Long-read

The cancellation of classical music

The crusade against ‘whiteness’ is destroying culture.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

Until August 2020, Dona Vaughn had been the longtime artistic director of opera at the Manhattan School of Music. Her experience included singing, acting and directing on and off Broadway and on opera stages. The Manhattan School of Music’s 2019 production of Saverio Mercadante’s little-known opera buffa, I due Figaro, showed her influence in stunningly charismatic and witty student performances.

Vaughn was committed to championing minority musicians – so much so that she endowed a scholarship for them at her alma mater, Brevard College in North Carolina. ‘In all my years of teaching’, she said at the time, ‘I often have wished that more minority members were encouraged to pursue a music profession’. Besides the classics, she produced socially conscious contemporary works, giving the first professional staging, for example, at the Fort Worth Opera Festival of a feminist opera about a 17th-century nun.

The mob cares nothing for facts, though. On 17 June 2020, Vaughn was teaching a class via Zoom on musical theatre. An unidentified participant, whose name and image were blacked out, asked her, out of the blue, how she could justify having produced Franz Lehár’s allegedly racist operetta, Das Land des Lächelns (The Land of Smiles), several years earlier. (The racial sin, in this case, was allegedly against Asians.) Vaughn cut the questioner off for raising an issue irrelevant to the current discussion.

The fuse was lit. A Manhattan School of Music student petition was immediately forthcoming. Vaughn must be fired because she is a ‘danger to the arts community’, it thundered. The petition resurrected a meme from the time of the Lehár production: that Vaughn had cast a black singer as a butler, thus supposedly proving her racism. For good measure, the petition threw in unspecified ‘reports’ of ‘homophobic aggression and body shaming’. The petition quickly garnered 1,800 signatures. Phoney Instagram accounts under Vaughn’s name suddenly appeared on the web, containing fake inflammatory material

Vaughn’s colleagues, cowering from the mob, let her twist in the wind. Almost none came to her defence. Vaughn was fired and replaced by a black male.

The Manhattan School of Music administration apparently made no effort to speak with Vaughn’s former students, who would have rebutted the false charges against her. Howard Watkins is a black assistant conductor at the Metropolitan Opera and a faculty member at Juilliard; he has accompanied world-famous singers and conducted at some of the most prestigious venues in the industry. In a heartfelt character reference after she had been fired, he chronicled his history with Vaughn. In 1988, he was enrolled in the Lindemann Young Artist Development Programme at the Metropolitan Opera. Vaughn was the programme’s stage director and acting coach. Watkins wrote that Vaughn was responsible for many of his greatest experiences there. ‘Her classes provided all of us with specific tools towards improving our artistic growth and understanding… It is tremendously sad that the students of Manhattan School have been deprived of the opportunity of learning from someone with vast knowledge, the passionate desire to see them succeed and the integrity to say what must be said for them to grow.’

Bass-baritone LaMarcus Miller – also black – worked in Vaughn’s Opera Workshop and Opera Lab at the Manhattan School of Music in the early 2010s. She was a ‘pillar of integrity’ and the ‘epitome of a mentor’, he said. ‘I’ve only seen her be tremendously inclusive, while holding students accountable for their actions.’

Days after the firing, the anonymous petition instigator posted a follow-up:

‘Victory! Dona D Vaughn has been removed from her position at MSM. Thank you to everyone who supported this petition. The work is never over and I hope you all feel strengthened by this victory.’

The ‘hope’ is well-founded; on to the next takedown. As for Vaughn, she was in shock. ‘I do not have words to describe it. It’s guilt by allegation’, she said at the time.

Musicology in the dock

In recent years, another academic has also been fighting back against a similarly false allegation of racism. Timothy Jackson is a music theory professor at the University of North Texas. He specialises in the work of 20th-century Austrian music theorist Heinrich Schenker, who developed an influential system of analysis that identifies the most important elements of a musical phrase in order to explain the phrase’s emotional impact and its role within a work’s thematic development. Jackson is also the former head of the Centre for Schenkerian Studies and the former editor of the Journal of Schenkerian Studies.

