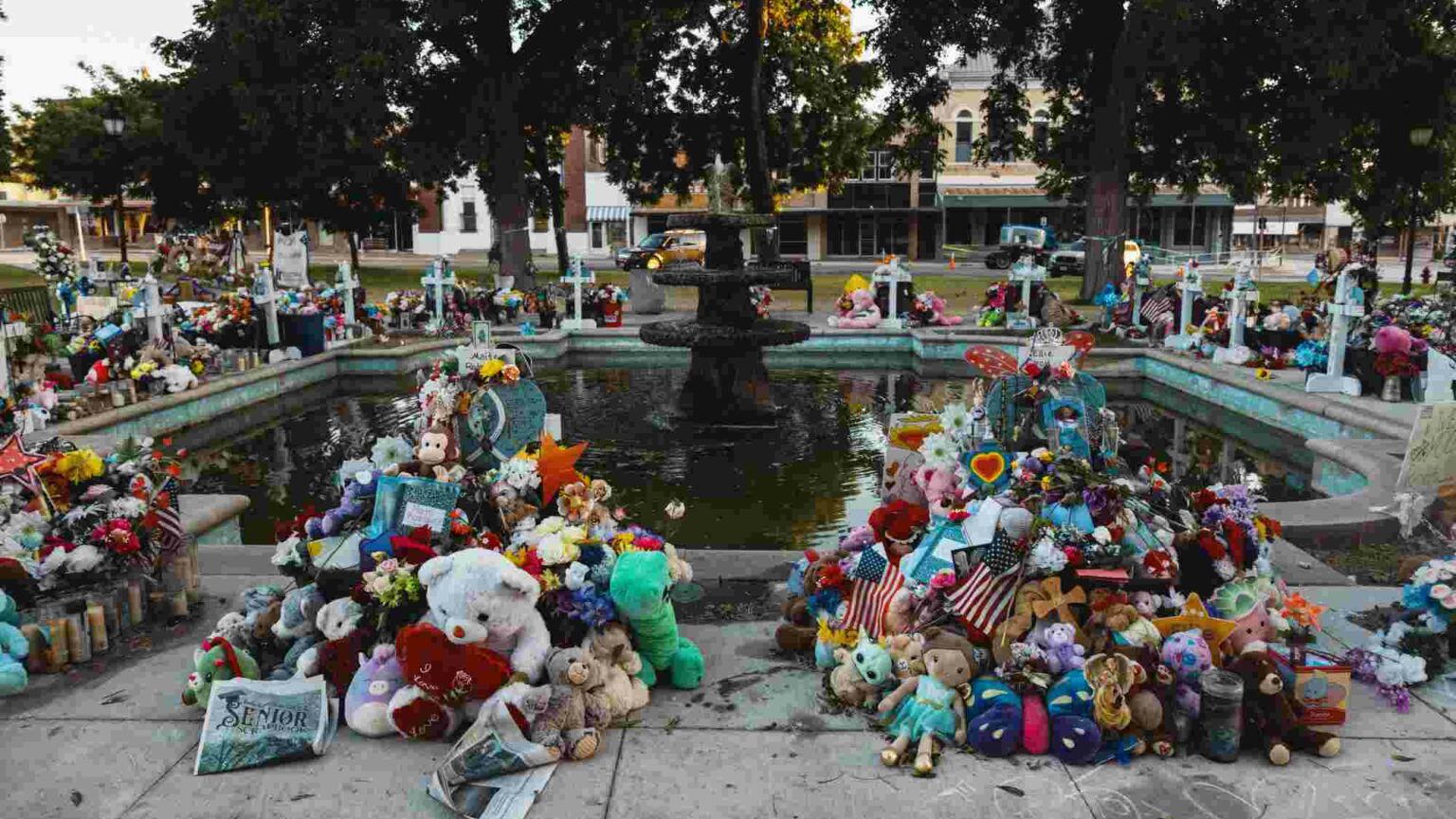

Uvalde and the deadly consequences of safetyism

The cops’ overly cautious approach made them bystanders to the mass murder of children.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

An incredible 376 officers were on the scene at the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas in May – a force larger than the garrison that defended the Alamo. All these officers failed to stop an 18-year-old gunman from murdering 19 children and two teachers. A report into the Robb Elementary School shooting commissioned by the Texas House of Representatives found no single weak point in the authorities’ response. Instead, it indicted every single one of the 23 agencies involved. Any of these could have taken control of the situation, yet none did. ‘They failed to prioritise saving the lives of innocent victims over their own safety’, is the report’s damning verdict.

