Long-read

From the Cuban Missile Crisis to Ukraine

What the stand-off of 60 years ago tells us about the threat of nuclear war today.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

It has been 60 years since the start of the Cuban Missile Crisis. From 16 to 29 October 1962, the superpowers of the US and the Soviet Union threatened each other with nuclear weapons over a narrow stretch of the Caribbean Sea, and for a tense fortnight many believed the world was on the brink of destruction.

A 60th anniversary might not normally attract too much attention. However, in one of those tricks of history, the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis coincides with loud talk of a possible nuclear escalation in Russia’s bloody war in Ukraine.

The coincidence prompted US president Joe Biden to raise the temperature further, by declaring that Russian president Vladimir Putin’s threat to use nuclear weapons posed the biggest danger for 60 years: ‘We have not faced the prospect of Armageddon since [President John F] Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis.’ Other American officials have backed Biden’s comparison and gone further still. One former assistant secretary for defence says, ‘This crisis is more dangerous than the Cuban Missile Crisis’, noting that the 1962 crisis did not occur in the middle of a ‘hot war’ like the current conflict in Ukraine.

Such scary comparisons seem easy to make. But how useful are they in understanding the realities of international relations and the threat of nuclear war, then and now?

First, a quick reminder of what happened 60 years ago. The Cuban Missile Crisis occurred at the height of the Cold War, the global stand-off between the US, as leader of the Western world, and the Soviet Union, dominant power in the Communist bloc. Though a nuclear superpower, the Soviet Union’s missile arsenal was far less powerful than America’s. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev sought to address this imbalance by siting missiles on Cuba, just off the coast of Florida. His allies in the Communist regime of Fidel Castro were also keen to host the nukes (along with the Soviet troops and weaponry already on the island), after the failed US-backed invasion of Cuba’s Bay of Pigs in 1961.

