Kids don’t need teachers who ‘look like them’

The notion that black pupils must be taught by black teachers is racialist nonsense.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

New research from Durham University’s Evidence Centre for Education shows that pupils in certain parts of England are unlikely to ever have a teacher from the same racial or ethnic background as them. Professor Stephen Gorard, the centre’s director, claims this is having a ‘considerable impact’ on ethnic-minority pupils. ‘Not being taught by someone who sounds and looks like them could affect pupils for things like suspensions and exclusions, the categorisations for special needs, their absence and their happiness, expectations and aspirations’, he told the Guardian last week.

Gorard’s claims may have generated some headlines. But they appear to be contradicted by the research itself. Durham University’s new study shows that the number of teachers from black-Caribbean backgrounds has risen over recent years and is now proportionate to the number of black-Carribbean pupils nationally. Given the report’s assertion that having teachers of the same race corresponds to an improvement in pupils’ educational attainment, one might therefore expect black-Carribbean pupils’ performance to have improved in recent years.

But that has not been the case. The available statistics continue to show that pupils from a black-Carribbean background are consistently one of the worst-performing groups in the English school system. For the 2020-21 academic year, the average ‘Attainment 8’ score (across eight GCSE-level qualifications) for pupils of black-Caribbean origin was 44.0 (out of 90) – only pupils from Gypsy / Roma and Irish-traveller backgrounds scored lower. In 2021-22, the rate of suspensions for pupils of black-Caribbean origin was 12 per cent, which is also high compared with previous years.

Having teachers of the same ethnic background does not appear to be leading to positive outcomes for pupils of black-Caribbean origin. This shows that the ethno-racial identity of teachers is clearly not the magic bullet the researchers claim it is.

The claims made for racial and ethnic representation among teachers fall apart further when you look at the performance of pupils of Bangladeshi origin. In 2021-22, just 0.7 per cent of schoolteachers in England were of Bangladeshi origin, compared with two per cent of pupils. Bangladeshi-heritage teachers are therefore ‘under-represented’ in English schools.

But that doesn’t seem to be affecting pupils from a Bangladeshi background. They are now one of the stronger-performing groups in England, with an average Attainment 8 score in 2020-21 of 55.6 (11.6 points higher than their black-Carribbean peers). The same goes for pupils from black-African communities. In 2021-22, just one per cent of schoolteachers were of black-African origin, compared with four per cent of pupils. Yet, these pupils still performed notably better than their peers of black-Caribbean origin, and are less likely to be suspended and excluded.

It’s clear that the ethnic composition of the teaching profession is not really shaping kids’ educational outcomes at all. Far more important are factors like family stability, and the value attached to education in the household and the wider community. Among families of Indian and Chinese origin, for example, educational success is widely viewed as the most effective springboard towards future financial security. Hence, pupils from Indian or Chinese backgrounds tend to do better than peers from other backgrounds.

More importantly, it’s also clear that the skill and character of schoolteachers matters far more than their ethnic or racial background. That’s also why pupils from Bangladeshi backgrounds are doing well educationally. They are benefitting from recent improvements in teaching standards in schools in London’s eastern boroughs, where many Bangladeshi-origin communities reside. Schools there have started to hire ambitious and energetic teachers of all backgrounds who have come through various innovative teacher-training programmes, such as Teach First.

If ethnic representation in the teaching profession really shaped educational outcomes, then white-British children would be one of the highest-performing groups in England. But they’re not. In fact, pupils from a white-British background lag behind a variety of non-white ‘under-represented’ groups. The level of school attainment is particularly low in the places like Knowsley and Blackpool in north-west England, where pupils and teachers come overwhelmingly from a white British background.

There are many social, economic and cultural factors that shape pupil performance in English schools. But the racial and ethnic identity of schoolteachers isn’t one of them. If we’re serious about improving educational outcomes for all children, we need to leave racial identity politics behind.

Rakib Ehsan is the author of Beyond Grievance, which is available to order on Amazon.

