Without blasphemy the West would have no free speech

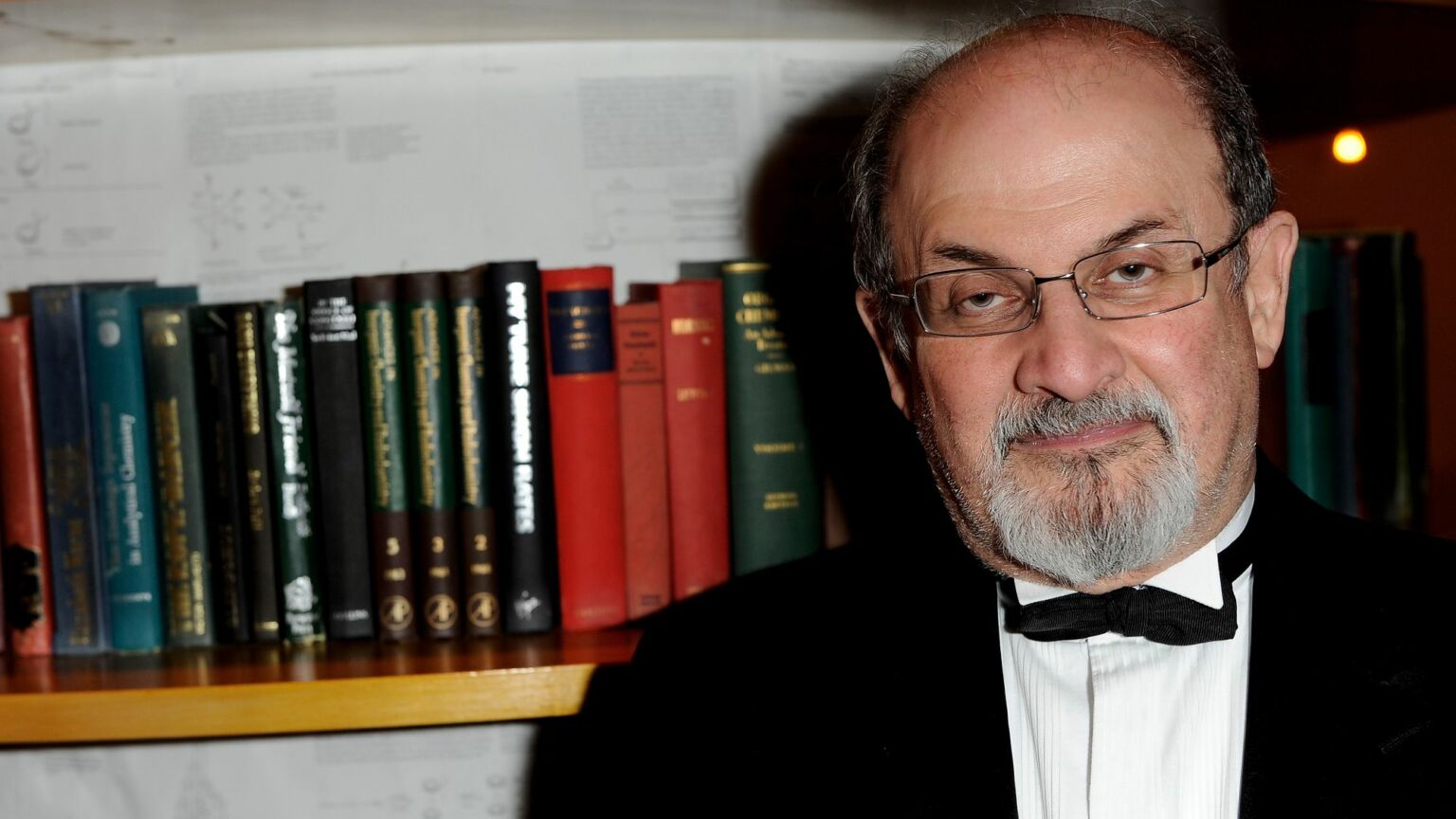

Salman Rushdie is the latest in a long line of heretical heroes.

The attempt by an apparent supporter of the Islamic regime of Iran to murder British author Salman Rushdie for the crime of ‘blasphemy’ might seem to reveal an East-West divide. But in truth battles over blasphemy have always been a central part of the struggle for free speech within the West itself.

Without those heretical heroes of history who were prepared to question prevailing orthodoxies and face down accusations of blaspheming, there would be no freedom of speech in Western societies.

Today we still have to defend the liberty to blaspheme – in modern parlance, we might call it the right to be offensive – not only against Islam and all religions, but also against the new secular restrictions on freedom of thought and speech.

‘Blasphemy’ has its origins in the Ancient Greek words for ‘injure’ and ‘speech’. The Greek ‘blasphemia’ described any impious speech or slander. Though, historically, blasphemy laws have been used in the West to punish attacks on or insults to the official Christian religion, blasphemy laws have also often been wielded in the West against critics of the established political and social order, since church and state were always closely linked.

In this, allegations of blasphemy have long been closely aligned with charges of heresy – the expression of ideas that go against the prevailing fundamental beliefs of a society, religious or otherwise.

The origins of heresy are revealing. An early Christian leader defined his own views as ‘orthodox’, from the Greek for ‘right belief’. The views of his opponents he branded as heresy, from the Greek for ‘choice of belief’.

So, the thing that has always got you labelled a heretic is the desire to choose what you believe and dissent from the authoritative dogma of the day. Otherwise known as the demand for freedom of thought and speech.

Free speech was never a gift handed down by the gods. It has had to be fought for time and again against church and state authorities which brand their critics as blasphemers and heretics. Rushdie is the latest in a long line of free-speech heroes who have suffered for their ‘blasphemous’ beliefs in the West.

