The retreat from globalism

People don’t want to be squelched by big business or big government.

Want unlimited, ad-free access? Become a spiked supporter.

In the wake of liberal globalism’s failings, a nationalist tide is rising today, not only in China and Russia but also throughout the West. It is a dynamic eerily similar to 100 years ago, when war, pandemic and economic insecurity brought national tensions to the surface. Yet today’s undoubted turn against globalism need not herald a return to the dark days of aggressive nationalism. Instead, we are seeing the rise of a new community-based and self-governing model of localism.

This new localism counteracts some of the worst aspects of globalism – homogeneity, deindustrialisation and ever-growing class divides – while eschewing the authoritarian tendencies often associated with nationalistic fervour. It essentially seeks to replace, where possible, mass institutions and production with local entrepreneurship and competition.

This approach has demonstrated remarkable appeal. The promising evolution of technologies like remote work and 3D printing is already creating opportunities to enhance local economies. In the US, strong majorities trust local governments, compared to the more than half who lack trust in Washington, notes Gallup. Big companies, banks and media receive low marks from the public, but small businesses continue to enjoy widespread support across party lines.

This is not merely an American phenomenon. In France there have been consistent protests against globalisation for decades. Poland and the rest of eastern Europe, recovering from decades of central control and imperial edicts from Moscow, have also favoured localism. There is also pushback against federal encroachment in Canada, while the UK’s turn against globalism was best exemplified by its withdrawal from the EU.

The movement against globalism constitutes an alternative to increasingly intrusive government: such as in Europe, where the unelected EU bureaucracy seeks ever-expanding powers, and in North America and Australia, where national bureaucracies work to undermine traditionally vibrant local communities. It also has strong connections to populism, particularly in Europe. Its base, small business, tends to tilt to the right in most countries, including the US.

Yet the new localism is not fundamentally a question of left vs right. It is about sustaining local economies and self-governing institutions. According to Kevin Albertson, professor of economics at Manchester University, in politics today it often seems that the only choice on offer is between ‘big state or big business’. Faced with this unenviable dilemma, he argues, the ‘only viable alternative’ is localism – that is, ‘small state and small business’.

Essentially, localism looks to humanise the economy. Whereas global or national conglomerates respond largely to capital flows, local businesses rely heavily on networks of customers and suppliers. In the food industry, many start off as home-based businesses, and then become food trucks. Some evolve into modest restaurants, and occasionally open numerous locations, usually in the same region. These offer an alternative to the sameness of chain stores, at a time when many once ubiquitous traditional venues – pubs in London, bistros in Paris, as well as kosher delicatessens and Greek diners in places like New York – have declined.

Over the past few years, the supply-chain issues and the general disruption of the pandemic have caused a surge of consumers seeking out local products, with around four in five feeling strongly about championing local produce. This trend is apparent in places as diverse as China, Italy and South Korea. In the US, this could be seen even before the lockdowns, with the number of people shopping at small businesses instead of department stores increasing by three million in 2019.

In denser urban areas, the appeal of localism can be seen in the shift of economic activity towards local neighbourhoods and away from downtown hubs. In New York, for example, the decline in office workers has meant that more talented people, many working remotely, can cluster in urban neighbourhoods such as Brooklyn’s Park Slope, Carroll Gardens and Brooklyn Heights. Brooklyn’s real-estate market appears robust, even as other parts of New York City face profound trials. Between 2019 and 2021, over 1,200 new enterprises opened in Brooklyn, while Manhattan lost over 5,000 businesses.

Many small businesses are still suffering from the aftershocks of labour shortages and supply-chain blockages since lockdown. Yet far from destroying local businesses, the new conditions have generated a rise in new business formations in the US, with up to 4.4million applications in 2020 compared to roughly 3.5million in 2019. In 2021, new business formations were up by 44 per cent from before the pandemic. The Economic Innovation Group estimates that new business formations for 2022 will set a historic record.