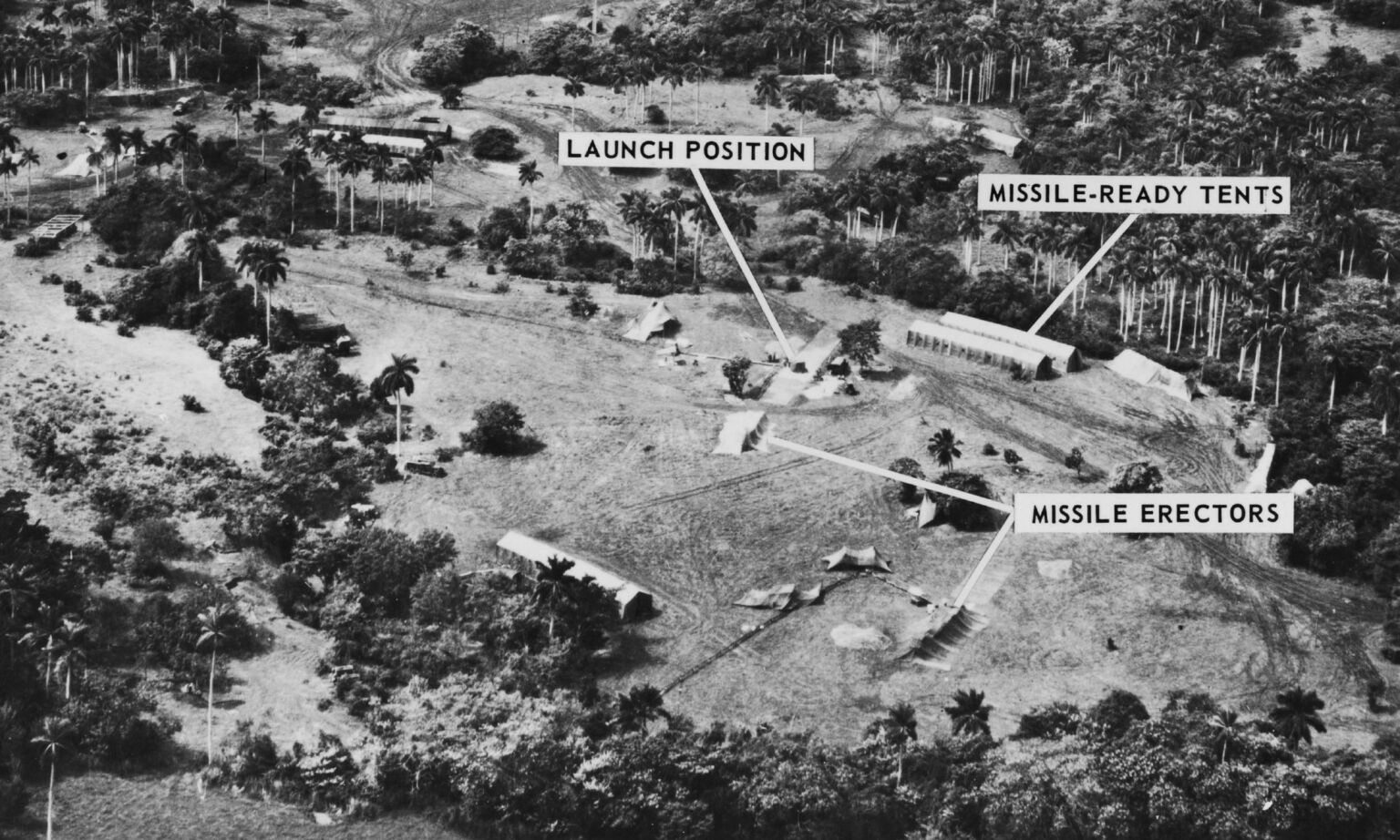

The crisis proper began in mid-October 1962, after American surveillance planes confirmed the presence of Soviet nuclear missile facilities on Cuba. Tensions rose over the next fortnight with warlike talk on both sides. On 22 October, President Kennedy gave an address, broadcast nationwide on every major TV network, announcing the discovery of the missiles. Kennedy told the American people and the world that, ‘It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union’. The threat of nuclear world war was on the table.

The US imposed a naval ‘quarantine’ around Cuba to prevent the arrival of missiles, and an American U-2 spy plane was shot down over Cuba, with the pilot killed. After that incident, the US president’s brother and attorney general, Robert Kennedy, reportedly told the Soviet ambassador that, ‘You have drawn first blood… [T]he president had decided against advice… not to respond militarily to that attack’; but the Soviets ‘should know that if another plane was shot at’, the Americans would ‘take out’ all Soviet missiles on Cuba, ‘[a]nd that would almost surely be followed by an invasion’.

Khrushchev blinked and a deal was done, whereby the Soviets agreed not to site nukes on Cuba and America agreed to end the quarantine and not to invade the island. President Kennedy also agreed to remove some near-obsolete US missiles from Turkey, though this was not made public as part of the deal. The crisis formally ended on 20 November 1962, when the US lifted its blockade.

The Cuban Missile Crisis did appear to pose a serious threat of nuclear Armageddon. President Kennedy reportedly rated the chances of nuclear war at the time as ‘between one-in-three and evens’. After all, this was a direct nuclear-armed showdown between the world’s two ideologically opposed superpowers. It came just over a year after the Soviets built the Berlin Wall, a symbol of the division of Europe and the world between capitalism and Communism. The threat of war was so real that a Soviet submarine captain apparently came close to firing a nuclear missile, in the mistaken belief that his craft was under American attack off Cuba.

Yet despite all of that, the world in 1962 was a relatively stable place. The Cold War that began after the Second World War effectively froze international relations in a stand-off. Both the US and the Soviet Union were essentially ‘status quo powers’, far more interested in preserving things as they were than trying to overthrow the other.

Since the end of the Second World War, America had pursued a policy of ‘containment’, seeking to prevent the further expansion of Soviet / Communist influence around the world. Containment was certainly not a pacifist policy – the Americans fought brutal wars first in Korea and then Vietnam in pursuit of it, and supported authoritarian anti-Communist regimes elsewhere. It did mean, however, that the US was not actively seeking direct confrontation with the Soviets.

For its part, the Soviet Union was also a status quo power. After the defeat of attempted revolutions in Germany and elsewhere in the 1920s left the Soviet Union isolated, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had abandoned the goal of international revolution in favour of defending ‘socialism in one country’. During the Cold War, Soviet policy was largely about holding the Communist bloc in Europe together and winning friends who could put pressure on the West elsewhere in the world, by linking with anti-colonial movements and newly independent nations.

This was how the Soviets came to be allies with Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Castro’s national revolutionaries, who overthrew the US-backed military dictator Batista on New Year’s Eve 1958, did not initially identify as Communists or seek Soviet support. It was after the hostile US rejected the new Castro regime’s overtures that he turned to Moscow for aid, and became a full-throated Stalinist to win the Soviets over.

As with the US policy of containment, this defensive approach did not make the Soviets pacifists. They sent tanks into Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968 to crush popular uprisings against their puppet Communist governments, and backed local anti-Western wars across Africa and Asia (including by sending Cuban troops). But the Soviet Union was not seeking war with the more powerful Americans.

Despite the fundamental political fissure in the world, the Cold War was also a time when geopolitics was largely conducted by grown-ups through diplomatic channels. While the world anxiously watched the Cuban Missile Crisis unfold live on television, both sides were also engaged in secret diplomacy, directly and through third parties, to resolve the issues. Thus, for example, Robert Kennedy’s direct threat of invasion, delivered to Khrushchev via the Soviet ambassador, was not made public at the time. Nor was the American quid pro quo agreement to withdraw its missiles from Turkey publicly announced as part of the deal. After the crisis ended, the diplomacy continued, leading to a series of agreements formally limiting the development and testing of nuclear weapons.

