Syriza and the exhaustion of left populism

From Greece to Spain to Britain, left-wingers have completely failed to seize the populist moment.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Much of the commentary on last weekend’s Greek elections has focussed on the success of the right. The conservative New Democracy party has won a second term on 40.5 per cent of the vote. And to its far right, the recently formed Spartans party – backed by supporters of the now banned Nazi tribute act, Golden Dawn – has secured five per cent of the vote. There were similar, small-scale victories for a host of far-right groups, which, like the Spartans, will also enter the Greek parliament.

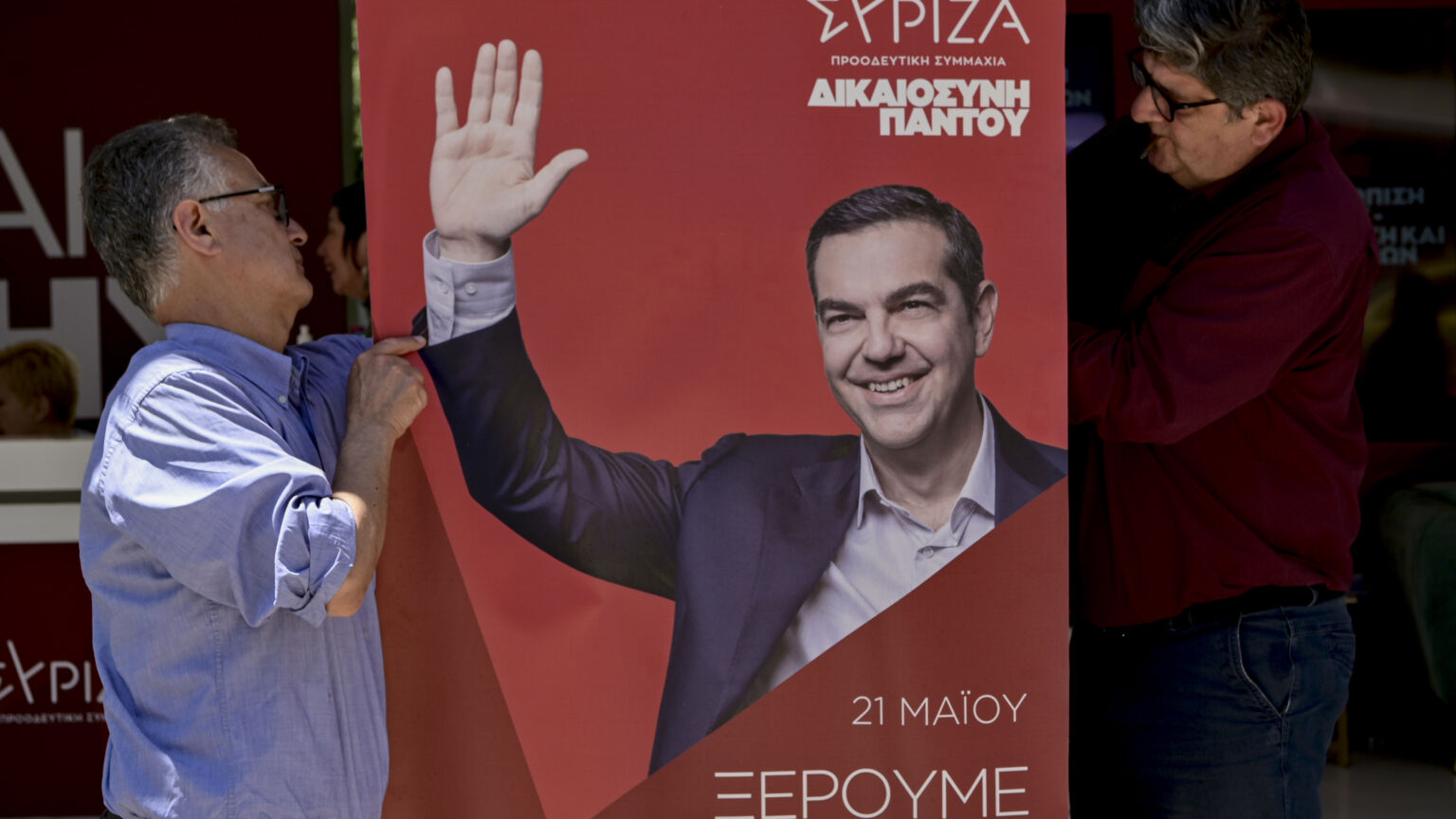

Ultimately, New Democracy’s success has less to do with any resurgence of the right than in the total collapse of the left. Syriza, a left-wing coalition, was the dominant force in Greek politics for much of the late 2010s. It came from almost nowhere to win the 2015 elections, and remained in power until 2019. Yet it now looks as if its race is run. Syriza picked up just 17.8 per cent of the vote at the weekend, down from 32 per cent in 2019. Its leader and one-time prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, cut a dejected figure on Monday morning. ‘We have suffered a serious electoral defeat’, he admitted. He added that his future would be decided by Syriza members.

Syriza’s defeat is not just significant for Greece, however. It also illustrates the Europe-wide exhaustion of what was once talked up as a new left-wing populism.