The epicentre of this entrepreneurial surge lies in the rapidly growing urban periphery, particularly in the Sun Belt. Between 2010 and 2020, suburbs and exurbs accounted for about 90 per cent of all US metropolitan growth. Between 2020 and 2021, census data show movement out of major metropolitan areas more than tripled across America, driven by factors such as the ability of some professionals to work anywhere, a desire to flee densely populated areas for health reasons and, for some, a new focus on quality of life. A shift to the periphery is also evident in the UK,Australia, Canada, France and across Europe.

The shift of a younger workforce headed to other states and communities provides new economic stimulus to the receiving locations. One study from the University of Chicago suggests as many as 34 per cent of American workers could do their jobs remotely, an attitude widely adopted by the new wave of startups. Many workers from the ‘new economy’ of business services, business management and even tech jobs are moving away from traditional hotbeds like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and San Francisco to places like Austin, Dallas, Salt Lake City and Raleigh-Durham. Over the next decade, according to a Cyberstates survey, Utah, Arizona, Texas, Colorado and Nevada are expected to have the biggest tech growth, well ahead of California, New York or Massachusetts.

New movers might find the cultural infrastructure in these places to be poorly developed and monotonous. For someone used to the streets of London, New York or San Francisco, the lack of restaurants, artistic spaces and places to stroll could prove maddening. Yet some of these increasingly diverse new peripheral communities – the Woodlands outside Houston, Irvine in Orange County and New Albany outside Columbus – are replicating cities by enhancing their main streets or even creating brand new downtowns. There has also been a rush to build community centres and cultural institutions like theatres.

One key challenge facing these new communities lies in the uniformity of retail offerings. Most of the new downtowns today are filled with chain stores. Even if built outside and in brick, these are essentially malls. But there’s now a growing counter-movement toward authenticity and local novelty – one that reflects the shifts in population that are taking place on the suburban fringe. This trend is visible in the proliferation of farmer’s markets in the US, whose numbers have exploded from roughly 1,750 in 1994 to over 8,700 in 2019.

California-based developer Shaheen Sadeghi attributes much of this shift to the changes in who lives in suburbia, which is increasingly home, notably, to educated millennials, minorities and educated professionals. These consumers often feel alienated by the traditional mall experience, notes Sadeghi. People will pay more, and enjoy things more, he suggests, if they know the provider and identify it with their local community.

In the ‘anti-malls’ Sadeghi builds, chains are not allowed, and most businesses are owned by local people. Many of the small artisanal firms and food places that Sadeghi promotes have roots in ethnic communities that now proliferate in the suburbs – between 2000 and 2019, over 95 per cent of all growth in US suburbs came from immigrants and minorities. These groups are also settling increasingly in sprawling Sun Belt regions and even Rust Belt cities, particularly those with relatively low housing costs. Last year, a list of new Vietnamese restaurants in the New York Times focussed overwhelmingly on Sun Belt and suburban locales, where ethnic fast-food formats have become increasingly popular.

Today, you often find craft-oriented businesses in unexpected places. Tucson, Arizona is a long way from Brooklyn and its world-famous bagels. But it is home to Barrio Bread, founded by Tom Guerra in 2016 in his home. Guerra bakes a range of home-grown breads that draw huge crowds.

These new establishments manage to compete with chains with multi-million dollar marketing budgets through word-of-mouth advertising and internet buzz. They also benefit from personal ties with local suppliers. Among food businesses, the pandemic sparked a greater desire for supply-chain resilience offered by local producers, as notes Jason Lusk, head of agricultural economics at Indiana’s Purdue University.

Many food businesses have found ways to link up with family-owned farms – 96 per cent of all agricultural establishments – as a way to guarantee supply and provide an edge in quality. At a time when large retailers like Walmart are getting harsher with suppliers, ranchers now often seek to sell directly to restaurants and consumers. Wheat and rye growers market directly to the 2,000-member Bread Bakers Guild. Many of these small farms are also quite new. According to US government data, there are now 456,000 ‘beginning farmers’, defined as those with less than a decade’s experience.

