The making of Nineteen Eighty-Four

A new manuscript edition allows us to see Orwell’s masterpiece anew.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

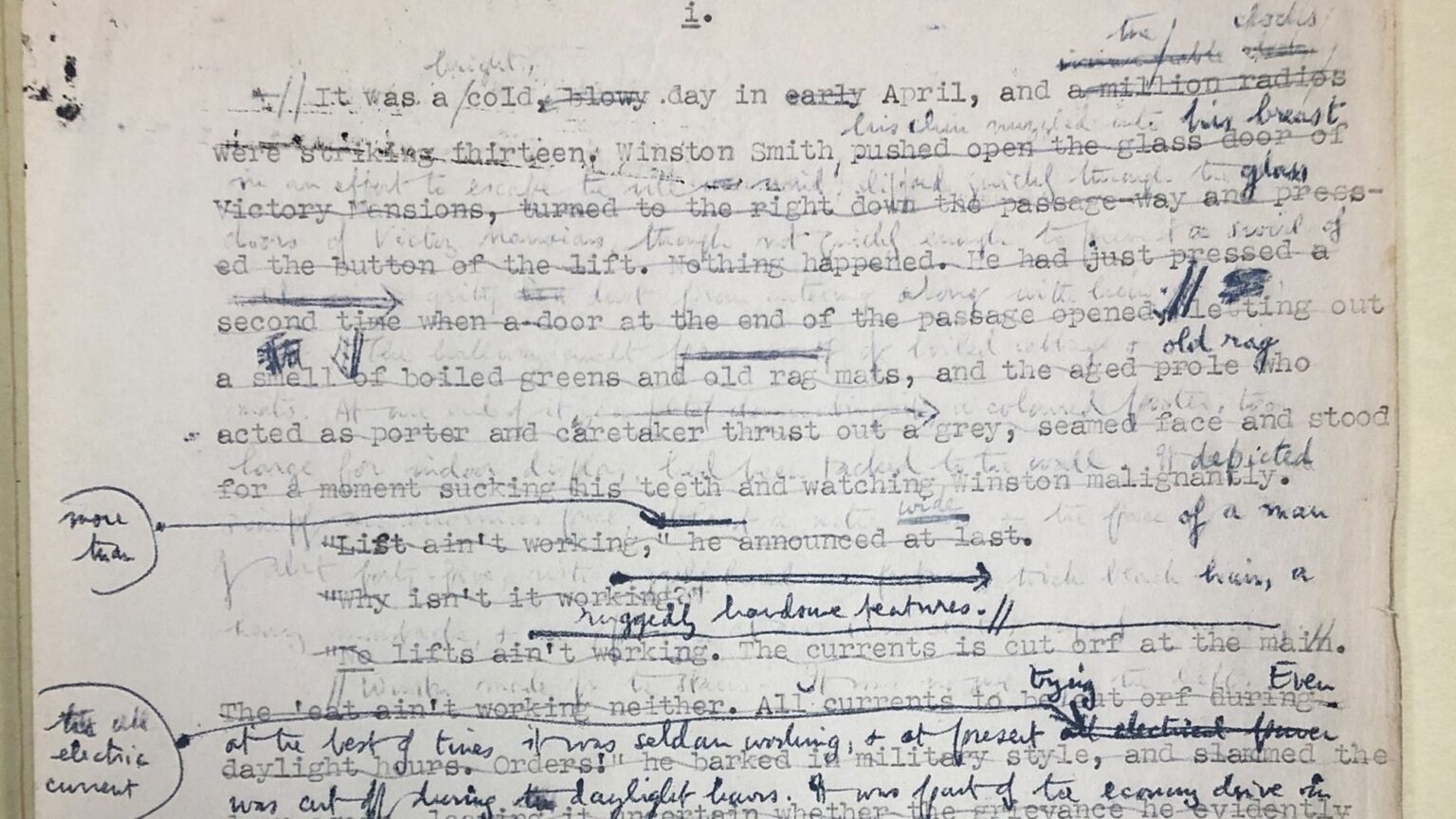

‘The thing that he was about to do was to open a diary’, writes Orwell in Nineteen Eighty-Four. ‘This was not illegal (nothing was illegal, since there were no longer any laws), but if detected it was reasonably certain that it would be punished by death, or at least by 25 years in a forced-labour camp.’ That is what it is like to hold this brand new, manuscript edition of Nineteen Eighty-Four in your hands. You feel as if you are doing something you shouldn’t. You get to see Orwell’s own handwriting. His revisions and reworkings. His mind in motion. It is a clandestine and intimate experience, like having a glimpse into Winston Smith’s diary.