Back in 2014, it all looked so different. Syriza was insurgent. It claimed to represent a genuinely populist opposition to the harsh austerity measures that followed the Eurozone crisis of the early 2010s. Its relatively young, firebrand leaders, Tsipras and Yanis Varoufakis, talked of taking on the EU. They said they would refuse to accept the punishing conditions that were attached to the bailouts on offer from the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund – the so-called Troika.

This proved popular with voters. In January 2015, this obscure left-wing coalition won the Greek elections. Basking in the afterglow of victory, Tsipras stood up in front of the Greek people and pledged to end ‘five years of bailout barbarity’. Syriza’s triumph, he continued, was a ‘defeat for the Greece of the elites and oligarchs’.

In retrospect, this was the high-point of Europe’s left-populist moment, which in time proved itself to be neither particularly radical nor genuinely populist. Tsipras stood at a podium in Athens, backed by millions of voters, railing against ‘the elites and oligarchs’, slamming the EU and the forces of capital. It was defiant, hopeful and, for many, inspiring. It was also completely empty.

Within just a few weeks, Syriza capitulated to the demands of the ‘elites and the oligarchs’. In the so-called 20 February agreement, Syriza agreed to EU-determined budget cuts and public-sector reforms, and to meet all of Greece’s debt obligations in full. In return, the European Central Bank would lend it some cash.

This turned out to be the modus operandi of Tsipras and Syriza. They would bluster about resisting the EU’s harsh demands. They would promise to shake off the fiscal straitjacket of austerity. But in practice they would acquiesce at every key moment. They did so after a referendum in July 2015, when the Greek public voted to reject the Troika’s bailout conditions, only for Tsipras, a few days later, to accept the Troika’s terms in full. And they did so again in August 2018, when the Eurogroup imposed budget-surplus targets of 2.2 per cent of GDP or more until 2060 (meaning that state revenue must be greater than spending every year for the next several decades).

This was the story of Syriza’s time in power. It struck left-wing poses while doing the bidding of the Troika, it channelled populist fury before throwing ordinary people under the bus. It sold off airports, railways and large segments of the energy grid. And it auctioned off the homes of families unable to pay their debts to the banks. All to meet the budgetary targets set by external actors.

Syriza’s failure was not an aberration, however. Its actions were similar to those of other left-populist upstarts, such as Podemos in Spain. They shared the same rhetorical commitment to opposing austerity while, in practice, committing themselves to remaining within the EU – the very institutional framework that was pushing austerity measures on them. Their economic promises depended on exercising a degree of national sovereignty – sovereignty that was undermined by their membership of the EU. They indulged in radical posing. And they were often supported in this by an array of academics and liberal pundits throughout Europe. But they would always, without fail, capitulate to the status quo. Largely because they were afraid or unwilling to break with Brussels.

New Democracy didn’t have to do much to win the 2019 elections. Syriza’s four years in power had been a thoroughly disillusioning experience for much of the Greek electorate. Tsipras had promised an end to austerity and then spent four years delivering it. New Democracy at least had the advantage of honesty. Headed up by Kyriakos Mitsotakis, an arch technocrat and scion of the Greek political establishment, it promised the same austerity measures, only delivered more competently. Since its 2019 victory, New Democracy has effectively picked up where Syriza left off. It has continued to do the bidding of the Troika, just with less of the rhetorical friction.

And still Greece remains in the doldrums. It may technically have the fastest growing economy in the Eurozone, as trumpeted by the likes of the pro-EU Financial Times, but it’s starting from a very low base. Between 2008 and 2016, the Greek economy shrank by a quarter, with unemployment peaking at nearly 30 per cent. Greece isn’t surging ahead, as the Europhiles would have it, it’s slowly recovering from its own Great Depression. Today, it has one of the highest rates of people at risk of poverty in Europe. Real incomes have continued to fall, declining by 7.4 per cent in 2022 alone. And data show that one in two Greek households can barely get by on their monthly income. Indeed, the Greeks have more overdue bills than any other member of the Eurozone.

The legacy of the austerity years continues to bite hard. In February, 57 people were killed in a rail crash. Many have blamed this tragedy on the absence of investment in the once state-owned rail company, which was sold off to an Italian rail firm by Syriza in 2017.

The New Democracy government has also struggled with the ongoing migrant crisis, spiralling inflation and a spying scandal. (It emerged last year that Nikos Androulakis, leader of the centre-left Pasok party, had been under state surveillance.)

Yet despite the struggles of the New Democracy government, despite its continued adherence to the punishing demands of the EU, the ECB and the IMF, Syriza has made no progress at all in opposition. Quite the opposite. It has gone backwards in the past four years.

The most damaging legacy of the Syriza years is that they have left the Greek people demoralised. In the end, Syriza effectively told its voters that there is no alternative to the demands of the Troika. That stringent budget targets, mass privatisation and general impoverishment are the only possible future. That their votes changed nothing. And so, many have either accepted the rule of technocrats like Mitsotakis or have turned off politics completely. Others have lent protest votes to the far right. Nearly 50 per cent of the electorate didn’t bother to vote at the weekend.

This demoralisation is the legacy of an allegedly left-populist project that completely and utterly failed. That wanted to take on the European Union while clinging on to its structures. That called for courage but offered only capitulation. The Greek people deserve so much better.

Tim Black is a spiked columnist.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.