Even in highly urbanised areas, small-scale farms can supply nearby consumers and restaurants, as notes AG Kawamura, a third-generation farmer from Orange County, California. Kawamura farms small vegetable plots in selected spots amid southern California’s urban sprawl. He and others are working on the development of new fertilisers that can retain productivity while reducing toxicity, a key concern of urban consumers.

A similar transformation is possible for manufactured goods. Often seen as a force for homogenisation, technology can also promote greater diversity in manufacturing. Ned Hill, professor of economic development at Ohio State University, suggests that 3D printing can allow firms to produce locally, and in smaller batches, what was once mass-produced and imported over large distances. Technology groups like America Makes are already training a 3D-printing workforce that can localise manufacturing.

Today, after the decades-long rush to centralise power in large corporate or state institutions, we stand at the brink of a great localist counter-movement.

This will not look the same everywhere. There’s often little common ground between ultra-progressive hipster magnets like Portland and those in conservative eastern Oregon, both of which have embraced localism in their own ways. No one should hope to harmonise California with Mississippi, or to force denizens of English market towns or French villages to behave like Londoners or Parisians. We should allow certain choices to be made locally, within constitutional boundaries.

Although such a notion might be considered conservative, it has strong roots on the left, too. In the early 20th century, progressive justice Louis Brandeis dubbed the institutions of local government ‘laboratories of democracy’. President Bill Clinton later endorsed this notion, arguing that in ‘a country as complex and diverse as ours’, decentralised decision-making only made sense.

Today, localisation still garners some support from the left. Some correctly see increasingly prevalent global firms as drivers of inequality and engines of displacement. Others, such as Yale Law professor Heather Gerken, make the case that progressive social causes like racial integration, gay marriage and marijuana legalisation have generally tended to be adopted at a local level first, before spreading to other areas. Gerken argues that it is necessary for cities and states to have certain powers so that local ‘cities on a hill’ of social reform can be allowed to flourish and lead by example.

Sadly, the Biden administration has become enamoured with issuing executive orders and is attempting to run America’s communities from Washington. This may not prove popular, even with many Democratic constituencies. Millennials, largely liberal on issues such as immigration and gay marriage, are also strongly in favour of community-based, local solutions to key problems. Socially conscious though they may be, they do not necessarily favour the top-down governance structures embraced by earlier generations of progressives. One National Journal poll found that less than a third of millennials favour federal solutions over locally based ones. Most are far less trusting of major national institutions than their Gen X predecessors.

Localism offers an alternative to two forces that are undermining liberal capitalism: ever-expanding central government and the largely unregulated power of key corporate institutions. By concentrating authority in a few hands, both suppress differences and squelch grassroots competition. This undermines the moral basis of capitalism, which is essentially about competition and aspiration. As Lenin understood, the real enemy of statist collectivism comes not from large economic units but from ‘small-scale commercial production’ – it is this, he argued, that ‘every moment of every day, [gives] birth spontaneously to capitalism and the bourgeoisie’.

Throughout history, small business and dispersed ownership of the means of production have proven critical to democratic and social progress – from the early days of the Roman Republic through to the rise of the Netherlands and Great Britain. Local enterprise has also long been a critical source of America’s dynamism. As Alexis de Tocqueville observed in Democracy in America in the 19th century, the ‘habits of self-government’ are acquired through civic association driven partly by local businesses.

Today, it is still in local venues that the claims of democratic citizenship are most keenly felt. By restoring dynamic local economies and the uniqueness of places, and by reviving competition and creating opportunities at the grassroots level, the new localism provides a welcome buffer both to the progressive nanny-state dream and the conformist, soul-crushing course of unrestrained global capitalism. Long may it continue.