Published by SP Books, this is Nineteen Eighty-Four as you’ve never seen it before. It reproduces, in colour facsimile, the 197 surviving pages of Orwell’s manuscript, held by the John Hay Library at Brown University, Rhode Island. We see Orwell’s work in fountain pen and ballpoint (complete with ink blots), as well as 14 typewritten sides. We are even given his doodles and pen tests. Readers will remember how Winston also marvels at the beauty of the paper and binding of a blank book he buys from a junk shop.

This edition contains what amounts to 44 per cent of the text of the published novel. It is in a jumbled state, with pages missing and drastic changes made. There are many crossings out and additions. The handwriting can be a little tricky to decipher – Orwell had a habit of using cursive joining lines between words and using abbreviations. Added to that, the script can be somewhat crabbed, especially where Orwell adds text between existing lines. With a little patience, though, the reader can adjust to Orwell’s writing, especially if familiar with the text, and glimpse this most familiar of novels anew.

This version includes an introduction by Orwell scholar DJ Taylor. He tells us that although Orwell usually wrote quickly, he took five years to complete Nineteen Eighty-Four. Taylor details the difficult conditions that explain the novel’s long gestation. The death of Orwell’s first wife in 1945, the effort of raising their young son alone and the toll of tuberculosis all slowed work and drained the author’s energy (tuberculosis would kill him in 1950, only months after the novel’s publication). There are indications that Orwell let the book go to publication even though he thought it was not properly finished.

Looking at this draft, we can see Orwell revising heavily as he wrote. Some revisions are minor, such as Trotsky-figure Goldstein’s description of the workings of the Party and his description of the geopolitics of Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia. Other changes are more significant. Here, in the propaganda film described by Winston at the start of his diary, there is a graphic passage about the lynching of a pregnant black woman. Orwell seems to have cut these lines on grounds of decency. He also reduced the references to race overall, perhaps uncomfortable about the implications of speaking so generally about groups and types. Orwell’s background as a policeman in Burma no doubt made him sensitive to racial issues.

Another part cut from the final manuscript describes a meeting between Winston and Julia in public. It implies that Winston had his doubts about whether Julia truly loved him or was acting to ensnare him. In the final version, however, it is left unclear whether or not Julia betrays Winston in advance of their capture. Winston is shown to trust Julia.

It could be that she always intended to entrap him. But the usual interpretation is that Julia genuinely does love Winston. The highly regarded film version, for instance, starring John Hurt and Richard Burton and released in 1984, seems to take the view that the relationship is genuine. But here, in the manuscript version, a more cynical and depressing reading emerges. Winston, deluding himself about Julia, has been set up by the Thought Police. She appears to be an agent sent to seduce him and expose his political incorrectness.

One also notices a host of minor changes, allowing the prose to flow more naturally or to make the language more measured. It reveals the depth of Orwell’s craft. In Goldstein’s treatise on the forever wars between the superpowers, he explains how they are about destruction of resources rather than military victory. ‘It is like the battles between certain ruminant animals whose horns are set at such an angle that they are incapable of hurting one another.’ This original version has ‘stags’; the substitution in the finished text makes Goldstein’s text seem less vivid, and more fitting to the deadening style of Newspeak.

Whole chunks of story are missing or out of order in the facsimile: clearly, much was written in drafts that have subsequently been lost. It seems Orwell rarely kept his manuscripts – no original drafts for his other books survive. Taylor believes that a careful writer such as Orwell would have revised and adjusted Nineteen Eighty-Four further still, if his life expectancy had been longer.

Nevertheless, what remains of Orwell’s manuscripts makes for a genuinely illuminating reading experience. It allows us to look over Orwell’s shoulder as he composed what is surely the most influential British novel of the 20th century.

Alexander Adams is an artist, art critic and author. His books Culture War and Iconoclasm are published by Societas.

1984, the manuscript by George Orwell, is published by SP Books. Order it here.

Picture by: Brown University Library.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.