In November 2019, Hunter College musicologist Philip Ewell gave a keynote address at the annual meeting of the Society for Music Theory, titled ‘Music Theory’s White Racial Frame’. Ewell argued that Schenker’s ranking of notes and harmonies within a composition is merely a stand-in for a white supremacist ranking of the races. The ‘white racial frame’ of Schenkerian analysis has kept blacks from becoming music theorists, Ewell maintained.

Jackson responded by putting out a call to members of the Society for Music Theory (including to Ewell) to contribute to a symposium in the Journal of Schenkerian Studies. The majority of the essays, published in July 2020, were critical, although some were supportive. But few stated the obvious: that to equate Schenker’s ranking of notes and harmonies with racial hierarchies is lunacy.

A hierarchy of keys and of harmonies within those keys is constitutive of Western tonal music. It has nothing to do with alleged racial hierarchy. Ewell’s position means that tonal music is itself racist. Every composer writing in a tonal idiom, including composers of colour, would be engaged in a racist enterprise. So would be anyone in any field of activity that recognises dominant and subdominant elements – whether art analysis, chemistry or engineering. Distinctions between gravitational, nuclear and electromagnetic forces would render our very universe a site of cosmic racism. Of course, the rhetorical slippery slope holds no fear for Ewell. There can never be too many examples of white supremacy.

Jackson’s response focussed on Ewell’s denunciations of Schenker as a proto-Nazi. Ewell had failed to mention Schenker’s outsider status as an Austrian Jew or his widow’s death in a concentration camp. Ewell’s silence on these matters, Jackson wrote, may be related to black anti-Semitism. Ewell has called for more rap repertoire in music curricula. Before acceding to that demand, Jackson advised, music departments should grapple with rap’s anti-Semitism and misogyny. The underrepresentation of blacks in music theory is due to the fact that few blacks ‘grow up in homes where classical music is profoundly valued’, Jackson concluded, before issuing a call to demolish ‘institutionalised racist barriers’.

The executive board of the Society for Music Theory responded to Jackson’s defence by accusing him of ‘replicating a culture of whiteness’. Jackson’s colleagues at the University of North Texas blasted him for publishing a symposium ‘replete with racial stereotyping and tropes’. Graduate students said that Jackson must be fired for his history of ‘particularly racist and unacceptable’ actions.

If Jackson made a mistake, it was to refute Ewell’s thesis on irrelevant biographical grounds and to deploy Ewell’s own ad hominem method against Ewell himself. Instead, he should have focussed on the absurdity of the harmony-race analogy itself.

Jackson was then removed from his editorship of the Journal of Schenkerian Studies. The chair of Jackson’s department informed him that the University of North Texas would be ceasing its financial and institutional support for the journal and for the Centre for Schenkerian Studies, essentially cancelling both institutions. Jackson is in the process of suing the university and the university’s regents for violating his First Amendment rights. Whatever the legal outcome, he will remain a pariah among colleagues and students.

Promoting mediocrity

The biggest victim in the racial attack on classical music is the music itself. Once the poison of identity politics is injected into a field, it can never recover its prelapsarian innocence. Every time an industry insider or critic disparages our greatest composers for being too white and too male, he gives neophytes, especially young people, another reason to close their ears to this legacy.

Seeking to make classical music politically acceptable, orchestras and conservatories are resurrecting lesser-known black composers from the past. (Other black composers, such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and William Grant Still, have been played on radio stations for decades now, and rightly so.) This enterprise would ordinarily call for celebration. The canon is performed to death. The more previously unfamiliar music we know, the greater our understanding of what it has meant to be human, since music traces the movement and yearnings of its composer’s soul. Rediscovering black contributions to classical music is particularly meaningful.

But the stated rationale for this resuscitation destroys its value. Every past composer now being presented on radio stations and in concert halls is said to have disappeared from public attention because of racism. That claim is, in most instances, fanciful.

