This is not a new Cold War

America yearns for a Western unity and purpose that simply no longer exists.

No sooner had Russia invaded Ukraine than American policymakers decided to turn this tragedy into an opportunity to revitalise Washington’s fading reputation as a global hegemon.

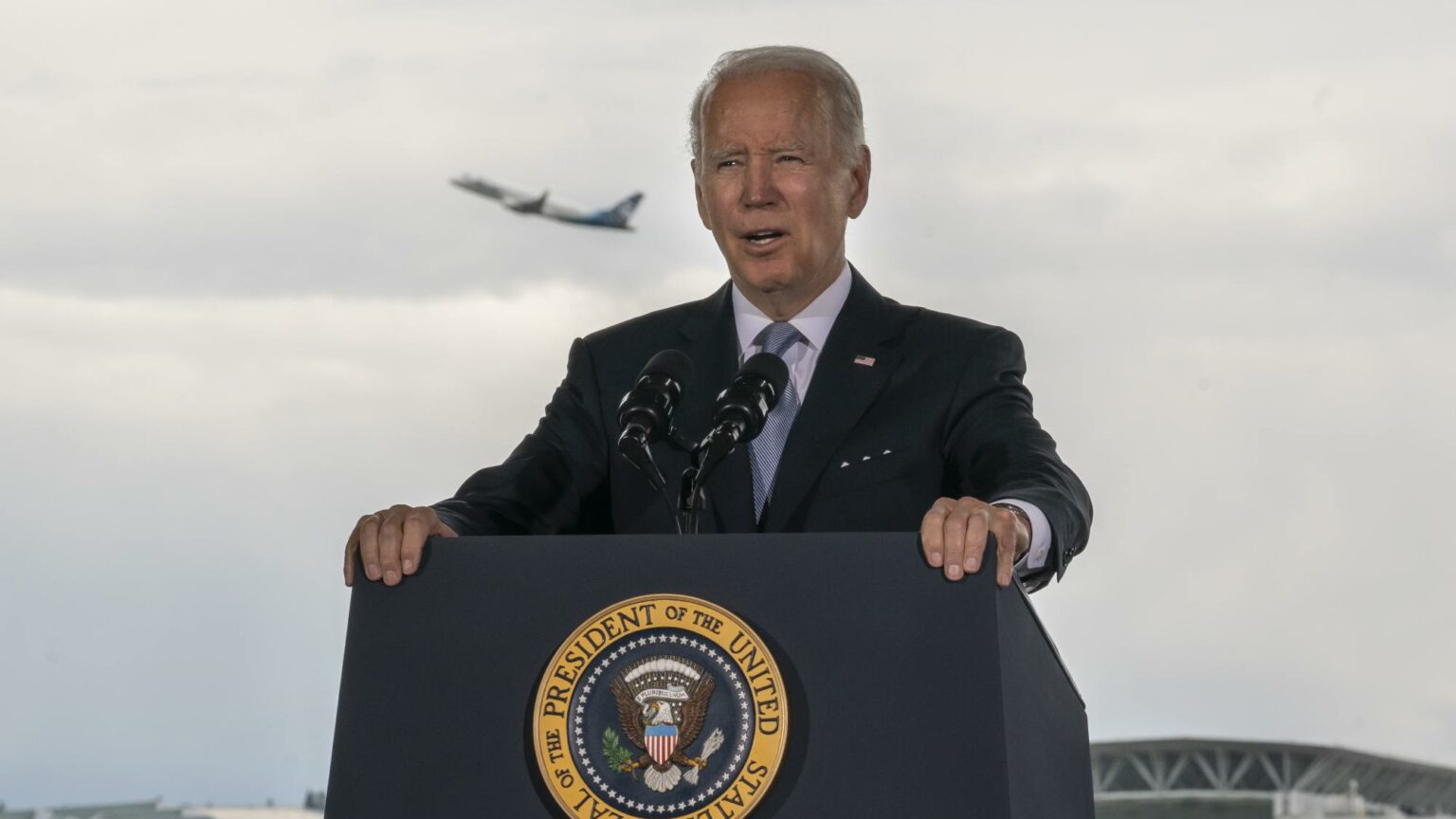

They saw the war in Ukraine as a chance to make up for America’s humiliating withdrawal from Afghanistan. A chance to remind the world of their nation’s former glory as a triumphant Cold War superpower. Hence, in a speech delivered to business leaders in March, President Biden declared: ‘There’s going to be a new world order and we have got to lead it and we have got to unite the rest of the free world in doing it.’

