What the war in Ukraine means for the internet

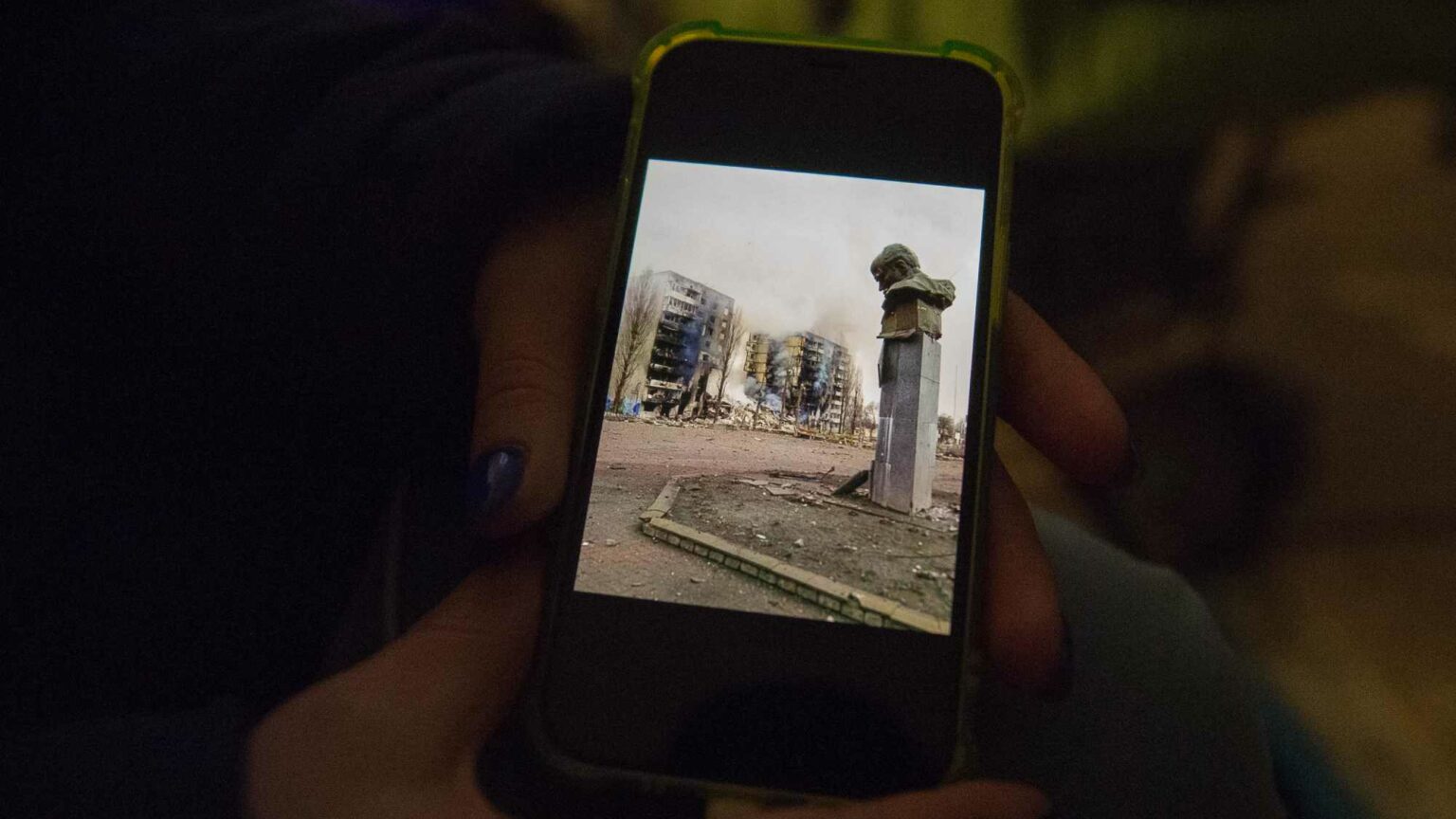

The internet has become a key weapon of the Ukrainian resistance.

Want to read spiked ad-free? Become a spiked supporter.

