Long-read

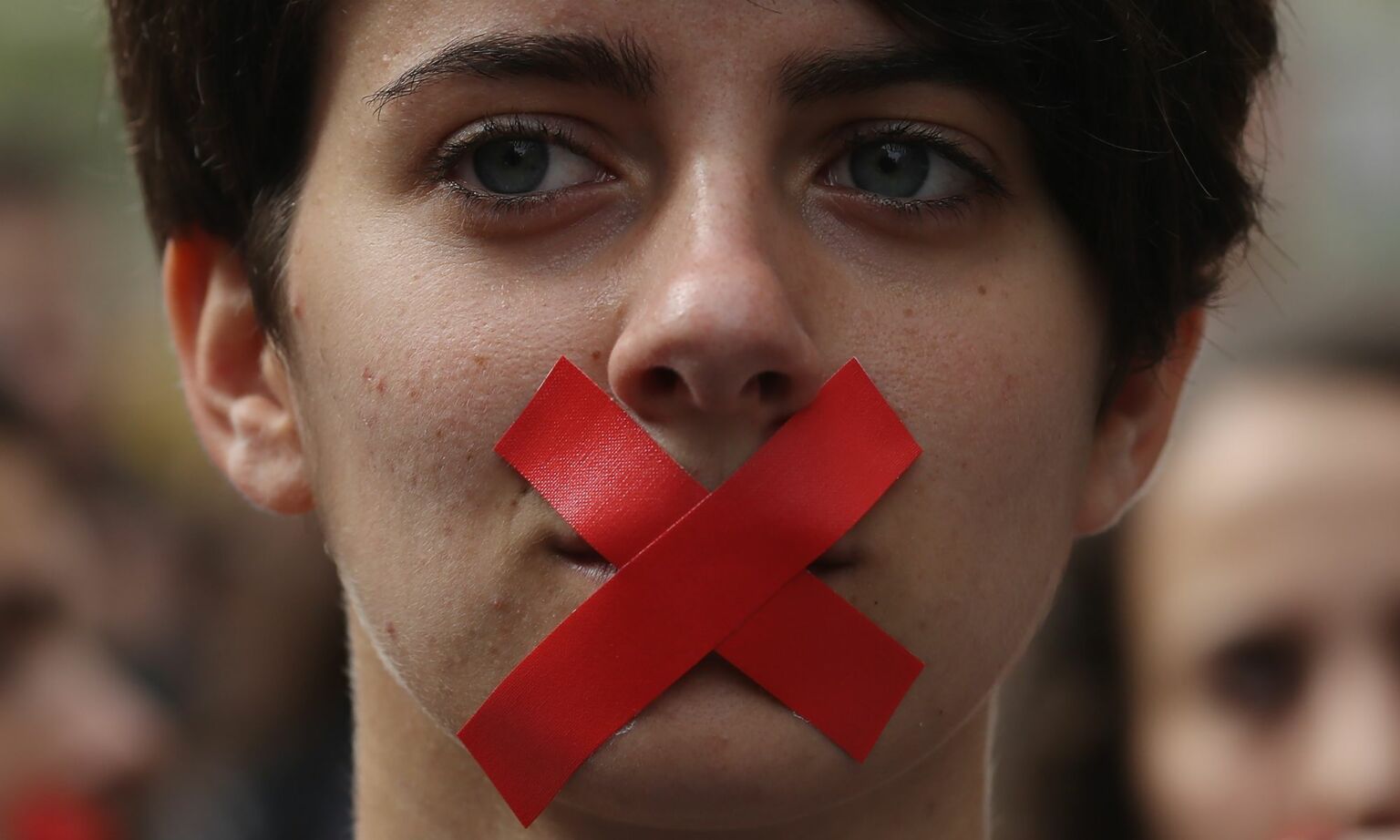

The left’s dangerous embrace of cancel culture

Identitarians believe they're speaking truth to power. They're not.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The semantic history of the term ‘cancelled’ isn’t difficult to trace. It was first used in its contemporary meaning as a line in the 1991 American crime thriller, New Jack City. It reached a wider audience with an episode of VH1’s popular reality show, Love and Hip-Hop: New York, which aired on 22 December 2014 to 2.17million viewers, where one of the characters tells his girlfriend, ‘You’re cancelled!’, during a heated outdoor fight. The term then seeped into ‘Black Twitter’, and from there to the broader public, where it morphed into a lexical weapon to galvanise opposition to perceived offences, in particular those committed by celebrities or other powerful figures, often accompanied with a call for boycotts.

The final seal of approval came from the Oxford English Dictionary, which introduced a new, colloquial definition of the term ‘cancel’ in March 2021: ‘To dismiss, reject or get rid of (a person or thing). In later use, especially in the context of social media: to publicly boycott, ostracise or withdraw support from a person, institution, etc thought to be promoting culturally unacceptable ideas.’ There is also an entry on ‘cancel culture’: ‘The action or practice of publicly boycotting, ostracising or withdrawing support from a person, institution, etc thought to be promoting culturally unacceptable ideas.’