So, while the Cuban Missile Crisis was undoubtedly a serious affair, there was a gap between the public perception of the crisis as seen on TV and the reality of power relations behind the scenes. One US Air Force General, noting the lack of Soviet military mobilisation in response to America’s actions, would later conclude that, ‘They didn’t do a thing, they froze in place. We were never further from nuclear war than at the time of Cuba, never further.’ That seems a long way from the talk of ‘Armageddon’ that generally hangs over any mention of or comparison with the Cuban Missile Crisis today.

What might any of this tell us about the current crisis in international relations and talk of possible nuclear war over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

Unlike during the Cold War, we are no longer facing a global conflict between two ideologically divided superpowers engaged in a nuclear arms race. President Putin’s Russia, while still of course a nuclear power, is a pale imitation of the Soviet Union, which was once dubbed ‘the evil empire’. On the other side, America’s standing as unquestioned ‘leader of the free world’ has also declined compared to 60 years ago, as reflected in the divisions within the West over how to respond to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

During the Cold War era, international relations were conducted in a bipolar world, split between the two superpowers. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the final collapse of the Soviet Union two years later, international affairs briefly became seen as unipolar, with America the only superpower left standing. Today, by contrast, we are living in a more multipolar world, notably with the rise of China, where different powers and blocs jockey for position.

This might make the prospect of the sort of global conflagration threatened during the Cuban Missile Crisis seem less likely. We are no longer talking about superpowers directly threatening one another with nuclear attack.

At the same time, however, what has changed means that the world today seems a far less stable and predictable place than 60 years ago. Whereas in 1962 the West was still enjoying the postwar economic boom, the global economy today is in a far more parlous and tension-ridden state. Politically, too, the multipolar world order appears more unstable and less under anybody’s control.

Thirty years ago, when many were celebrating the fall of Communism as a historic triumph for Western capitalism, some of us predicted that Western leaders might come to miss the Berlin Wall and the sense of frozen stability it embodied for them.

This instability is both reflected and exacerbated by the failures of political leadership on all sides today. The serious leaders of the Cold War era made big public speeches, of course – but at the same time they grasped the importance of geopolitics and conducted power relations through the diplomatic channels that eventually resolved the Cuban crisis.

By contrast, today’s leaders often seem ignorant of geopolitical realities and the normal rules of international diplomacy. They appear more likely to make up foreign policy on the hoof via Twitter, rather than making considered decisions after taking counsel. They also make broad foreign-policy decisions for the narrow purposes of domestic political gain – a dangerous mix.

The lack of wise leadership in an unstable world does mean that things can more easily spin out of control, escalating a crisis such as Ukraine. We are used to being told that the biggest threat of nuclear war today is that ‘Putin is mad’, an alien creature somehow ‘not of our universe’ and capable of anything, including launching a nuclear war, on a mere whim.

The no doubt desperate Russian despot, however, is seemingly not the only world leader capable of intemperate gestures that might make conflict more likely. It was US president Biden, after all, who introduced the immediate prospect of ‘Armageddon’ into the discussion of Ukraine with his recent comparison to the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was the leader of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, who recently flew into Taiwan and promised America would defend the island against Communist China, a pointless provocation. And here in the UK, we might recall the pathetic spectacle of then foreign secretary Liz Truss’s sabre-rattling trip to Moscow shortly before the invasion of Ukraine, effectively treating a diplomatic exchange as a platform for her ambitions in the Tory party. These people can make Kennedy and Khrushchev look like Solomon-wise peacemakers by comparison.

We do live in more uncertain times when it might seem, as they used to say on the Gerry Anderson puppet show Stingray, that ‘Anything could happen in the next half hour’. For all that, most serious analysts tend to agree that the real and immediate prospect of nuclear conflict today is less obvious than it was 60 years ago – and, as noted above, even that threat was also somewhat exaggerated. (Admittedly, the fact that a high proportion of these same analysts also failed to foresee the Russian invasion of Ukraine might not fill everybody with confidence.)

But even if ‘Armageddon’ seems more unlikely, there has been another change over the past 60 years which might tend to heighten fear of nuclear war today beyond a rational level. That is the pervasive culture of fear that has settled over Western societies in recent decades.

At the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, the real if overblown fear of nuclear conflict was a more specific one based on what appeared to be happening. Today, by contrast, it might be the latest manifestation of a general, free-floating culture of fear that, as Frank Furedi has analysed in depth, can readily transfer from one panic to another. Those feelings can only be heightened by the politics of fear practised in different ways by both a ‘mad’ Putin and a blustering Biden.

We should not let the drum-beating talk of possible nuclear ‘Armageddon’ on both sides distract us from the need to support Ukraine’s fight for national self-determination. We might wish, however, for cooler heads and more considered diplomacy in these unstable times, rather than the sort of failed leadership that can turn any conflict into a Cuban Missile Crisis.

Mick Hume is a spiked columnist. The concise and abridged edition of his book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by William Collins.

Pictures by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.