The war in Ukraine has shown that the internet really can survive a devastating, violent conflict.

This is no accident. Survivability was built into the very idea of an internet, from its origins in the Cold War, when the US decided that it needed to share processing power between supercomputers. It was designed precisely not to have a centralised command centre. This makes the system less vulnerable to attack because there is no single point of failure.

And we’ve seen the effectiveness of this idea in practice in Ukraine. The Russian army has subjected Ukraine’s internet to deliberate physical and cyber attacks. And yet it is still up and running.

This is both the intentional and accidental outcome of the peculiarities of Ukraine’s telecom landscape. This consists of multiple fixed, cellular and satellite networks, and it has proved remarkably resilient. The survival of Ukraine’s internet has allowed the Ukrainian people to retain critical communications capabilities and then use them to combat the Russian invaders.

The chatbot, ‘Stop Russian War’, is a good example of the way Ukrainians have used their internet. This allows users of the Telegram social-media app to upload the location and movement of Russian vehicles, and add videos and photographs in real time. This was key to the Ukrainians’ ability to defeat the Russian army’s assault on Kyiv.

Such innovation provides a useful counterpoint to the technological determinism that prevails in the West. Here, digital technologies, and the Big Tech oligarchs who own them, are deemed so powerful that they single-handedly dictate outcomes regardless of human will or desire. For instance, writing in Foreign Affairs, Ian Bremmer argues that digital powers, not nation states, will ‘reshape the global order’.

We should certainly be concerned about the power of the Big Tech oligarchs. They have gained control of the physical connections that link almost all the world’s data centres and server warehouses – the central nervous system that transforms all those computerised ones and zeros into the economic, political, social and cultural experiences of the 21st century.

Without this physical infrastructure, the digital universe we now inhabit would not exist. It relies on physically connected cables and data centres located in states and especially oceans. And Big Tech is taking ownership of an increasingly large share.

For example, in less than a decade, Microsoft, Google’s parent company Alphabet, Meta (formerly Facebook) and Amazon have become the dominant users of undersea-cable capacity. Before 2012, their share of the world’s undersea fibre-optic capacity was less than 10 per cent. Today, it is closer to 65 per cent. As the Wall Street Journal points out, Big Tech is on course over the next three years to become the primary financier and owner of the undersea internet cables connecting the wealthiest and most bandwidth-hungry countries on the shores of both the Atlantic and the Pacific.

This investment may be creating more network resilience across the globe, but it also creates grounds for bifurcation and geopolitical conflict. That’s because undersea cables and data centres are physical infrastructures subject to nation-state jurisdictions, laws and wills. Globalists might talk up a post-state world, but you can bet your bottom dollar that if Google’s undersea cable is threatened by Russian submarines, Google will fall back on the power of the US Navy to protect its interests. The internet, with its infrastructure increasingly owned by Big Tech, therefore remains captive to nation-state interests and geopolitical reality. This threatens the open-ended architecture of the internet itself.

And this is why Ukrainians’ use of the internet offers such a striking reminder of how the internet can be used when its architecture is more open. This has made it possible for Ukrainians to seize the initiative in the war. And the internet’s absence of a central command centre has made it difficult for Russia to disable it.

So the war in Ukraine has revealed, among many other things, the importance of finding ways to protect the internet’s open architecture. This is a huge political challenge, not a technological one. And it is a challenge to which the Ukrainians have risen. They have shown that it is humanity that uses technology, not the other way round.

Norman Lewis is a writer and managing director of Futures Diagnosis.

Picture by: Getty.

Who funds spiked? You do

We are funded by you. And in this era of cancel culture and advertiser boycotts, we rely on your donations more than ever. Seventy per cent of our revenue comes from our readers’ donations – the vast majority giving just £5 per month. If you make a regular donation – of £5 a month or £50 a year – you can become a and enjoy:

–Ad-free reading

–Exclusive events

–Access to our comments section

It’s the best way to keep spiked going – and growing. Thank you!

Comments

Want to join the conversation?

Only spiked supporters and patrons, who donate regularly to us, can comment on our articles.