But what are ‘culturally unacceptable ideas’? Who, or which authority, decides what is culturally acceptable and what isn’t at any given point in time? And what should be the left’s stance vis-à-vis culturally unacceptable ideas, whatever they may be? This last question was the one that matters most to me because, as a card-carrying progressive, I’m not particularly interested in the right.

From the way it is defined by the OED and other sources, ‘cancel culture’ seems to be nothing more than the latest incarnation of censorship and witch hunts – the hallmarks of reactionary, conservative thinking throughout centuries. The problem is that cancel culture is practised by progressive circles as well, in particular those who embrace some form of radical identity politics. Certain ideas have become culturally inappropriate for the left, it seems, and it is now up to the self-appointed guardians of the new orthodoxy to ensure that they remain inappropriate. Cancelling is seen as a means to a higher end, and in the alternate universe of the contemporary left, the end always justifies the means.

There are three types of responses to cancel culture on the left. Some simply believe that cancel culture doesn’t exist. They portray it as a myth, or the proverbial monster under the bed. Others treat it as an example of a moral panic instigated by the right, arguing that those who are on the receiving end of cancel campaigns don’t actually suffer any real-life consequences. These versions of cancel-culture denialism are like Flat Earthism — frivolous and too easy to debunk. But the third and final response to cancel culture on the left makes a serious case for it, hence it needs to be properly engaged with.

For a good number of its defenders, cancel culture is about accountability and agency. It’s about dismantling existing power relations, and conferring authority on to the lived experiences of oppressed people. These left-wingers claim that cancel culture is not an attack on free speech, but a reminder that speech has consequences, and that traditionally privileged individuals should be treated like everyone else.

There are several problems with these arguments. First, they are all based on a static understanding of power relations. This presumption is still true on a systemic level – people of colour, women, LGBTQ+ people and the poor do indeed face more discrimination – but that does not explain individual cases. Not all attempts at cancelling can be read as a last-ditch appeal for justice by the powerless. On the contrary, in some cases, it is not until ‘the powerful’ take up the cause that these attempts gain momentum.

Take #MeToo, for instance. The original, unhashtagged ‘Me Too movement’ was founded by Tarana Burke, a black civil-rights activist in the Bronx, who was herself sexually abused and raped as a child and teenager. In 1997, after a young girl told her that she’d been abused by her mother’s boyfriend, she didn’t know what to say. Afterwards, she wished she’d said, ‘Me too’. This led her to found first the non-profit organisation, Just Be Inc, for girls from minority groups aged between 12 and 18, which is, as its website states, ‘focussed on the health, wellbeing and wholeness of brown girls everywhere’. Then, in 2006, she founded the Me Too movement, using a MySpace page.

Yet the movement only went viral on 15 October 2017, after the white American actress Alyssa Milano created the hashtag #MeToo to draw attention to the sexual assault and harassment of women in Hollywood. Her message was retweeted nearly a million times in 48 hours, and spread to other social-media platforms like Facebook, where it was shared more than 12million times in 24 hours.

Was this a case of punching up? It was, but nobody heard about it until a white woman with privilege and a large platform took over the movement. Was it a victory for the powerless? It undoubtedly brought down several powerful abusers like Harvey Weinstein and Bill Cosby. But it was not all black-and-white. As its original founder, Tarana Burke, commented in an interview she gave in 2018, #MeToo also brought ‘this extreme backlash’. The hashtag brought with it a sense that it had become ‘a witch hunt’, Burke said. ‘Basically, just watching the idea of Me Too become weaponised has been a challenge’, she added.

Second, power dynamics change, even at the systemic level. Transgender people are still a disadvantaged group, especially if they are also non-white and poor. But there is also an influential trans-rights movement today, involving major charities like Stonewall (with over 900 organisations across the UK registered in its Diversity Champions programme) and Mermaids; NGOs, such as GLAAD (Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) in the US; and, in addition to these, friendly governments and politicians, media organisations, lobby groups and multinational corporations. It is telling that most ‘progressive’ commentators who purportedly reject cancel culture are also its foremost practitioners when it comes to debates over trans rights, leading cancel campaigns against women, lesbians and, yes, transgender people, for raising concerns about certain aspects of trans-rights activism, or even the definition of the term ‘woman’.

Third, it’s not only celebrities or the powerful who become the target of outrage mobs. Ordinary people are cancelled too, for posting an off-the-cuff comment, inadvertently using a politically incorrect term, or being on ‘the wrong side of history’ without even knowing what the right and the wrong sides are.