All of these police forces employed a safety-first, overly cautious approach that neglected the most important qualities needed of police officers – courage, the ability to make spontaneous decisions and a determination to serve. In Uvalde, the police became bystanders to mass murder.

A culture of extreme caution also contributed to a ‘boy who cried wolf’ situation. The Robb Elementary campus seems to go into lockdown with alarming regularity. This has nothing to do with potential school shooters. Uvalde sits about 50 miles from the Mexican border, and high-speed police pursuits of migrants and human traffickers have become an increasing problem. These chases usually end with the people smuggler crashing the vehicle and the passengers fleeing in all directions. There have been almost 50 such incidents between February and May this year in Uvalde, many of them triggering lockdowns across the city. Perhaps unsurprisingly, both officers and school staff responded casually to the first lockdown alerts from the school shooting.

Of course, the ultimate blame for the horrors at Robb Elementary lies with the shooter. Most of the shots – at least 100 of a total of 142 rounds – were fired before the police arrived. It is likely that most of his victims would have died even before any responder set foot in the building. However, some of those who were badly wounded may have survived had the police properly dealt with the shooter. This would have allowed the victims to have been evacuated to safety and receive treatment more promptly.

The failures are deeply shocking. For over an hour, no one in authority seemed to want to take charge of the situation. Not one of the agencies involved comes out of the report with a shred of credibility left.

Arguably, those who come out of this worst are the Uvalde officers employed by the school district. The Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District (CISD) police had developed an active-shooter policy for dealing with exactly these incidents. In fact, the CISD was one of the few districts in Texas whose policy was judged to be ‘viable’ by the Texas School Safety Centre. On top of this, Pete Arredondo, who commanded the CISD officers during the operation, received active-shooter training from the Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training Centre at Texas University, which the FBI has recognised as ‘the national standard in active-shooter-response training’. This training instructs officers to immediately make entry and neutralise an active-shooter threat. It also teaches officers to follow the ‘Priority of Life Scale’ – whereby the lives of innocent civilians come before law enforcement. The Uvalde police did neither.

Some of the details paint an especially bleak picture. At approximately 11.37am, one officer peered into the vestibule for the two adjoining rooms where the shooter was at large. He faced gunfire. He panicked after getting grazed on the top of his head by fragments of building material. Fragments also hit another officer on the ear. They both retreated without firing a shot. The first officer, after the initial shock wore off, did then advance into the hallway. But when he called for backup, no one followed him.

No one wanted to break into the classrooms or to make the first move. Sergeant Dan Coronado of the Uvalde police was on the scene early. He requested shields and flashbangs and asked for helicopter support. Meanwhile, Chief Arredondo requested a master key to the classrooms, ‘which was a primary focus of his attention for the next 40 minutes’, according to the report. He issued a series of additional requests for equipment and support, including snipers and breaching tools. He said these were needed before police could attempt to enter the classrooms with the attacker. Lieutenant Mariano Pargas of the Uvalde police testified that ‘though nobody said it’, officers ‘were waiting for other personnel to arrive from the Department of Public Safety or BORTAC [Border Patrol Tactical Unit], with better equipment like rifle-rated shields’.

Even BORTAC, which eventually killed the gunman, exercised excessive caution. Acting commander Paul Guerrero initially attempted to pry open a door in the hallway, but then determined ‘it would… dangerously expose an officer to gunfire coming from inside the classroom’. He did not want ‘to expose or jeopardise the safety and lives of any officers by trying to pry the door open’.

The Uvalde report concludes that no one was able to stop the gunman from carrying out the deadliest school shooting in Texas history, in part because of ‘systemic failures and egregious poor decision-making’ by nearly everyone involved who was in a position to help.

The sorry tale from Uvalde could hardly be more different from events earlier this week in Greenwood, Indiana. Twenty-two-year-old Elisjsha Dicken prevented many likely deaths when he shot dead a gunman who was armed with two rifles, a Glock pistol and more than 100 rounds of ammunition. Dicken took immediate action, shooting the gunman within 15 seconds of him opening fire on a crowded mall.

Dicken encapsulates the courage, responsibility and willingness to place one’s life on the line that was so lacking in Uvalde’s police agencies that fateful day. Heroism needs individuals willing to act, to take the necessary risks to save life and limb. Heroism dies when people take a ‘safety first’ attitude.

Kevin Yuill teaches American studies at the University of Sunderland.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.