It was in Ancient Athens that the idea of free speech made its first appearance in human history. Even there, however, the ruling citizens’ assembly voted to put the philosopher Socrates to death because he did not ‘believe in the gods that the city believes in’ and was ‘corrupting the youth’ with his heretical ideas.

It would be some 2,000 years later before the demand for free speech in its modern form took off, in the context of the Reformation and the Enlightenment. Today, when religion is often cast as the villain in the struggle for freedom, it is worth remembering that this struggle began as a demand for religious freedom.

In the first wave of the free-speech wars in England and across Europe, those demanding more freedom were religious heretics. Advocates of the new Protestant religions wanted to break from the control of the Church of Rome, to preach and worship in their own way, and to have a Bible printed in their own language. As punishment for such heresy, both the book and the printer could be burned. William Tyndale, who famously printed a banned English version of the Bible, was accused of ‘blasphemous heresy’, executed by strangulation and then burned at the stake in 1536.

That was barely the beginning of the battles over blasphemy and free speech in Europe. In 1600, the Italian friar-philosopher-astrologer Giordano Bruno was burnt at the stake in Rome’s Campo de Fiori, his tongue tied down to suppress his ‘wicked words’. Bruno had been condemned by the pope and the Roman Inquisition for denying the truth of core Catholic doctrines such as the virgin birth, and refusing to renounce his ‘heretical’ beliefs. His books were banned.

Then, in 1633, the Roman Inquisition infamously struck again, judging the Renaissance scientist and philosopher Galileo Galilei to be ‘vehemently suspect of heresy’ for holding the Copernican view that God’s Earth was not the centre of the universe. Galileo was forced to recant and was sentenced to lifelong house arrest, his blasphemous offending book was also removed from public view.

Nor did the Roman Catholic Church have a monopoly on persecuting free-thinking heretics. In 1656, the Jewish elders of Amsterdam expelled the great Enlightenment thinker Spinoza from the synagogue and community for committing ‘abominable heresies’ against their orthodoxies. Spinoza refused to be silenced, famously capturing the essence of the issue with his statement that, ‘In a free state, every man may think what he likes and say what he thinks’.

Back in English politics, the Crown and its supporters wielded their laws against blasphemy and heresy during the revolutionary upheavals of the mid-17th century, while free-thinking rebels such as Leveller John Lilburne demanded an end to such Crown control of the printing press as ‘expressly opposed and dangerous to the liberties of the people’.

The last person to be hanged for blasphemy in Britain was Thomas Aikenhead, a 20-year-old Scotsman, executed in Edinburgh in 1697. Young Aikenhead’s ridiculing of Jesus Christ’s miracles might sound to us like the equivalent of a modern student’s drunken outburst. But the Scottish authorities insisted on hanging him as an example to others not to speak out of order.

Even after heretics were spared the gallows, the use of blasphemy laws against critics of the system continued. John Wilkes, a heroic fighter for press freedom and democracy as well as a rogue and pornographer, was imprisoned by parliament in the 1760s for both ‘seditious libel’ and ‘blasphemous libel’. Thousands of Londoners rioted for ‘Wilkes and liberty!’ and almost lynched the then prime minister, Lord North.

Later British protests for democratic reform and giving ordinary people the vote were met with repression, culminating in the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. In response, the government of Lord Liverpool imposed new laws to suppress the protests and the radical free press, including increasing the penalty for publishing ‘blasphemous or seditious libels’ against the authorities to 14 years transportation – that is, banishment to a penal colony.

Even as democratic reforms and new freedoms were being won in the Victorian age, the attempts to outlaw heretical ideas continued. In 1859, the philosopher JS Mill published his classic case for free speech, On Liberty. In that same year, Charles Darwin finally published his magnum opus outlining the theory of evolution, On the Origin of Species. It was quickly banned as blasphemous from the library of Trinity College, Cambridge, the university where Darwin had studied.

All of that might seem a long time ago. The last successful prosecution for blasphemy in Britain was a private case, brought by the moral crusader Mary Whitehouse against Gay News in 1977, over a poem in which a Roman centurion described having post-crucifixion sex with a gay Jesus. The offences of blasphemy and blasphemous libel were finally abolished by the New Labour government in 2008.

Yet today the old offences of blasphemy and heresy have simply been redefined and updated. Hate-speech laws – now far more prevalent in the West than blasphemy laws – have effectively made thoughtcrimes of speech that can be branded racist, homophobic, transphobic or Islamophobic, among other ‘-phobias’.

Meanwhile, our culture of conformism and the fear of giving offence means that a heretical book, such as The Satanic Verses, would not be touched by many major publishers today.

In the Old Testament book of Leviticus, God tells Moses that ‘Whoever blasphemes the name of the Lord should surely be put to death. All the congregation shall stone him.’ In the modern woke equivalent, whoever blasphemes against, say, trans ideology should surely be cancelled, and all the Twitterati shall condemn him – or, more often, her.

Standing up for the freedom to question everything and say the apparently unsayable is as vital today as ever before. In the April 1989 edition of Living Marxism magazine (deceased), I wrote an editorial in response to outrage over The Satanic Verses entitled ‘Defend the right to be offensive’. It suggested that ‘blasphemy is part of the business… of all those who want to rid society of backward conventions and ideas’, and that ‘upholding the right to be offensive means rejecting any and all censorship’. Much has changed in the past 30-odd years, but some principles surely remain.

At a time when we face a new divide over freedom of expression in British and Western society, it is time for blasphemers of the world to unite in defence of heretical free speech.

Mick Hume is a spiked columnist. The concise and abridged edition of his book, Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech?, is published by William Collins.

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.