Few had heard of Justine Sacco, the senior director of corporate communications at IAC, a holding company that owns the Daily Beast, OKCupid and Vimeo, until she shared a tacky tweet with her 170 followers, during a layover at Heathrow on her way to South Africa on 20 December 2013. ‘Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get AIDS. Just kidding. I’m white!’, she wrote. She then boarded her plane and slept through an 11-hour flight. She turned on her phone again when the plane landed in Cape Town, only to realise that her tweet had gone viral. Among the thousands of comments, there was one by a co-worker who said, ‘I’m an IAC employee and I don’t want @JustineSacco doing any communications on our behalf ever again. Ever.’ This was followed by a tweet from Sacco’s employer: ‘This is an outrageous, offensive comment. Employee in question currently unreachable on an [international] flight.’

The anger soon turned into excitement, notes journalist Jon Ronson, who interviewed Sacco for his book, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed. A hashtag began trending worldwide: #HasJustineLandedYet. Some people even found out which flight she was on and linked the hashtag to a flight-tracker website so that everyone could watch its progress in real time. Within 24 hours, she had been fired.

During the 11 days between 20 December and the end of December, Sacco’s name was googled 1,220,000 times (up from 30 the previous months). It took months for Sacco to find a new job. But the internet never forgets. At the time of writing, the infamous tweet is still the first thing we encounter when we type her name into a Google search. There is no statute of limitations for either the cancellers or the cancelled.

Finally, the narrow focus on power relations also conceals the protagonists’ own privileged positions. Almost all outspoken defenders of cancel culture are themselves prominent intellectuals or public figures, not random bloggers or hapless victims of systemic oppression with no other platform than an anonymous Twitter account. Indeed, what if cancel-culture defenders are themselves the new elites? They don’t just populate university campuses. They are also part of the legacy media, the culture industry and a significant part of the corporate world.

It’s true that there are several reactionary outlets with desks devoted to digging out every cancellation attempt in the US and the UK. But we also have an equal number of so-called progressive platforms with counter-insurgency units ready to be activated the moment a cancel attempt makes right-wing headlines – either defending the cancellation or denying it constitutes a cancellation at all. We do not know the extent to which these leftish outlets are concerned with the wellbeing of marginalised groups, but we can safely assume that they care for profit, the main driver of identity politics of all hues.

Does all this mean that we should refrain from calling out systemic injustices or examples of prejudice when they rear their head? Of course not. But cancel culture is not criticism. The differences can be sometimes difficult to observe in practice, but as American author and journalist Jonathan Rauch reminds us in his 2021 book, The Constitution of Knowledge: A Defence of Truth:

‘Criticism seeks to engage in conversations and identify error; cancelling seeks to stigmatise conversations and punish the errant. Criticism cares whether statements are true; cancelling cares about their social effects… Criticism is a substitute for social punishment (we kill our hypotheses rather than each other); cancelling is a form of social punishment (we kill your hypothesis by killing you socially).’

Cancel culture is really a conflict over what can and cannot be said, and who makes that decision. And it is here that the reactionaries and the progressives team up, as both fight to determine what is and isn’t culturally acceptable. Hence the right is completely blind to reactionary cancel campaigns or, more generally, the assault on fundamental rights and freedoms by conservative legislatures and executives all around the world. And radical identitarians are more concerned with policing speech and identifying microaggressions among fellow progressives than building a common front against the right’s transgressions. The left is invariably oblivious to egregious breaches of fundamental freedoms when they are committed by what they perceive as disadvantaged groups, claiming the authority to determine who the victims and the perpetrators are. This move allows them to create a false moral binary between freedom of speech on the one hand, and the sanctity of life on the other.

But why do new left-wing activists retreat into performative outrage and virtue-signalling instead of fighting for real change? One answer to this question can be found in the seminal book by academics Jeffrey M Berry and Sarah Sobieraj, The Outrage Industry: Political Opinion Media and the New Incivility. Outrage provokes emotional responses from the audience, the authors argue, through the use of ‘overgeneralisations, sensationalism, misleading or patently inaccurate information, ad hominem attacks, and belittling ridicule of opponents’. More importantly, it ‘sidesteps the messy nuances of complex political issues in favour of melodrama, misrepresentative exaggeration, mockery and hyperbolic forecasts of impending doom’. It creates a safe space for those who think alike, not only reducing potential risks for the participants, but also producing a sense of community and belonging, by isolating them in echo chambers. And, as a result, outrage kills politics.

The contemporary left is now undermining itself. It needs to break the outrage cycle, and develop a genuinely progressive social and economic vision, instead of attempting to cancel its opponents. That is the only way to really tackle inequality and injustice.

Umut Özkirimli is a senior research fellow at IBEI (Institut Barcelona d’Estudis Internacionals), a professor at Blanquerna, Ramon Llull University, and a senior research associate at CIDOB (Barcelona Centre for International Affairs). He is the author of Cancelled: The Left Way Back From Woke, Polity, 2023.

Umut will be speaking at the Free Speech Union live-stream event, ‘Is there a left way back from woke?’, at 7.30pm on 13 September. For more details, see here

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.