Indeed, US policymakers seem keen to resurrect the Cold War itself, including by advocating for a new version of the old Cold War strategy of containment – as if mobilising the Western world to isolate Russia will somehow strengthen America’s claim to global leadership. Just this weekend, for example, US defence secretary Lloyd Austin said that Washington’s goal was to see Russia so ‘weakened’ that it would no longer have the power to invade a neighbouring state.

The US’s attempt to revive the spirit of the Cold War is difficult to miss in such comments. As the New York Times put it earlier this week, the Biden administration is becoming more explicit about the future it sees – namely, ‘years of continuous contest for power and influence with Moscow that in some ways resembles what President John F Kennedy termed the “long twilight struggle” of the Cold War’.

Talk of a new Cold War is now everywhere. The ‘original Cold War’s end was a mirage’, writes Stephen Kotkin in Foreign Affairs. ‘Some experts now view the current tensions as merely a new phase in a Cold War that never ended’, reports Robin Wright in the New Yorker. ‘How quickly we have spun back up to Cold War-like hostility’, notes historian Mary Elise Sarotte in the New York Times.

But the Cold War analogy does little to illuminate current geopolitical realities. In particular, it obscures the most alarming feature of the conflict in Ukraine – that it is a hot war and not a cold one.

It is worth remembering that the Cold War itself actually suppressed military conflicts in Europe. Historian John Lewis Gaddis even characterised the Cold War period as the ‘long peace’ (1). There were good reasons for the peace and stability that prevailed in Europe during the latter half of the 20th century. The threat of nuclear annihilation deterred the US and the Soviet Union from attacking one another. And the two dominant powers subordinated conflicts within their respective alliances, such as that between France and Germany, to a larger East-West balance of power.

The global system during the decades of the Cold War was therefore relatively stable. The same cannot be said about today’s multipolar world. It has not yet established a new balance of power. For a start, there are more major players with skin in the game today than there were in the 1950s. There is China and India to consider. And the nations of Asia, the Middle East and Latin America are unlikely to accept roles as bit-part players in any new Cold War drama.

The Cold War analogy just doesn’t work for today. It is far more useful to draw a historical analogy between now and the years just before the outbreak of the First World War. This period was characterised by economic rivalry and political conflict. And it was unclear how the different sides would line up in any war to come. When war did break out in 1914, Italy was still a partner in the Triple Alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary. After initially remaining neutral, Italy then declared war against Austria-Hungary in 1915. Likewise, the US stayed out of the conflict to start with, before finally declaring war on Germany in April 1917.

If anything, the situation today is potentially even more complicated. Washington may be trying to isolate Russia, but any policy of containment will be tested by the response of China, India and other parts of the developing world. And Western powers’ current unity might not last very long, either. The often half-hearted response of Germany to demands for sanctions against Russia and arms for Ukraine shows how fragile today’s Western alliance is.

In many ways, American policymakers’ and commentators’ yearning for the Cold War is a sort of wish fulfilment. They long for a time when the idea of the West really meant something. When it enjoyed an unprecedented degree of legitimacy because, set against the Soviet Union, it looked good. It was easy to draw a sharp contrast between the Evil Empire led by Moscow and the free and democratic nations led by Washington. In short, the Cold War provided the West with a sense of moral authority.

That was then. Today, the West has little meaning as an idea. And the Western alliance, such as it is, has very little moral authority. Hence, it is divided and defensive when confronted by opponents of a Western way of life.

This is why US policymakers are drawn to the fantasy of a new Cold War – because they are nostalgic for a time of Western unity, a time when the West meant something. Their yearning, however, must not be allowed to undermine what really matters in this war: the Ukrainian people’s struggle for freedom.

Frank Furedi’s 100 Years of Identity Crisis: Culture War over Socialisation is published by De Gruyter.

(1) See ‘Explaining the Long Peace in Europe: the contributions of regional security regimes’, by JS Duffield, Review of International Studies, 20 (4), 1994

Picture by: Getty.

To enquire about republishing spiked’s content, a right to reply or to request a correction, please contact the managing editor, Viv Regan.

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.