Perhaps 98 per cent of all composers in the classical tradition are not listened to or even recognised today. Those forgotten artists were almost all white males. It is the sad fate of most composers to recede into obscurity, if they were even lucky enough to have had their music performed during their lifetimes. To charge history with racism for having allowed black composers to have also fallen into obscurity requires proof of overwhelming merit, strong enough to overcome the usual oblivion meted out to everyone else. That high burden of proof is rarely met.

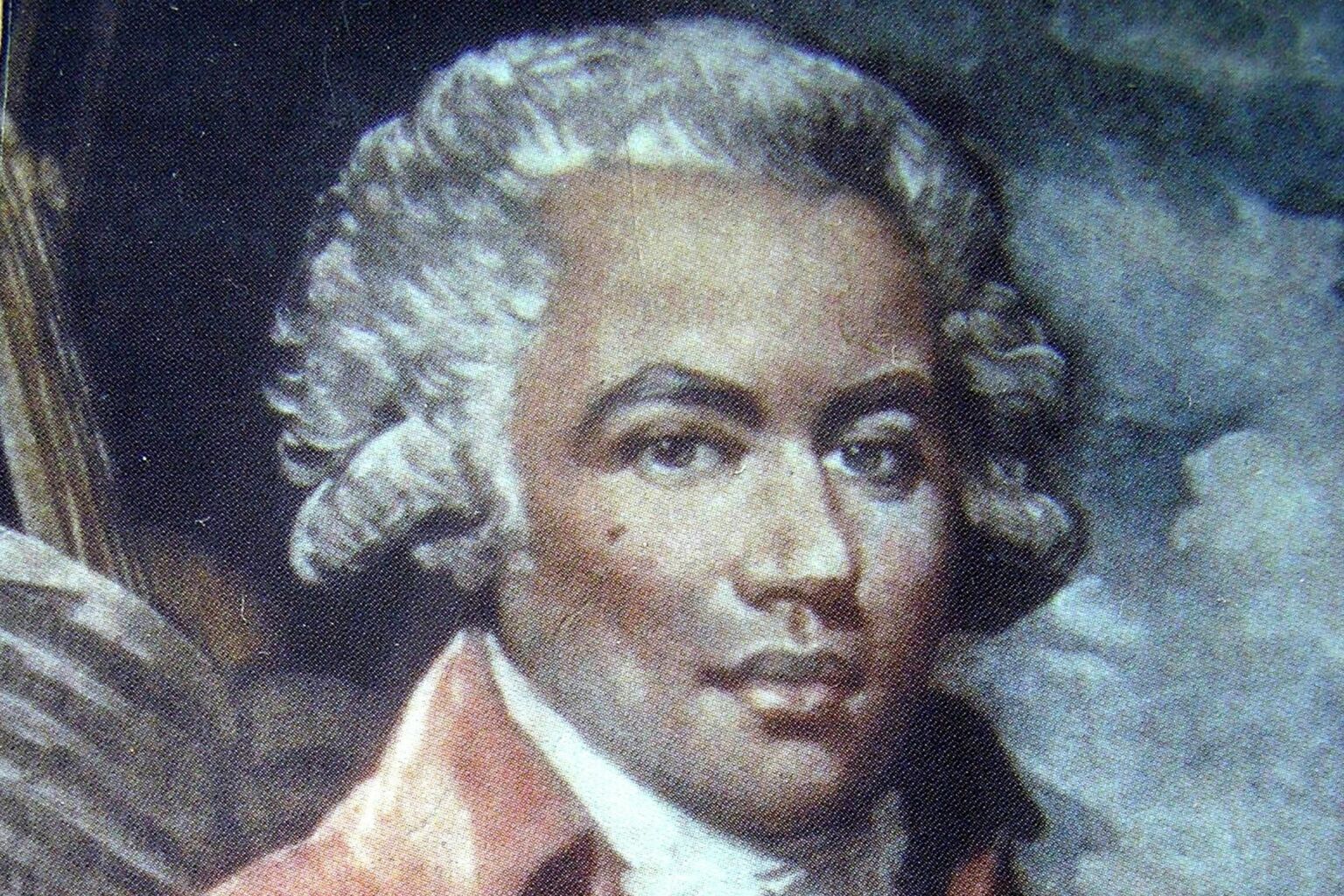

The composers enjoying the greatest prominence at the moment are Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799) and Florence Price (1887-1953). The hyperbole surrounding their works is astonishing.