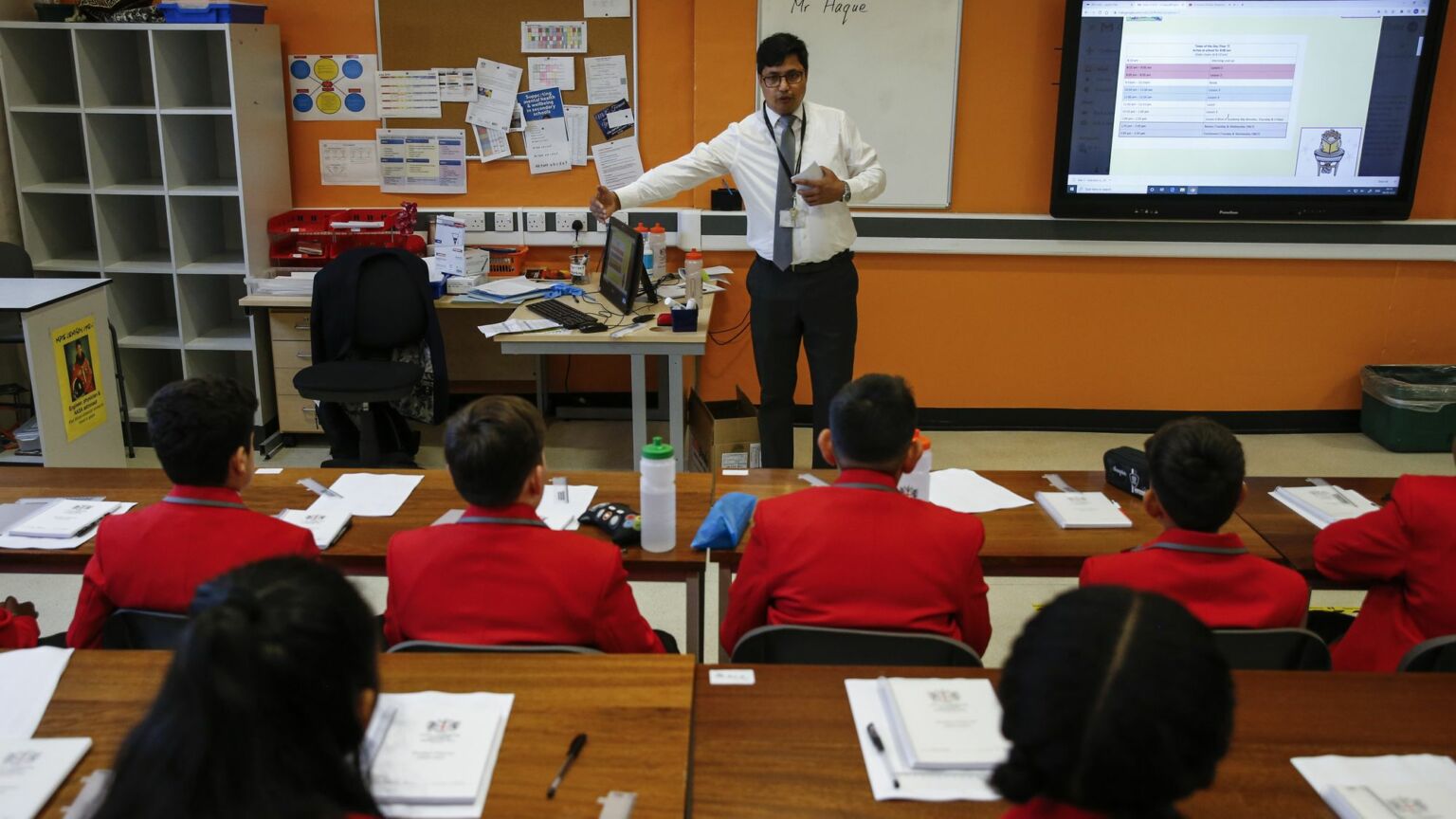

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.