Joel Kotkin is a spiked columnist, the presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute. His latest book, The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, is out now. Follow him on Twitter: @joelkotkin

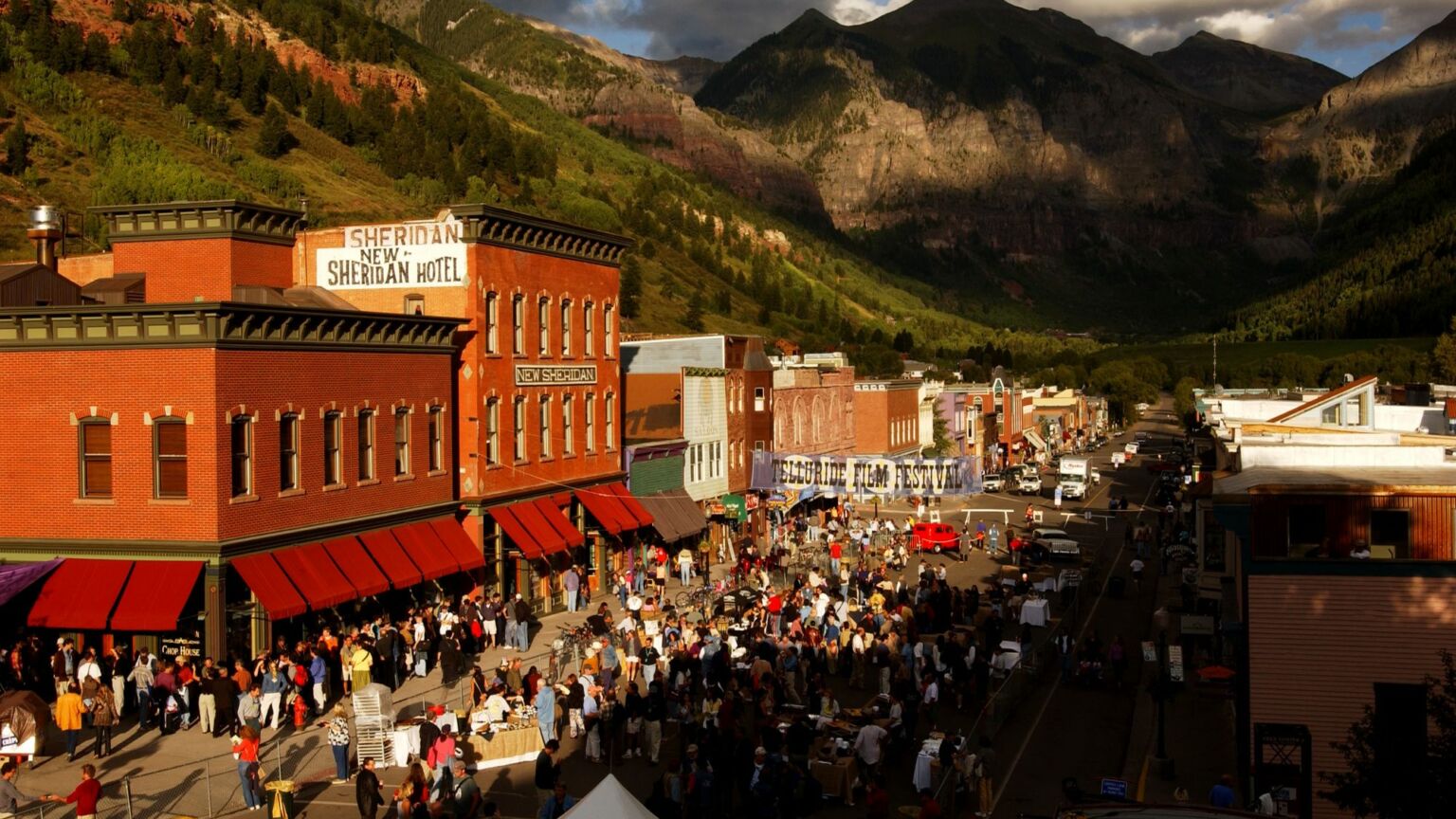

Picture by: Getty.

You’ve hit your monthly free article limit.

Support spiked and get unlimited access.

Support spiked and get unlimited access

spiked is funded by readers like you. Only 0.1% of regular readers currently support us. If just 1% did, we could grow our team and step up the fight for free speech and democracy.

Become a spiked supporter and enjoy unlimited, ad-free access, bonus content and exclusive events – while helping to keep independent journalism alive.

Monthly support makes the biggest difference. Thank you.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.