We can’t let the race lobby hijack the Covid inquiry

The Covid pandemic had nothing to do with ‘structural racism’.

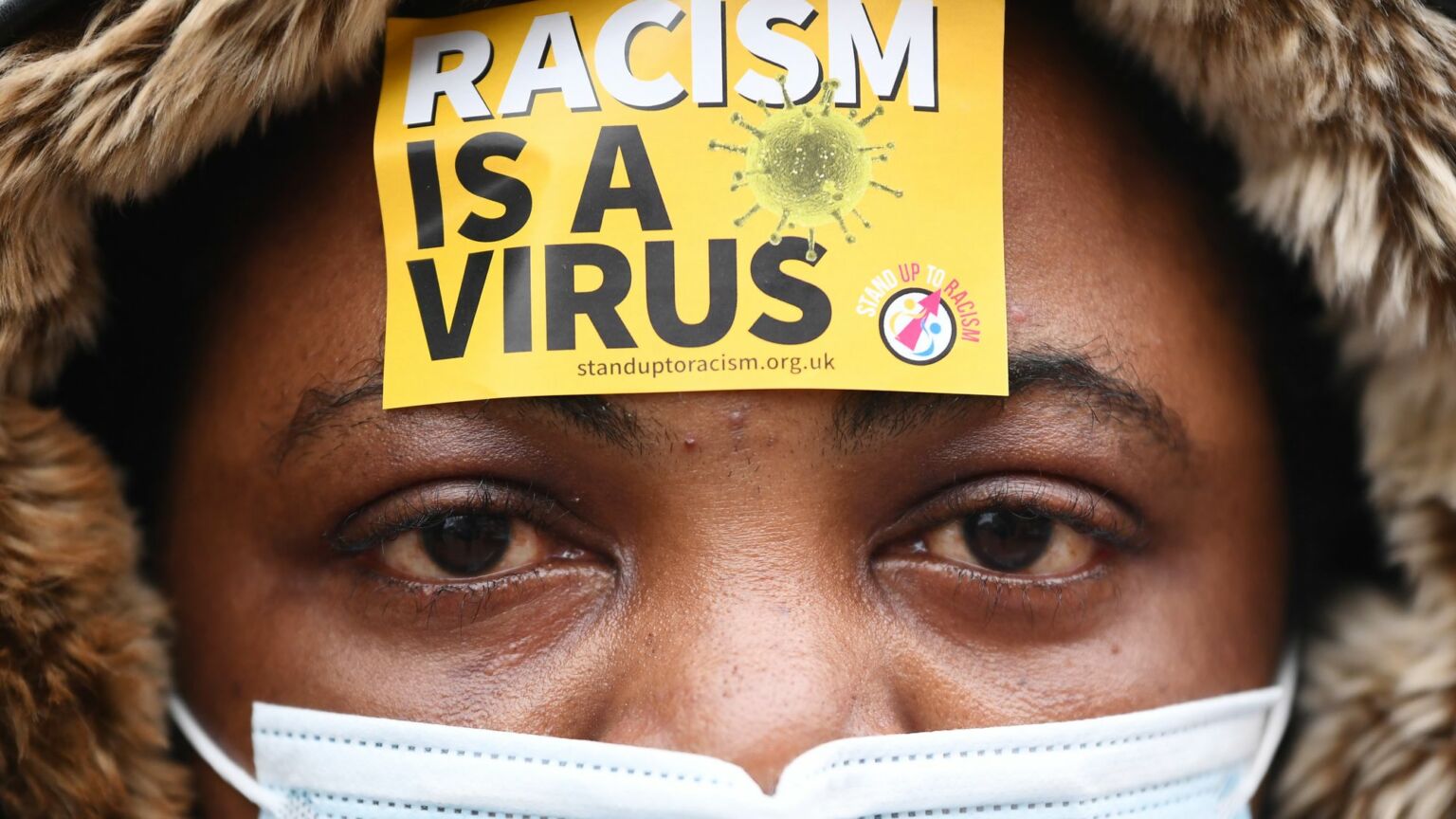

Three years on from when Covid-19 first struck the UK, some are continuing to use the pandemic to peddle a divisive identity politics.

This week, campaign groups have written a public letter to Baroness Hallett, the chairwoman of the independent public inquiry into the pandemic. Co-authored by race-equality think tank Runnymede Trust and pressure group Covid-19 Bereaved Families for Justice, and signed by 26 other organisations, the letter calls for racism to be treated ‘as a key issue’ at every stage of the investigation. This demand is extremely unhelpful. Placing race at the heart of the Covid inquiry will only obscure the truth.

It is true that in the earlier stages of the pandemic, the Covid-related mortality rate was higher among some black and Asian groups than among the white population. The risk was especially high for Bangladeshi, black Caribbean and Pakistani ethnic groups. Thankfully, last week, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) revealed that people from ethnic-minority backgrounds are now no longer more likely to die of Covid.

Ever since 2020, some have been determined to fold the pandemic into an identitarian narrative. London mayor Sadiq Khan even felt compelled to describe the disproportionate impact of Covid on ethnic-minority Britons as an ‘injustice’ caused by ‘structural racism’. Khan’s view was then echoed by a Labour Party review into the disparities in Covid outcomes. It concluded that Covid had ‘thrived’ in ‘BAME communities’ because of ‘the devastating impact of structural racism’.

Former shadow home secretary Diane Abbott went further, ascribing these Covid deaths to ‘a form of violence’ – caused, in her telling, by a racism that could be traced right back to the days of empire.

Blaming the disparities on racism is incredibly simplistic, however. It ignores the social, economic, geographical, lifestyle and genetic factors that are likely to have played a far more significant role.

Housing, for instance, clearly played a major role. Early on in the pandemic, overcrowding and multigenerational living exacerbated the spread of the virus among some groups. In England, just two per cent of white British people live in overcrowded housing. This figure rises to seven per cent, 16 per cent and 24 per cent for people of Indian, Black African and Bangladeshi origin respectively.

Meanwhile, cultural and language barriers prevented the absorption of public-health advice among harder-to-reach social groups. This problem cuts across racial lines. For instance, a comprehensive survey found that non-British white minorities were significantly less likely than white Britons to correctly identify core Covid-19 symptoms and to self-isolate accordingly. A notable portion of these were likely to be recent arrivals from EU countries, such as Poland, Romania and Bulgaria.

We also shouldn’t ignore Britain’s white Gypsy and Traveller communities. Despite their relatively youthful population, they did not fare well at all during the pandemic. Many live in confined households and are disproportionately affected by a lack of basic amenities, including running water, adequate sanitation and waste-management facilities. Concepts like ‘structural racism’ do not go very far in explaining why these underprivileged white communities suffered disproportionately at the hands of Covid.

It is true that the pandemic taught the UK some harsh lessons. It showed the need for better-communicated health guidance, tailored to the needs of all British citizens. And it revealed how marginalised communities of all races tend to be the most distrustful of advice coming from the government. What the pandemic did not reveal, however, is any evidence of ‘structural racism’ at the heart of national life.

The Covid inquiry must resist the temptations of identity politics. If it focusses on race, it is bound to learn the wrong lessons.

Rakib Ehsan is the author of the forthcoming book, Beyond Grievance, which is available to pre-order on Amazon.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.