Bologne was the son of a Guadeloupe plantation owner and a slave; he spent most of his life in Parisian court society. Throughout his twenties, Bologne enjoyed an annuity from his father’s estate, but he has not been cancelled for having profited from slave labour.

Bologne is commonly referred to today as the ‘black Mozart’. That comparison is laughable enough in its own right. Bologne is fluent in the classical style, with a pleasing capacity for forward momentum. His works are recognisable on the radio for their simple construction. But they possess none of the melodic gift and emotional depths that have led the world’s greatest composers to bow down before Mozart in dazed gratitude.

For some, even the ‘black Mozart’ label is insufficiently hagiographic. It is Mozart who should be called the ‘White Chevalier’, says Bill Barclay, a playwright-composer. This is preposterous. If Bologne were white, his oeuvre would remain marginal. Other contemporaries of Mozart, such as Antonio Rosetti, Joseph Martin Kraus and Josef Mysliveček, deserve revival before Bologne. It was not Bologne’s mixed-race status that consigned him to the same fate as nearly all his white colleagues, but his banality.

Florence Price has a major advantage over Bologne: she is of mixed ancestry and female, and thus intersectional. Price is most frequently compared with Antonín Dvořák. This, too, is overblown, though her American-vernacular style drew inspiration from the Czech composer, especially in its use of black spirituals. The Symphony No3 in C minor (from 1940), considered her masterwork, starts promisingly, with eerie, shifting chords emanating from the brass. There are moments of boisterous exaltation – above all, in one of her signature African ‘juba’ dances in the third movement – that incorporate early jazz harmonies. But the work is thematically inert and repetitive; its melodies, truncated. Frequent climaxes are generated artificially through cymbal clashes. Indeed, Price’s cymbal scoring makes Tchaikovsky’s fondness for the instrument look ascetic.

An influential pedagogue I have spoken to calls Price’s harmony, rhythm and materials ‘fourth-rate’. Long before the current Price boom, a prominent conductor searched for a piece of hers that he could, in good conscience, programme. He couldn’t find one, though he has happily conducted the works of other black composers, such as William Grant Still, Ulysses Kay and Alvin Singleton.

Sometimes the challenge proves too much even for the most willing boosters. The Financial Times, reviewing a Boston Symphony Orchestra concert from November 2020, admitted that Price’s String Quartet in G was ‘slight’. Not to worry, said the paper, it is ‘none the worse for that’.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiered Price’s First Symphony in 1933; it was favourably reviewed in the Chicago Daily News as ‘worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertory’. The WPA Orchestra of Detroit and several women’s orchestras played her compositions. If her works failed to find that lasting place in the repertory, it was not because of a racial lockout.

Ironically, the critics who champion Price now are ordinarily fierce advocates of the avant-garde. In Price, however, they elevate an aesthetically conservative style that would hold little interest for them if practised by a white male.

The hype being ladled on to recently revived black composers is not innocuous. The inflation is in the service of accusation and resentment. By blurring real distinctions in musical value, the racial boosters make it harder for new listeners to learn what makes this tradition monumental. Someone ignorant of classical music should not be told that there is no difference between Dvořák and Florence Price. A newcomer should start with the peaks, not the shallows. The wild applause that breaks out after a Price performance is due to its current political significance, not to its musical merits. Her works and those of other lesser-known composers deserve a grateful hearing. But the rapturous praise is condescending. In the meantime, works of more likely interest, such as operas by William Grant Still, remain a tantalising mystery.

