.

The following year, the Metropolitan Police made their first tentative steps towards presenting themselves as an ‘anti-racist’ force, by launching the Black Police Association. Meanwhile, left-wing activists began demanding that employers sack workers who were BNP members. The Welling demo had provided an ominous glimpse into how politics was going to take shape over the next three decades.

These were the forces that would later culminate in cancel culture and the prohibition of so-called hate speech. The state, cheered on by the once radical left, was starting to pose as the champion of minorities. And it was pitching itself against a supposedly racist working class.

Indeed, after the tragic and senseless murder of Stephen Lawrence in April 1993, the hard left began labelling the white working class as a racist threat. At the time, the Anti-Nazi League even handed out leaflets presenting council estates – complete with an image of a rat – as rich pickings for BNP activists. I can even remember an anti-BNP demonstration in Manchester in April 1994, in which activists inexplicably started to chant ‘Fascists off our streets’ at working-class Manchester City fans drinking outside a pub in Rusholme.

It was perhaps not clear at the time, but new battle lines were being drawn, between the state supported by a middle-class left, and vast swathes of working-class Britain.

Through anti-racist campaigns, the left had historically forged class-based solidarities that transcended ethno-cultural divisions. But after the Welling demo, anti-racism had started to turn into something else. It was now a means by which the state could justify its power over working-class people, its intervention into their everyday lives and its censorship of speech.

Those protesters 30 years ago may have thought they were fighting fascism. But in reality, they were only empowering the state.

Neil Davenport is a writer based in London.

Matthew Goodwin and Brendan O’Neill – live and in conversation

Wednesday 20 December – 6.15pm to 7.15pm GMT

This is a free event, exclusively for spiked supporters.

Picture by: Twitter.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.