As the lies about classical music accumulate, not one conductor, soloist or concertmaster has rebutted them. These influential performers know that Beethoven’s late piano sonatas and quartets are not about race, but about pushing beyond ordinary human experience into an unexplored universe of unsettling silences and space. They know that Schubert’s song cycles are not about race, but about yearning, disappointment and fleeting joy. They know that the Saint Matthew Passion is not about race, but about crushing sorrow that cries out in pain before finally finding consolation. To reduce everything in human experience to the ever more tedious theme of alleged racial oppression is narcissism. This music is not about you or me. It is about something grander than our narrow, petty selves. But narcissism, the signal characteristic of our time, is shrinking our cultural inheritance to a nullity.

These conductors and soloists are silent, though their knowledge has led them deep into that greatest of all human dramas: the evolution of expressive style. They can trace how the erotic languor of Chopin’s nocturnes and concerti became even more dangerously seductive in Brahms’s and Rachmaninoff’s piano works. They know that even one composer in this kaleidoscopic tradition contains more expressive depth than any individual can possibly fathom in a lifetime. These successful musicians have felt the terrifying anticipation – a moment without parallel in the repertoire – as a pianist sits quietly in front of the orchestral beast at the start of one of the great romantic piano concerti as waves of sound pour over him, or as he issues his own challenge first, whether a thunderclap or a whisper, and is answered in turn. The leaders have experienced this and yet they say nothing.

Classical music’s insider critics now throw in a class-bias count for good measure; these pseudo-Marxist accusations are as specious as the racism charge. To be sure, many 17th- and 18th-century composers had court patrons – and we should thank those nobles for underwriting such musical treasures. Pre-revolutionary opera seria legitimated absolute rule while also trying to nudge its royal attendees closer to Enlightenment ideals of tolerance and justice. The 18th-century Classical style is infused with nobility and grandeur; the French Baroque with the formality of Versailles. So what? With the arguable exception of opera seria, music written for wealthy patrons – whether Telemann’s Tafelmusik or Haydn’s symphonies – is not about class but about the abstract logic of musical expression. Western classical music has at times emerged from or elicited political passions. But those passions were usually associated with nationalist movements against monarchical regimes, exemplified by the frenzy that broke out in Pest in response to Berlioz’s orchestration of the anti-Habsburg ‘Rákóczi March’ in the mid-19th century. Most canonical composers were at odds, quietly or vociferously, with their respective governments.

The present-day scourges impugn concert protocols as a classist means of excluding a ‘diverse’ audience. But it was the bearers of inherited privilege during the ancien régime who treated music as a backdrop to be gambled and flirted through. It was the non-aristocratic classes who started attending to music with silent devotion, as it became more complex and demanding in the 19th century. As Timothy Jackson wrote in his article for the Schenker symposium, his maternal and paternal grandparents, impoverished refugees from Central and Eastern Europe, bought his mother and his father a cheap violin and a dilapidated piano during the Great Depression and scraped together enough money to pay for lessons. His working-class parents had done hard menial labour all their lives, but they heard classical music as a ‘call from another world, divine, mysteriously exalted, pointing to a higher plane of existence’.

Today’s warriors against ‘classism’ would presumably accuse José Antonio Abreu, a Venezuelan socialist economist, of being an unwitting tool of white ‘patriarchal power’, to use the BBC Music Magazine’s term for the canon. Abreu founded El Sistema, a programme of free classical-music training for barrio children in Caracas, in the belief that playing Bach, Schubert and Brahms would help deliver them from poverty and crime into a better world. El Sistema, Abreu said in 2008, was meant to ‘reveal to our children the beauty of music [so that] music shall reveal to our children the beauty of life’. Philip Ewell can sneer at Beethoven as, at best, ‘above average’. The BBC Music Magazine can snark that ‘greatness’ is a ‘manufactured quality’ designed to ‘sell scores of “greatness” to as many people as possible’. The graduates of El Sistema know better. Gustavo Dudamel, conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and El Sistema’s most famous product, said in 2011 that Beethoven is ‘not just the reference point of classical music; he is the master of us all.’ Beethoven’s Seventh is ‘happiness. It’s the only word that I find perfect for this music.’

A cultural betrayal

Though the keepers of our tradition surely know that classical music is a priceless inheritance, having devoted their lives to it, fear paralyses them as that legacy goes down. I have reached out to conductors, composers and company managers, but they have all decided to keep silent.

Perhaps they think that the racial assault on classical music is not worth taking seriously. Emanuel Ax, who did go on the record, laughed good-naturedly when told of Ewell’s Beethoven evaluation. ‘That is a wonderful quote’, he said. ‘This movement is not a danger to anyone.’ Ax is wrong. One need only look at the syllabi in literature departments today which, compared with those from 40 years ago, show the devastation that the unopposed march of identity politics wreaks on the transmission of greatness.

Other music professionals understand the danger. One educator warns: ‘If conservatories start admitting by race and ethnicity, close them down. As soon as standards are modified, the game is over. Mediocrity is like carbon monoxide: you can’t see it or smell it, but one day, you’re dead.’ Woke music administrators are relativising excellence as a white Western concept. Mention ‘quality’ in a meeting of performing-arts managers and you may be accused of ‘sending the wrong message’.

Some Juilliard professors have taken early retirement rather than risk conflict with the identity-obsessed mob. The striving for excellence is now secondary, Juilliard violin professor Earl Carlyss told me. ‘It is terrifying when politics takes precedence over quality.’

Conventions of scholarship are under attack as well. The distinguishing feature of Western classical music, which allowed an unparalleled transformation of style over seven centuries, is that it is written down, unlike most other world music. Notation allows us, miraculously, to hear what people were playing in the 15th century. But music departments are under pressure to eliminate the requirement that students can read scores, since such a requirement is purportedly exclusionary. Anti-racist musicologists are jettisoning another basic norm: source documentation. New York University musicologist Matthew Morrison scoffs at ‘Western (colonial) notions of “documentation”’. as he put it in a November 2020 tweet. He said that he doesn’t ‘put everything on paper. Some stuff is meant to be kept and transferred orally (and ritually).’ In other words, ask Morrison for his written sources and you may be accused of racism. It is a ‘colonial impulse’ to ‘desire to… have access to everything’, Morrison warns fellow academics and potential fact-checkers.

Morrison is no fringe character. He has held fellowships at Harvard, King’s College London, the American Musicological Society, the Mellon Foundation, the Library of Congress and the Tanglewood Music Centre. He has served as editor-in-chief of Current Musicology. And he represents the future.

The betrayal of the music guardians is not unique. Other individuals entrusted with preserving Western civilisation are abdicating their responsibility, too, either actively colluding with the forces of hate or passively allowing those forces to conquer their field.

The National Archives and Records Administration, founded to preserve the US’s historical records, declared itself guilty of systemic racism in April 2021. The Archivist’s Task Force on Racism, which produced the report, denounced the Capitol Rotunda in Washington, DC for lauding the ‘wealthy white men’ who participated in the nation’s founding, while ‘marginalising BIPOC, women and other communities’. Task force members included the directors of the John F Kennedy Presidential Library and the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library.

Every humanities subject is being hollowed out with similar charges. Under the logic of the current moment, any tradition that comes out of Europe is racist because its contributors will have been overwhelmingly white. It matters not that the demographics of Europe until the past 50 years made that racial composition inevitable. Balinese gamelan music, the Chinese opera, Indian classical music and the Nigerian talking drum have been as racially monolithic, without falling afoul of the diversity monitors. Only Western civilisation is under attack for its traditional racial homogeneity.

The poisoning of classical music is heartbreaking enough. But unless more people fight back and defend our inheritance, we are going to cancel an entire culture.

Heather Mac Donald is a New York Times bestselling author and Thomas W Smith fellow at the Manhattan Institute.

The above is an edited extract from Heather’s new book, When Race Trumps Merit: How the Pursuit of Equity Sacrifices Excellence, Destroys Beauty and Threatens Lives, published by DW Books. (Buy this book from Amazon (UK).)

Pictures by: Getty

With the exception of the first picture, by Ajay Suresh, published under a Creative Commons license.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.